The mystery of falling crime rates

Despite widespread economic hardship, the nation’s crime rate has continued to fall. Why?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What do crime statistics show?

The historic drop in crime that began in the early 1990s continues. Last year, violent crime fell an impressive 5.5 percent nationwide, marking the third straight year of decline after an even longer-lasting drop briefly lost momentum earlier in the decade. The cumulative falloff is truly remarkable: Murders slipped 7 percent last year, to 15,100—nearly 45 percent below the 1991 peak. And the declines involve nearly every category of crime, in communities big and small. Property crime last year was down 4.9 percent; robbery, 8.1 percent; and auto theft, 17.2 percent. Even struggling Detroit enjoyed a 2.4 percent drop in violent crime. For many experts, the big surprise was that crime continued to fall even as the national economy was tanking. “This is a real break in past patterns,” says criminologist Richard Rosenfeld.

What explains the decline?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Nobody is sure, though at least some credit must go to improved policing methods that began with New York City in the 1990s. The city’s police commissioner, William Bratton, adopted a strategy espoused by criminologist George L. Kelling known as the “broken windows theory”—the idea that street cops could suppress serious crime by paying attention to minor offenses, such as graffiti or vandalized windows, that create an anything-goes, Wild West atmosphere. New York City also adopted a “zero-tolerance’’ policy that got squeegee men, the homeless, and petty criminals off the streets, and sought to take illegal guns out of circulation. Finally, the new strategy embraced the idea that most robberies, assaults, rapes, and murders are caused by a small number of hard-core criminals who victimize citizens again and again.

What do police do about those criminals?

Identify them, track them down, and keep them in jail. In New York’s policing model, the commissioner’s office mapped crime patterns daily and demanded that precinct-level commanders take quick steps to locate the repeat offenders causing most of the crime. Using those patterns, police nationwide now target the repeat offenders in every neighborhood and seek to get them off the street. The concept even works for small-town vandals. Then again, major drops in crime also have occurred in places that have not adopted such reforms, which suggests they can’t be the only explanation for the crime decrease.

What else could explain it?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

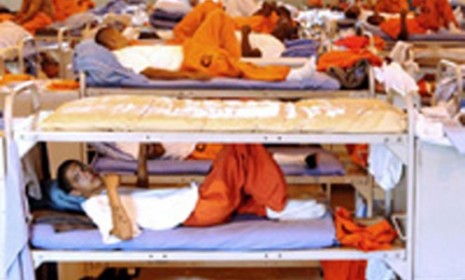

The exploding prison population. Since the 1980s, federal, state, and local governments have enacted harsher prison terms for major and minor crimes alike. As a result, the U.S.’s incarceration rate is four times the world average, with a record 2.3 million Americans now behind bars. Tough-on-crime legislators note that somebody who’s locked up can’t hurt society at large, and they see a direct link between the get-tough approach and the drop in crime. But statistics show that it’s not that simple. States in which prison populations grew most dramatically in the 1990s actually lagged behind the rest of the country in cutting crime. And the growth in the number of people behind bars slowed considerably last year, yet crime dropped significantly anyway. With neither improved policing nor longer sentences fully explaining the crime drop, experts have looked for explanations outside the criminal-justice system. And they’ve come up with some fairly wild theories.

What factors do they identify?

Lead poisoning and abortion, to name two. One intriguing hypothesis about why Americans were so prone to violence in the 1980s was that many young people were suffering the effects of lead poisoning. The link between lead poisoning and aggressive or impulsive behavior is well established. And peaks in children’s exposure to the toxic metal, first due to lead paint and then to leaded gasoline, were followed roughly 20 years later by two of the 20th century’s worst crime eras. Under this theory, the phasing out of lead paint and leaded gasoline explains the reduction in crime. As for abortion, Steven Levitt, co-author of the 2005 best-seller Freakonomics, argues provocatively that the legalization of abortion in 1973 reduced the number of unwanted babies being born into troubled homes, and thus reduced the number of troubled teenagers who reached their crime-prone years two decades later. Still, he hasn’t been able to explain why crime peaked when the leading edge of that cohort hit age 18, and then fell off.

So can any theory explain the recent crime drop?

A confluence of several factors is likely responsible, but perhaps the strangest theory yet is that the recent recession caused the recent drop in crime. Some sociologists are offering the idea that because millions of people lost their jobs over the past two years, there were far more people sitting at home in the middle of the day. That would reduce burglaries, and muggers might slack off, too, because they would assume that their potential victims have empty pockets. But, say these same criminologists, beware the day when unemployment benefits run out and desperation rises. Indeed, some cities have already seen violent crime jump in 2010. If there’s a link between economic hard times and crime, warns Northeastern University’s James Alan Fox, it may kick in after a short delay—and “the good news we see today could evaporate.”

Still nothing to brag about

Despite the recent decline in crime, the U.S. is still the most violent of affluent democracies. The annual U.S. murder rate of five per 100,000 people is down from 9.8 in 1991, but still twice that of, say, France. Historian Randolph Roth recently surveyed U.S. homicides over the centuries and concluded that violence rises whenever citizens develop a strong distrust of the government and feel powerless over their own lives. Murders soared just before the Civil War, when anti-Washington fever reached its peak. Crime has never settled back to European levels. The homicide rate among white Americans, Roth notes, soared again in the late 1970s, when “malaise’’ was widespread. “Our high homicide rate started when we lost faith in ourselves,” he says, “and each other.” With polls showing a growing distrust in government, that’s a worrisome thought.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown