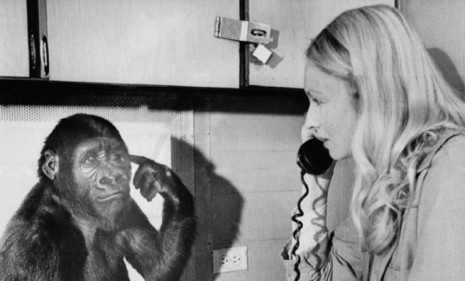

Talking to Koko the gorilla

This 40-year-old lowland gorilla, says Alex Hannaford, understands English and longs for a baby

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

MY LOCATION IS a closely guarded secret: a ranch somewhere in the Santa Cruz Mountains, several miles outside the small California town of Woodside. Its resident is something of a celebrity. She lives here with a male friend and both value their privacy, so much so that I'm asked to keep absolutely silent as I walk through a grove of towering redwoods up to a little Portakabin. Inside, I'm asked to put on a thin medical mask to cover my nose and mouth, and a pair of latex gloves. Then my guide, Lorraine, tells me to follow another dirt trail to a different outbuilding. It's here that I sit on a plastic chair and look up at an open door, separated from the outside world by a wire fence that stretches the length and width of the frame. And there she is: Koko. A 300-pound lowland gorilla, sitting staring back at me and pointing to an impressive set of teeth.

I was told beforehand not to make eye contact initially, as it can be perceived as threatening, and so I glare at the ground. But I can't help stealing brief glances at this beautiful creature. Koko, in case you're not familiar with her story, was taught American sign language when she was about a year old. Now 40, she apparently has a working vocabulary of more than 1,000 signs, and understands around 2,000 words of spoken English. Forty years on, the Gorilla Foundation's Koko project has become the longest continuous interspecies communications program of its kind anywhere.

I sign "hello," which looks like a sailor's salute, and she emits a long, throaty growl. "Don't worry, that means she likes you," comes the disembodied voice of Dr. Penny Patterson, the foundation's president and scientific director, from somewhere inside the enclosure. "It's the gorilla equivalent of a purr." Koko grins at me, then turns and signs to Dr. Patterson. "She wants to see your mouth…wait, she particularly wants to see your tongue," Dr. Patterson says, and I happily oblige, pulling my mask down, poking my tongue out, and returning the grin. Another soft, deep roar. Dr. Patterson emerges from a side door, closing it behind her, and joins me on the porch. Koko makes a sign. Dr. Patterson translates: "'Visit. Do you...' Oh, sweetheart," she says to Koko, then turns to me: "She'd like you to go inside."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Over the years Koko has inadvertently become a poster child for the gorilla conservation movement. There are several subspecies of gorillas, all in sub-Saharan Africa, and today, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, all are either endangered or critically endangered. They are threatened by disease, the illegal trade in bush meat, and loss of habitat due to logging and agricultural expansion. Attempts to educate communities where poaching is rife have largely failed; statistics about dwindling numbers of great apes don't resonate with people who can make good money from gorilla meat or body parts, or for whom the logging industry puts dinner on the table.

But some conservationists believe stories such as Koko's — of how an "inculturated" gorilla (the word researchers use for primates that have essentially had their own culture suppressed and have adopted a more human-like culture) has actually communicated with us — could be the answer. We should attempt, in other words, to win hearts rather than minds. At 40, Koko could possibly be more relevant than ever. But she's advanced in years, and the Gorilla Foundation is determined to ensure her legacy. That means allowing her to pass on her knowledge of sign language to her offspring, but despite repeated attempts to get her to mate — first with the silverback Michael and more recently with another, Ndume, her current partner — Koko's keepers' efforts have been in vain.

IT'S RARE THAT anyone gets to meet Koko up close. Most of the staff at the Gorilla Foundation have only ever been outside her enclosure. A handful of celebrities, Leonardo DiCaprio and Robin Williams included, have had the pleasure, but this was to secure publicity for the foundation. I'm told no journalist has spent as long as I will — an hour and a half — in her company. Looming above is a huge three-story enclosure that Koko can access via a hatch. Inside it is Ndume, the male silverback. We can't see each other, but I'm told he is well aware I'm here and I have to keep my voice down, as he's protective of Koko. Inside the kitchen area, I'm still separated from Koko by bars. Watched by Koko's official photographer, Gorilla Foundation co-founder Ron Cohn, I open up the bag of goodies I bought at Toys R Us and flick through a picture book on zoo animals, touching each page and holding it up to her eyes. She then points to the padlock on the door and signs for Dr. Patterson to open it. I sit cross-legged, and Koko shuffles her 300-pound frame toward me.

I'm sweating now and still trying desperately not to make eye contact. Suddenly, I feel her leathery hand softly touch mine. She pulls me gently toward her chest, wrapping her arms around me. I can smell her breath — sweet and warm, not unlike a horse's. After she releases me from her embrace, she makes another sign — fists together. "She wants you to follow — to chase her," Dr. Patterson says. Koko lightly takes my hand and places it in the bend in her arm before leading me around the small room, cluttered with soft toys and clothes. I shuffle along the floor so as not to seem threatening, but it's amazing how gentle she is.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

My wife and I had a baby daughter just three weeks before my visit, and I pull a photo out of my pocket to show her. I've learned the sign — pointing to myself and then making a rocking motion with my arms — to indicate "my baby." Incredibly, Koko takes the photo, looks at it, and kisses it. She then turns, picks up a doll from the mound of toys beside her, and holds it up to me. At one point she tugs lightly on my arm to indicate I'm to lie down beside her. Dr. Patterson says she can sense I'm nervous and does this to make people feel at ease. Another time she turns her back to me and indicates I'm to scratch it for her. She swings herself up onto a large plastic chair and Dr. Patterson turns on a video for her. It's Mary Poppins, and Koko signals that I'm to sit next to her. If my day wasn't surreal enough, it dawns on me that I'm watching Dick Van Dyke while sitting next to a gorilla. After two more hugs, Koko is coaxed away by Dr. Patterson, wielding a nut. And it's over. I stand outside on the porch again and wave good-bye, and she blows me a kiss, then puts her head up to the cage and puckers her lips. I reach out and touch them and then disappear back up the path.

THE GORILLA FOUNDATION was born in the late 1970s when Dr. Patterson was studying for a Ph.D. in developmental psychology at Stanford University. After discovering a small, undernourished baby gorilla at the San Francisco Zoo, Dr. Patterson persuaded the institution to lend her the animal and started her dissertation on the linguistic capabilities of a lowland gorilla. Two weeks into her studies, Dr. Patterson noted that Koko was able to make the signs to indicate food and drink. Project Koko, Dr. Patterson's life's work, was born. She makes it clear to me how she feels about gorillas in captivity — 40 percent of males die of heart problems before the age of 30, she tells me, something that doesn't happen in the wild — but while it was never her decision for Koko to be born in a zoo, she says, the gorilla's contribution to our understanding of her species has been immeasurable.

Dr. Patterson says Koko is extremely sophisticated in her thought processes, using not just sign language but communication cards, books, and multimedia to express herself. Some skeptics have argued that Koko does not understand the meaning behind what she is doing and simply learns to sign because she'll be rewarded. Dr. Patterson admits that in the beginning she, too, thought Koko was simply doing it to "get stuff," but the gorilla began stringing words together to describe objects she didn't know the signs for. A hairbrush, for example, became a "scratch comb"; a mask was an "eye hat"; and a ring was a "finger bracelet." From my own limited time with Koko, I could see reward wasn't her motivation. Yes, she signed to achieve goals, but these goals weren't treats: They were to get me to follow her around the room, to get me to lie down, to get me to play with her — to interact.

The idea that Koko might teach sign language to any future offspring is fascinating to researchers. Dr. Patterson says Koko's desire for a baby has evolved over the years. From the age of about 6 she was caring for dolls, and her maternal instincts progressed to living things: a rabbit "wandering around Stanford — obviously a lab escapee" — and then a kitten that Koko named All Ball, eventually the subject of a children's book by Dr. Patterson.

"She was very gentle and careful with All Ball," says Dr. Patterson. "She wanted to nurture it." But a few months after All Ball came into Koko's life, the cat escaped from her enclosure and was run over by a car. Dr. Patterson says that when Koko found out, she signed "bad, sad, bad" and "frown, cry, frown." Recently, Dr. Patterson says, Koko has shown no interest in visiting kittens — an indication, she believes, that she is now after the real thing. Through pictures and signs, Koko has indicated that she'd like to raise a child in a group situation. "A mother gorilla and baby in isolation aren't healthy. Zoos have discovered this," Dr. Patterson says. "It takes a village to raise a baby gorilla — just like humans." The ideal scenario is that a zoo or wildlife park loans the Gorilla Foundation a couple of females. Ndume would then impregnate one of them and the three mothers, Koko included, would raise the baby in a group.

The book Koko's Kitten was published 24 years ago, but now Patterson aims to distribute it in areas in Africa where gorillas are threatened — to teach children there how a great ape can love and care for an animal of another species. We've also learned that great apes, like humans, have the capacity for empathy, says Dr. Patterson. "Their politics work like our politics," she says. "If you're not nice, you're out of the group."

By Alex Hannaford. A longer version of this article appeared in the London Telegraph. ©Telegraph Media Group Limited 2011/Alex Hannaford.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day