Health & Science

A revelation beneath the Antarctic ice; Elephants grasp teamwork; Parenthood and happiness; A pathway to lost memories?

A revelation beneath the Antarctic ice

Antarctica’s vast ice sheets grow as the result of snow that piles up on top and freezes. Or so scientists always thought. Surprising new research has found that the sheets also grow from the bottom, as the result of layers of water that freeze and become part of the ice. “It’s jaw-dropping,” study co-author Robin Bell, a professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, tells BBCNews.com. “The first time I showed the data to colleagues, there was an audible gasp.” Using radar images taken from planes over the ice-encased Gamburtsev Mountains, her team spotted enormous subsurface plumes of ice, created when water flowing between the ice sheets and the rock surface froze. That previously unknown process can account for more than half the depth of the ice sheets, which are 2 miles thick in some places. Scientists have long viewed the ice sheets essentially as layer cakes of compressed snowfall, and figured the water beneath them functioned only as a lubricant that allowed them to move, much as glaciers do. The new discovery could be “critical” to predicting how the world’s ice sheets respond to global warming, researchers say. The stakes are high: All told, the ice sheets hold enough water to raise global sea levels by 200 feet.

Elephants grasp teamwork

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Wild elephants work together to care for their young, help injured members of their herd, and even mourn their dead. Are they doing so out of pure reflex or because they understand the advantages of common action? To find out, Cambridge University scientists put 12 pachyderms from the Thai Elephant Conservation Center in pairs and gave each partner one end of a rope; the middle of the rope was attached by pulleys to food that was out of reach. All the elephants quickly learned that, to retrieve the snack, both ends had to be tugged at the same time. But beyond that, they demonstrated an understanding of their partners’ role. When scientists sent an elephant to the apparatus alone, she would wait up to 45 seconds for help to arrive—a long time by the standards of a hungry elephant. And if no partner came, or if only one end of the rope was available, the elephants often didn’t bother trying at all. Lead author Joshua Plotnik tells ScienceNews.com that the findings put elephants “on par with chimps” in social awareness. “I was surprised how quickly they learned,” he says. “Clearly elephants fit in the top echelon of animal intelligence.”

Parenthood and happiness

Parents tend to say that their children bring them joy, but research consistently shows that raising kids causes marital stress and other varieties of unhappiness. A new long-range study may explain that contradiction, LiveScience.com reports. Demographers from Germany’s Max Planck Institute surveyed 200,000 men and women in 86 countries and found that young parents with young children were generally unhappier than their childless peers, while older parents with older children were happier. Children, in other words, “may be a long-term investment in happiness,” says study author Mikko Myrskylä. Globally, the contentment of couples under 30 decreased with the birth of their firstborn, and dropped further with each subsequent child they had. Conversely, parents over 50, no matter how many kids they’d raised, were happier than their childless counterparts. The trend was less pronounced in countries with highly developed welfare systems, like Switzerland, where parents and nonparents tended to be equally happy at any age. Myrskylä and his colleagues believe their findings suggest that the expense, anxiety, and lost sleep brought on by young children overshadow the positive aspects of parenthood—until those kids grow up to become a source of financial and emotional support.

A pathway to lost memories?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Raising hopes that dementia could one day be reversed, scientists have discovered a way to re-create key neurons that die off in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. After testing millions of embryonic stem cells for six years, researchers at Northwestern University have unlocked the genetic code that allows them to transform stem and skin cells into basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. When the disease destroys these neurons, patients lose access to their memories, but they don’t actually lose the memories themselves. Researchers implanted lab-generated BFC cells into mice and observed that they build memory pathways just as normal neurons do. That opens the prospect that transplanting such cells into the brains of human Alzheimer’s patients could restore their mental function. The research “could have an impact in the next couple of years,” William Thies, chief medical and scientific officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, tells HealthDay.com, as the ability to create BFC cells allows researchers “to much more rapidly test new therapies.”

-

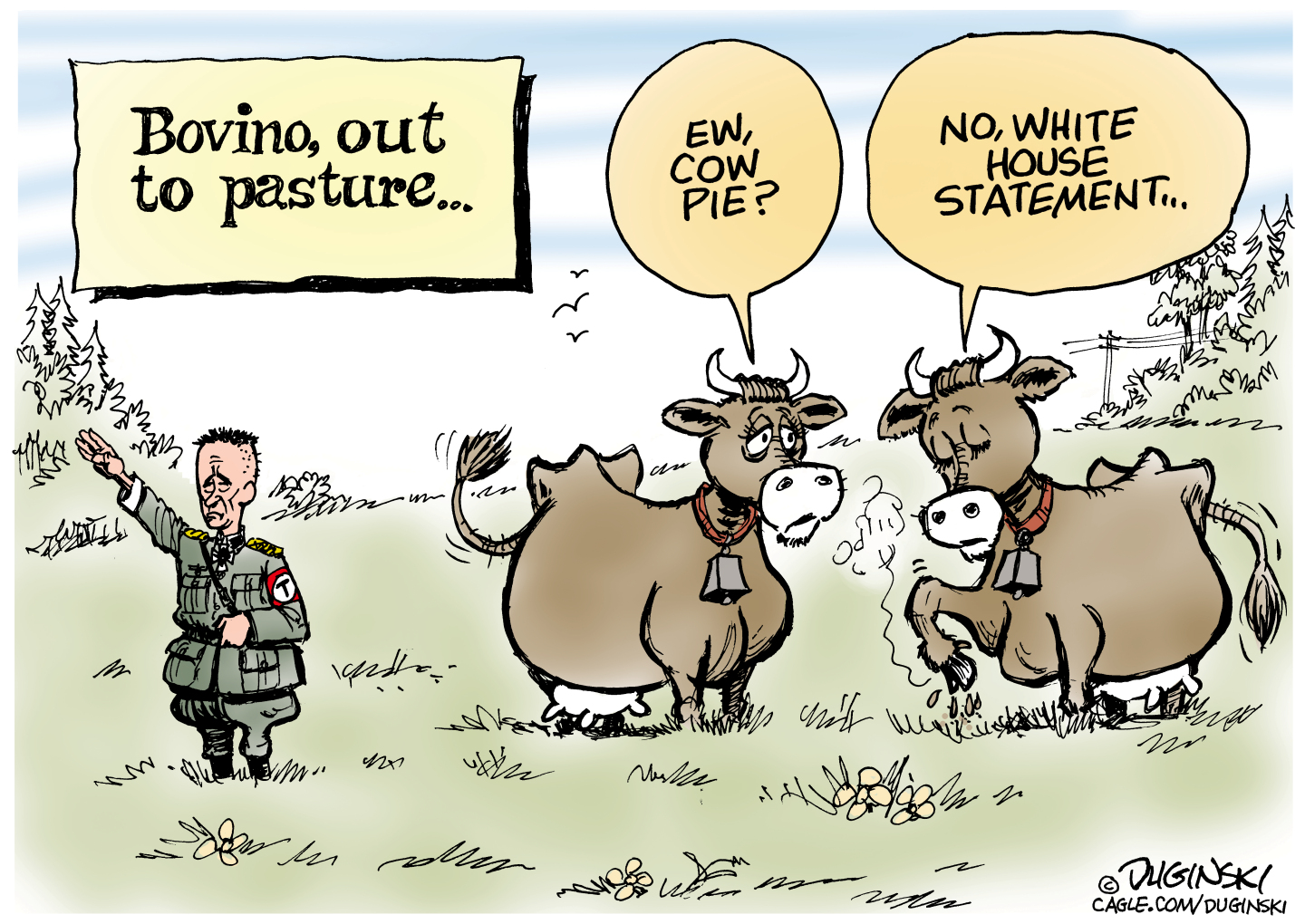

5 redundant cartoons about Greg Bovino's walking papers

5 redundant cartoons about Greg Bovino's walking papersCartoons Artists take on Bovino versus bovine, a new job description, and more

-

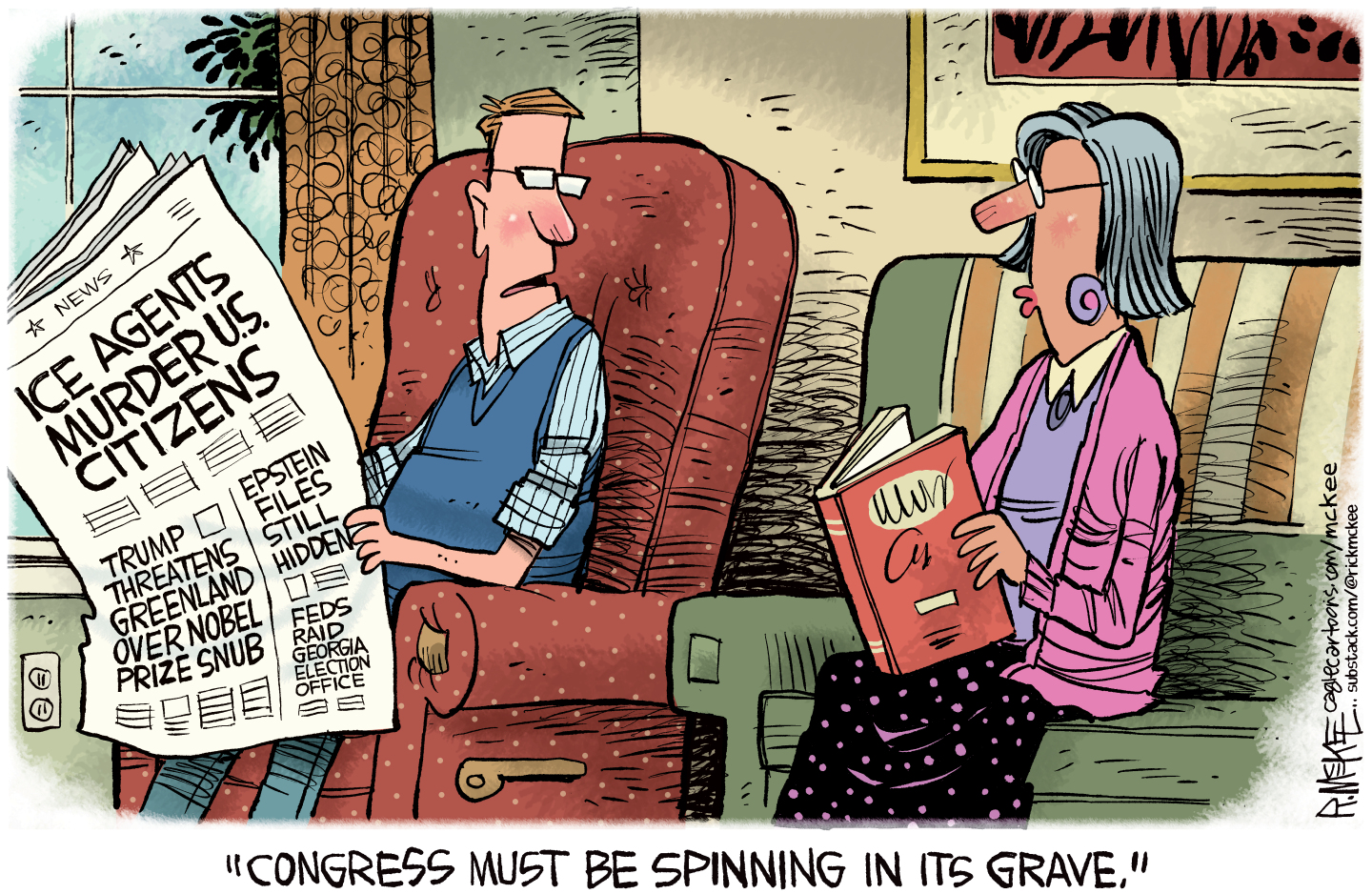

31 political cartoons for January 2026

31 political cartoons for January 2026Cartoons Editorial cartoonists take on Donald Trump, ICE, the World Economic Forum in Davos, Greenland and more

-

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more