Why does the US want to put nuclear reactors on the moon?

The plans come as NASA is facing significant budget cuts

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

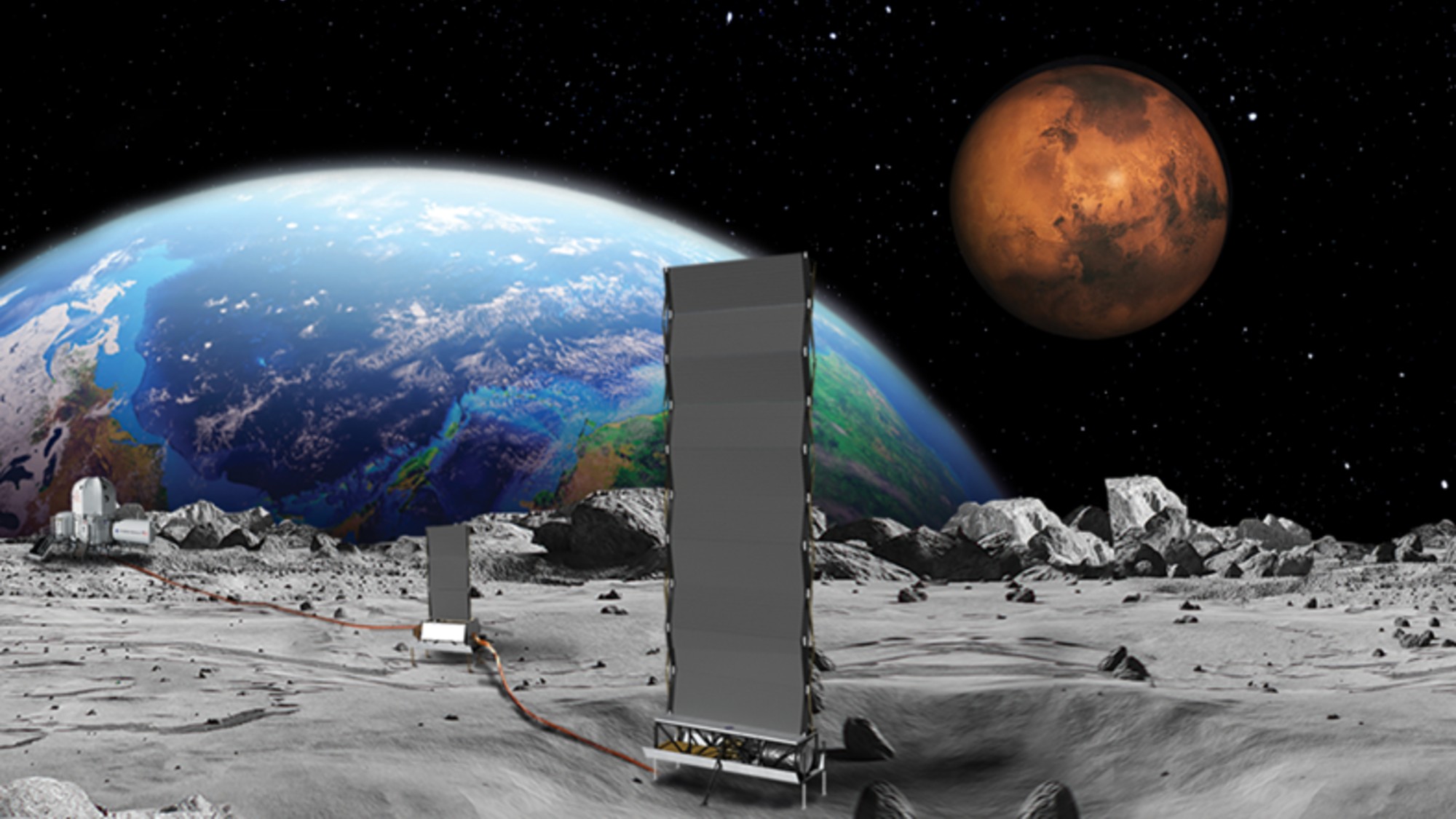

If you want to know where the next nuclear reactor is being built, you may have to look up at the stars. Transportation Secretary and interim NASA Administrator Sean Duffy is moving forward with a plan to construct nuclear reactors on the moon in the hopes of expanding American influence in outer space. But this may be easier said than done, thanks to the government itself, as NASA is facing significant budget cuts courtesy of the Trump administration. This could make the agency's nuclear goals difficult.

What did the commentators say?

The White House claims that the nuclear reactor project "could help accelerate U.S. efforts to reach the moon and Mars — a goal that China is also pursuing," and the "plans align with the Trump administration's focus on crewed spaceflight," said Politico, which first reported the news. It is "about winning the second space race," a NASA official told the outlet. "Let's start to deploy our technology, to move to actually make this a reality," Duffy said in a press conference.

Nuclear technology on the moon would "transform the ability of humanity to travel and live in the solar system," said The New York Times. A single lunar day is the equivalent of four weeks on Earth and cycles between two weeks of sunshine and two weeks of darkness. This "harsh cycle makes it difficult for a spacecraft or a moon base to survive with just solar panels and batteries," making nuclear power an attractive option. A "reactor would be useful for long-term stays on the moon, especially during the two-week-long nights."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Putting a "reactor on the lunar surface to help power moon exploration efforts would keep the United States ahead of China and Russia," said CNN. Both of these nations have announced similar nuclear projects, and if either of these countries managed to "achieve this feat first, it could declare a 'keep-out zone'" that "would effectively hold the U.S. back from its goal of establishing a presence on the lunar surface."

The plans for a lunar nuclear reactor aren't entirely new, as NASA has been considering them for a long time. But the administration's directive could "accelerate NASA's long-simmering — and, to date, largely fruitless — efforts to develop nuclear reactors to support space science and exploration," said Scientific American.

What next?

Duffy said NASA wants a 100-kilowatt reactor on the moon by 2030. However, questions remain about its viability, especially given recent actions by the Trump administration. While the White House has "proposed a budget that would increase human spaceflight funds," at the same time it "advocates for major slashes to other programs — including a nearly 50% cut for science missions," said Politico.

NASA had "previously funded research into a 40-kilowatt reactor for use on the moon," but this research is unlikely to move forward given current budget cuts by the Trump administration. The agency also "plans to award at least two companies a contract within six months of the agency's request for proposals," meaning the nuclear reactor initiative could move forward regardless.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is "on-brand for America," said astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson to "CBS Mornings." What is "not on-brand is to cut science programs, not only in NASA but across the board, and then say, 'We want to excel in this one spot.'" For the U.S. "to say, 'Let's cherry-pick where we want to show the world where we're the best,' you can't really do that."

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interview

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interviewSpeed Read The late night host said CBS pulled his interview with Democratic Texas state representative James Talarico over new FCC rules about political interviews

-

The Week contest: AI bellyaching

The Week contest: AI bellyachingPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

Nasa’s new dark matter map

Nasa’s new dark matter mapUnder the Radar High-resolution images may help scientists understand the ‘gravitational scaffolding into which everything else falls and is built into galaxies’

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanrooms

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanroomsUnder the radar The bacteria could contaminate space

-

Artemis II: back to the Moon

Artemis II: back to the MoonThe Explainer Four astronauts will soon be blasting off into deep space – the first to do so in half a century

-

The mysterious origin of a lemon-shaped exoplanet

The mysterious origin of a lemon-shaped exoplanetUnder the radar It may be made from a former star

-

Blue Origin launches Mars probes in NASA debut

Blue Origin launches Mars probes in NASA debutSpeed Read The New Glenn rocket is carrying small twin spacecraft toward Mars as part of NASA’s Escapade mission

-

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusion

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusionThe Explainer Harnessing the reaction that powers the stars could offer a potentially unlimited source of carbon-free energy, and the race is hotting up