Exhibit of the week: Avant-Garde Art in Everyday Life

On exhibit at The Art Institute of Chicago is some 300 art objects—including home goods, political posters, and book covers—designed by European avant-garde artists of the 1920s.

Art Institute of Chicago

Through Oct. 9

With the right teacup design, you can change the world, said Rachel Wolff in The Wall Street Journal. Or so thought Europe’s 1920s avant-garde, many of whom felt that the best way to get people thinking modern was to fill their homes with stylish, affordable objects that embodied the movement’s progressive principles. The Art Institute is offering a fascinating look at this innocent “moment of optimism and artistic innovation,” with some 300 art objects—including home goods, political posters, and book covers—made by six of the movement’s leading lights. Some of the “sleek though largely unadorned” dinnerware on display may look a little plain today, but at the time it was revolutionary. Clean-lined and thoroughly 20th-century, it represented a dramatic break from the froufrou Victorian look that had been in vogue until that moment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In short, these designers were more interested in form than in decoration, said Janina Ciezadlo in Newcity Art. With his popular line of china, Czech designer Ladislav Sutnar enacted a “restrained play of spherical volumes,” while Piet Zwart pared his teacups down to squat apple-green cylinders sitting in hexagonal saucers. A similar repudiation of tradition drove the graphic design of the period, as artists bandied about bold fonts and striking imagery that looked as radical as the messages being conveyed. “The exhibition is more than worth the trip if only to see John Heartfield’s photomontage posters and covers for the anti-fascist Workers’ Illustrated Magazine.” Also fabulous: Gustav Klutsis’s postcards for the 1928 Spartakiad, which “evoke the dynamism and heroics of sport.” Each of Klutsis’s images is a controlled collision of strong diagonals, and that energy is amplified by the artist’s use of photographic images of athletes in action, many of them shown pressing right up against the edges of the paper.

What’s most striking is how modern these works still look today, said Terry Loncaric in the Gary, Ind., Post-Tribune. There is, throughout the show, “an undercurrent of bold experimentation” that feels contemporary and fresh. Yet there’s also something strangely familiar in the way these artists cavalierly cut and pasted various elements of graphic design—including words and photos—to produce what they hoped would be “compelling cultural and political statements.” Although the artists couldn’t have known it at the time, this fast-and-loose approach to content foreshadowed the free-for-all creative spirit of the Internet. For a group of future-minded pioneers hoping to reshape the world, that’s not too shabby a legacy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

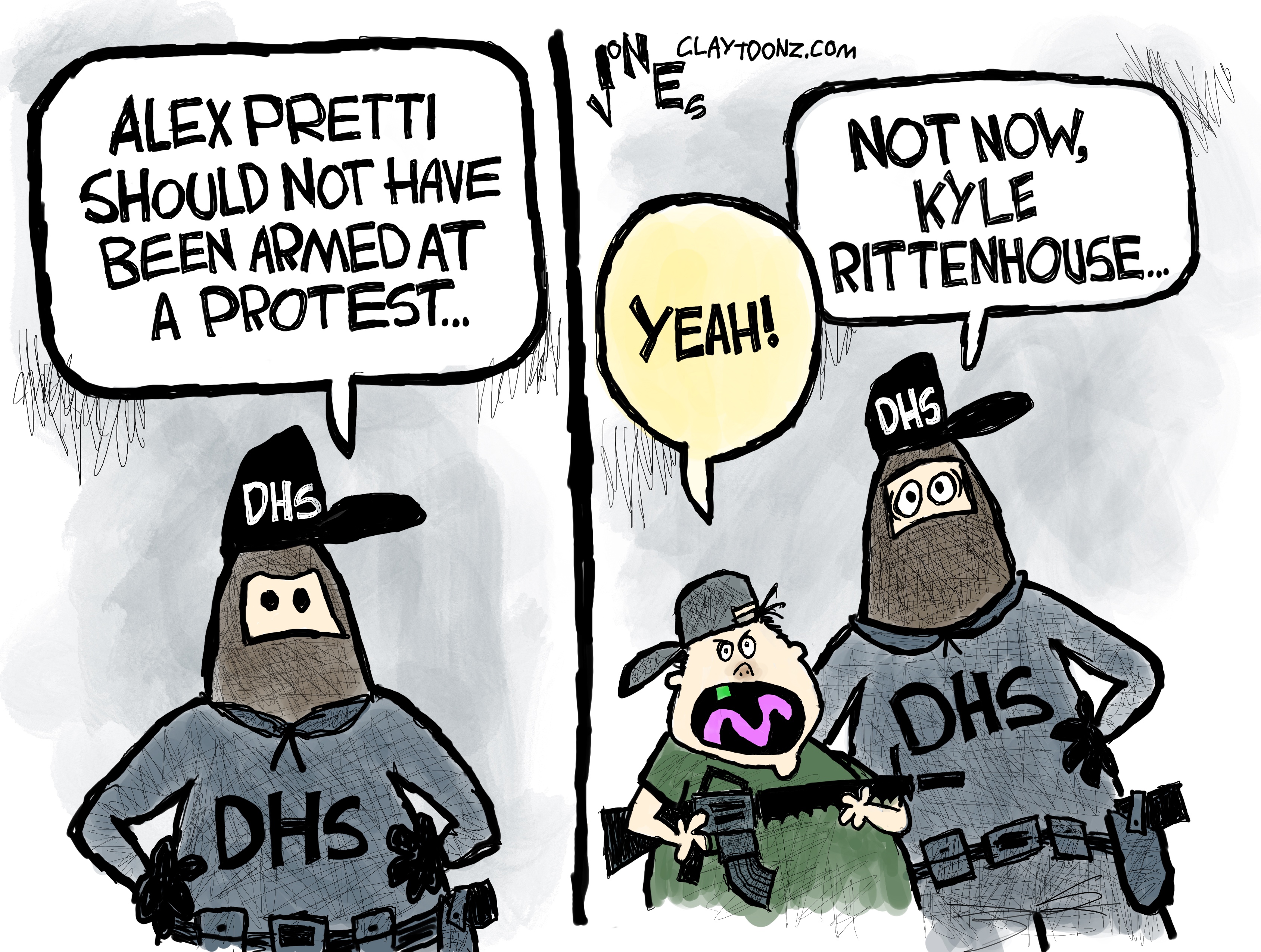

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aid

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aidIn the Spotlight AI has enabled the scam to spread into community colleges around the country

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities