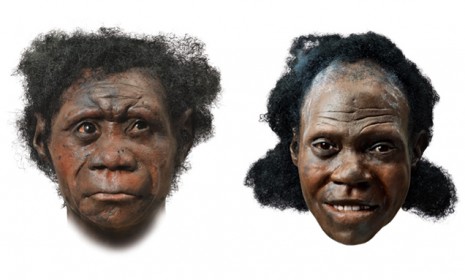

The faces of early man

The Kennis twins will change the way we see our ancestors, says Stefanie Marsh, if we're not afraid to look

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

IT IS UNLIKELY that you know what a paleoartist is. Furthermore, unless you are either an anthropologist or that rare breed of subscriber to National Geographic who actually gets around to reading the magazine, it is even less likely that you care. But you should, if only because it is a field completely ridden with interesting controversies. Take one example: The first Neanderthal remains were discovered in Germany, in the mid-19th century. For years after that, the general public assumed these creatures were thick, hairy, bull-necked folk, who walked about the Earth on bent knees; only said, "Ug"; and brandished crudely hewn stone clubs.

Now it transpires, after much more research, DNA evidence, and so on, that Neanderthals had brains bigger than ours, although with smaller frontal lobes; were not covered in fur; were probably capable of speech; and carved intricate tools, many of which survive today. The notion that they walked around on bent chimpanzee knees, it transpires, derives wholly from the fact that one of the first Neanderthal skeletons ever discovered had dodgy knees, a defect that scientists were later able to attribute to a bad case of arthritis.

And though it is scientists who make these discoveries, it is paleoartists who have, over the years, interpreted them for our benefit in the form of drawings, paintings, and three-dimensional anthropological models. I admit that my heart sank at the thought of traveling to an unremarkable city in the Netherlands to interview identical twins Alfons and Adrie Kennis. The phrase "two of the world's most accomplished paleoartists" hardly makes one want to leap onto the next flight to Arnhem. But as soon as I reach their offices, where Alfons flings open the door and begins jabbering away with his brother, I am won over.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The 44-year-old brothers tear up the stairs into a room in which shelves creak under the weight of the skulls of at least 70 mammals — living and extinct. Images of tribes from around the world, with their adornments, weather-beaten features, and missing teeth, inform all of their reconstructions. The brothers pore over coffee-table books, enthusing over, say, the particular beauty of droopy asymmetrical breasts on the tribal women of South America or the nobility of the deeply wrinkled skin of Mongolian tribesmen. I don't know how they can stay so worked up, but their obsession is genuine. They've modeled around 30 heads and six or so full bodies, and only work with casts of real skulls: the KNM-ER 1813 skull from Lake Turkana, Kenya, one of the most complete Homo habilis skulls ever found, and dated to about 1.85 million years ago; the old man of La Chapelle-aux-Saints, a Neanderthal who lived around 60,000 years ago; Wilma, the female Neanderthal built using replicas of a pelvis and cranial anatomy from Neanderthal females.

Do they consider themselves artists? "Noooo. We are no artists," says one or the other — to be honest, they sound identical on tape. Are they rich? "Nooooo," they laugh in unison. "Look," says either Alfons or Adrie, pointing at one of their reconstructions, "We used the hair of a Scottish Highlander." The hair is russet-colored and has been implanted in the head of a silicon-faced Neanderthal. What kind of Scottish men donate their hair to the paleoartistry industry? "A cow, a cow," scream the Kennises: The hair comes from Highland cattle.

The Kennises have caused some ripples in the museum world. Paleoartists are as susceptible as any of us to their own imaginations. "Artists, even scientific professors, can romanticize the past like everyone else," says Alfons. Hence, what you'll see depicted as an early example of Homo erectus, in museums, in books, or on television, is often wildly inaccurate, as influenced by fantasy or fashion as anything in a glossy magazine. You'll see prehistoric humans depicted with gleaming white teeth or smooth pale skin. "People have fantasies about what it's like to live most of your life in the outdoors," says Alfons. "It is a hard life." The Kennises don't do smooth. They don't do expressionless either. If the bones show that a prehistoric human incurred an injury to his jaw that would give him a tooth infection, this is what the Kennises will imply in the face of their reconstruction.

There are stories of nervous curators balking at the Kennises' version of Ötzi the Iceman: hunch-shouldered, wizened, with an underbite. A previous paleoartist had shown Ötzi (a mummified man, he was discovered on the Italian-Austrian border in 1991; he is 5,300 years old) as youthful and handsome, and the museum curator from Germany had hoped for something similar, preferably with blue eyes and a six-pack: a sort of Aryan folk hero. But unfortunately for the German curator, the people that most resemble prehistoric man "are tramps," say the Kennises.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We tend to glamorize our ancestors, they say. We like to think our forebears, if they are male, looked something like Arnold Schwarzenegger. If they are female, we imagine them to have long, flowing, Pocahontas hair, despite the proven absence of combs until comparatively recently. In the 1990s, the trend of paleoartists glamorizing their reconstructions reached a peak. Paleoartists were creating replicas that looked like "they just stepped out of the shower," fumes Adrie. "They made their noses too small, too pretty." They also gave them too many clothes.

Nudity is a sensitive subject even in natural history museums. When the Kennises made Wilma — a 4-foot-something Neanderthal, named after Fred Flintstone's wife — there were scientists who wanted to preserve her modesty beneath clothes. One curator told the Kennises "that Muslim children wouldn't be allowed to go into the museum because they are not allowed to see naked women." The Kennises argued that Neanderthals were more likely to be naked, and therefore caving in to religious sensitivity would be a distortion of the truth. Is there a sense that museums distort history because of their fears about how people will react? "Yah, yah!" scream the brothers in joyful and sorrowful recognition. Pendulous, asymmetrical breasts may be "beautiful" to their Dutch creators, but to a public more used to the pert, full versions "on billboards and magazines," they are ugly and obscene. "Too many people look at the past through Western glasses," says Alfons. "We think our ancestors will look like us."

WHEN THEY WERE teenagers, the twins filled up their parents' shed with the skulls of dead animals. They began to read obsessively about skulls, too. This was a godsend, they say, because they were "terrible" in school: If it hadn't been for skulls, they probably wouldn't have ever picked up a book.

Nevertheless, their prospects were not rosy, and they may well have foundered as art teachers had they not been sidetracked by the author of a children's book on prehistoric animals, who asked them to illustrate it. Being the Kennises, they decided this would be "impossible" unless they first constructed three-dimensional models of the creatures they were to draw, "to see where the light falls." Commissions from National Geographic soon followed.

In the late '90s, they persuaded an Italian scientist to lend them a cast of one of the Saccopastore skulls, fossilized hominid skulls that had been found by the Aniene River in Lazio, Italy, in 1929 and that are judged to be between 70,000 and 100,000 years old. The head they made is now on an unknown shelf somewhere in Rome. The techniques they use now are much more sophisticated, the twins say.

THE KENNISES are obsessed, eccentric, serious pioneers. One hopes that, in the end, they will win over the anxious curators and their worries about prudish visitors. A survey taken in Bolzano, Italy, where you can see the Kennises' reconstruction of Ötzi, found that most people like to think of their ancestors as good-looking, noble people with perfect skin, rather like film stars. The reality is, say the Kennises, that we looked liked homeless people. Then again, Ötzi does rather look like a film star, I thought: He's a dead ringer for Nick Nolte in Down and Out in Beverly Hills.

From the London Times. ©The Times Magazine/N.I. Syndication. Photos are from Evolution: The Human Story by Dr. Alice Roberts, published by Dorling Kindersley.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict