Susan Rothenberg: Moving in Place

The 25 paintings at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth show how Rothenberg developed her unique aesthetic.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

Fort Worth, Texas

Through Jan. 3

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the early 1970s, when Susan Rothenberg was a young painter living in New York, minimalism was the rage and “figuration was all but extinct,” said Kimberly Straub in Vogue.com. So how did Rothenberg make a name for herself? She “decided to make huge paintings of horses.” Rothenberg didn’t particularly like horses or have much knowledge of them. “She based her decision solely on finding a recognizable image she could deconstruct” in expressionistic paintings that pulse with kinetic energy. This “tight-knit selection of 25 canvases” from throughout her career shows how the artist forged her unique aesthetic.

Horses turned out to be the perfect subject with which to make an artistic statement, said Gaile Robinson in The Dallas Morning News. “Even in a simple line form, they speak of mass and motion,” and they have deep roots in art history. Yet Rothenberg left the motif behind when she moved to “the wilds of New Mexico” in 1990. Her new surroundings revealed a darker side of the animal world. “Fearful encounters such as The Chase and Dogs Killing Rabbit became her subject matter, and her canvases began to swirl with frenzied action.” More recently, she abandoned realistic images entirely, producing paintings that “show disembodied arms and hands dancing about the canvas.” None of Rothenberg’s paintings is perfect. “Her draftsmanship leaves something to be desired,” but she compensates with exuberant brush strokes that boil each scene down to its essentials. Three decades after Rothenberg first went her lonely way, figuration is back “in vogue,” and her own early art is a big reason why.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

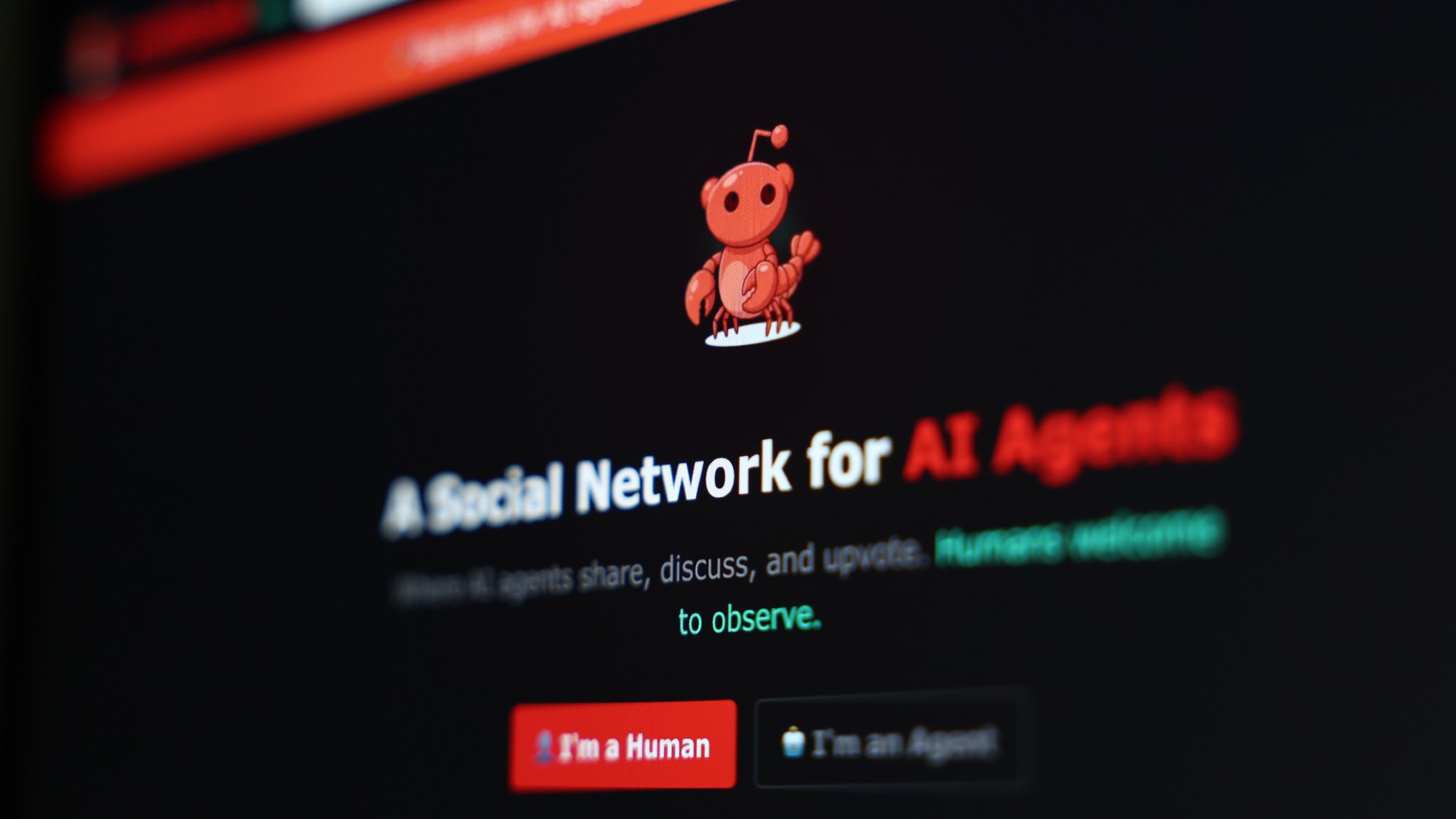

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg

-

If/Then

feature Tony-winning Idina Menzel “looks and sounds sensational” in a role tailored to her talents.

-

Rocky

feature It’s a wonder that this Rocky ever reaches the top of the steps.

-

Love and Information

feature Leave it to Caryl Churchill to create a play that “so ingeniously mirrors our age of the splintered attention span.”

-

The Bridges of Madison County

feature Jason Robert Brown’s “richly melodic” score is “one of Broadway’s best in the last decade.”

-

Outside Mullingar

feature John Patrick Shanley’s “charmer of a play” isn’t for cynics.

-

The Night Alive

feature Conor McPherson “has a singular gift for making the ordinary glow with an extra dimension.”

-

No Man’s Land

feature The futility of all conversation has been, paradoxically, the subject of “some of the best dialogue ever written.”

-

The Commons of Pensacola

feature Stage and screen actress Amanda Peet's playwriting debut is a “witty and affecting” domestic drama.