End times for Milton Friedman?

After World War II, laissez-faire economists had a big intellectual problem: the Great Depression. How could you argue for dismantling the post-WW II social insurance states and returning to the small-government laissez-faire of the past when that past contained the Great Depression? Some argued that the real problem was that the laissez of the past had not been faire enough: that everyone since Lord Salisbury and William McKinley had been too pinko and too interventionist, and thus the Great Depression was in no way the fault of believers in the free-market economy. This was not terribly convincing. So advocates of a smaller government sector needed another, more convincing argument.

It was provided by Milton Friedman.

Friedman proposed that with one minor, technocratic adjustment a largely unregulated free-market would work just fine. That adjustment? The government had to control the "money supply" and keep it growing at a steady, constant rate--no matter what. Since money was what people used to pay for their spending, a smoothly-growing money supply meant a smoothly-growing flow of spending and, hence, no depressions, Great or otherwise. In Friedman's view, if the task of monetary stabilization could be accomplished via technocratic manipulations by a non-political central bank, there would be no need for much of the apparatus of the post-World War II social insurance state.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the 1950s Friedman's doctrines were considered way out there. But his Keynesian adversaries overreached, and claimed that clever governments could maintain price stability and a high-pressure economy with "full" (rather than merely "normal") employment. By the 1970s, it was clear they were wrong. Since then, advocates of expanded social democracy have been on the retreat more often than on the advance. By the 1990s, even left-of-center politicians had come to respect central bankers' mastery of the money supply, giving them a wide berth.

The power of Friedman’s theory was, in part, rhetorical. "Keep the money supply growing smoothly" sounds like it means to keep the presses in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing rolling at a constant pace, printing out a steady flow of pictures of George Washington. But that is not how "money supply" actually works. In economic reality, "money supply" means not just cash money but also credit entries the Federal Reserve has made in commercial banks' accounts at the Fed; plus all the credit entries commercial banks have made in households' and businesses' checking accounts; plus savings account balances; plus (usually) money market mutual-fund balances; plus (sometimes) trade credit and the ceilings between credit card limits and consumers' current balances.

No central banker controls all these vast and varied sluices of the money supply – at least not in economic reality. When banks and businesses and households get scared and cautious and feel poor, they take steps to shrink the economic reality that is the "money supply." Businesses extend less trade credit. Credit card companies cut off cards and reduce ceilings. Banks call in loans and then take no steps to replace the deposits extinguished by the loan pay-downs. Without a single bureaucrat making a single decision to slow down a single printing press, the money supply shrinks—disastrously in episodes like the Great Depression. Thus in emergencies, to say that all the central bank has to do is to keep the money supply growing smoothly is very like saying that all the captain of the Titanic has to do is to keep the deck of the ship level.

For the past eighteen months the collective central banks of the world have been trying as hard as they can to keep the deck of the ship level. Traditionally, central banks boost the money supply by buying government bonds from the Treasury for cash. Buying government bonds for cash cuts the supply of bonds the private sector can acquire, boosting their price while lowering interest rates, making businesses more eager to spend to expand and making asset holders feel richer and thus more eager to spend to consume.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The central banks and finance ministries of the world have purchased so many government bonds for cash that they have pushed the prices of short-term government bonds up as high as they can possibly go. With interest rates practically zero, there is no extra interest return to be gained in the short run from bonds. Yet it has not been enough.

So increasingly over the past year, the central ministries of the globe have taken extra measures: they have guaranteed debts, they have partially or completely nationalized banks, they have forced weak institutions to merge with stronger ones, they have expanded their balance sheets to an extraordinary extent. And yet this, too, has not been enough.

So now the central bankers have thrown up their hands, and asked for help to stimulate spending through tax cuts and government expenditures. Because they have run out of means to "keep the money supply growing smoothly."

Today, we have reached the end of the line for the Chicago view of financial deregulation. Friedman thought (a) that the central bank could exercise enough influence over the money supply to effectively control it, and (b) that banks and other financial intermediaries would be regulated tightly enough that what is now happening would be impossible. But he never resolved the tension between his view that banks need controls and the Chicago view that business must be unfettered.

Monetarism may well make a comeback -- as a doctrine that is good enough for normal times. For in normal times "keep the money supply growing smoothly" does appear to be a relatively easy task, a minor adjustment to laissez-faire that can be performed by a small number of qualified technocrats. Unfortunately, not all times are normal.

Brad DeLong is a professor in the Department of Economics at U.C. Berkeley; chair of its Political Economy major; a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research; and from 1993 to 1995 he worked for the U.S. Treasury as a deputy assistant secretary for economic policy. He has written on, among other topics, the evolution and functioning of the U.S. and other nations' stock markets, the course and determinants of long-run economic growth, the making of economic policy, the changing nature of the American business cycle, and the history of economic thought.

-

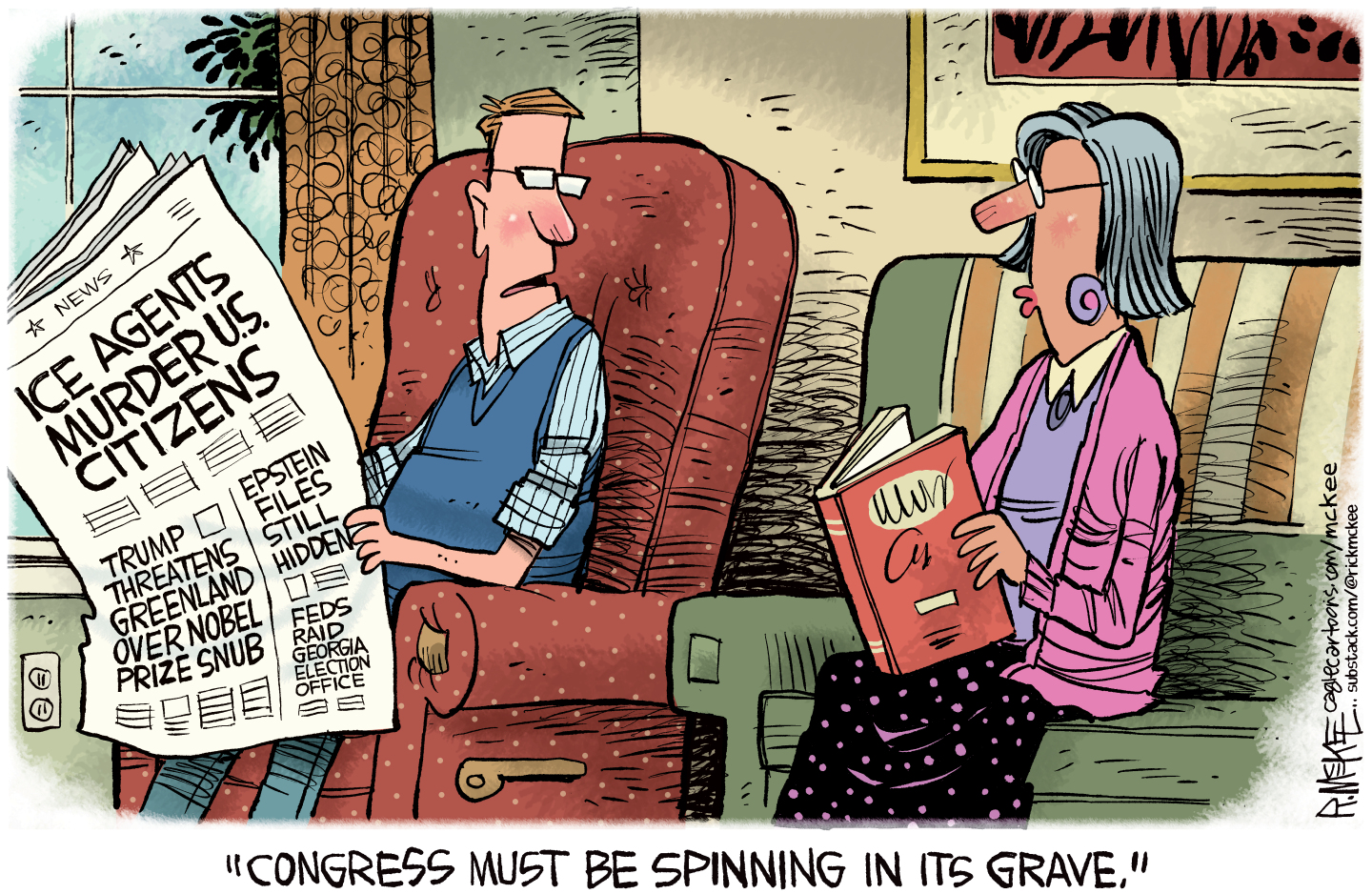

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

Issue of the week: Yahoo’s ban on working from home

feature There’s a “painful irony” in Yahoo’s decision to make all its employees come to the office to work.

-

Issue of the week: Another big airline merger

feature The merger of American Airlines and US Airways will be the fourth between major U.S. airlines in five years.

-

Issue of the week: Feds’ fraud suit against S&P

feature The Justice Department charged S&P with defrauding investors by issuing mortgage security ratings it knew to be misleading.

-

Issue of the week: Why investors are worried about Apple

feature Some investors worry that the company lacks the “passion and innovation that made it so extraordinary for so long.”

-

Issue of the week: Does Google play fair?

feature The Federal Trade Commission cleared Google of accusations that it skews search results to its favor.

-

Issue of the week: The Fed targets unemployment

feature By making public its desire to lower unemployment, the Fed hopes to inspire investors “to behave in ways that help bring that about.”

-

Issue of the week: Is Apple coming home?

feature Apple's CEO said the company would spend $100 million next year to produce a Mac model in the U.S.

-

Issue of the week: Gunning for a hedge fund mogul

feature The feds are finally closing in on legendary hedge fund boss Steven Cohen.