Marlene Dumas: Measuring Your Own Grave

The Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art is offering a retrospective of the work of Marlene Dumas.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Marlene Dumas: Measuring Your Own Grave

Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art

Through Sept. 22

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Marlene Dumas is an icon of feminist art, said Christopher Knight in the Los Angeles Times. Her paintings don’t shy from exploring issues of gender, power, and violence, “in pictures derived from pornography” or, in one case, from images of Marilyn Monroe’s autopsy. Yet this retrospective at Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art suggests that what truly sets apart her work is its philosophical depth. Death is a major theme in all Dumas’ paintings. The somnolent young girl in Reinhardt’s Daughter, for instance, looks so “black and bruised” that she seems to be a corpse, and the mortality-soaked mood of such canvases calls to mind masters such as Goya and Manet. “Talk about ambition!” Her painting techniques, as well, engage with major (male) painters in the European tradition. Measuring Your Own Grave (2003) “looks to nothing less than Leonardo da Vinci.” Her contorted figure, arms extended out to the edge of the frame, is a moody twist on his elegant and rationally proportioned Vitruvian Man.

The painting achieves its effect through a clever optical trick, said Christopher Miles in the LA Weekly. At first glance, the central figure seems to be sitting on a background split horizontally between black and white. But the image also can be seen another way, “with the bottom half of the canvas becoming a ground plane upon which the figure stands, bent over at the waist.” This simple painting delivers a punch to the gut more effectively than Dumas’ more overtly shocking images. As in all her best works, the painter’s lively brush relieves the morbidness of her subjects with “a kind of sideways exuberance, a tarnished joie de vivre.” These contradictory tendencies make her retrospective an unforgettable cocktail of “pleasure and disturbance.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

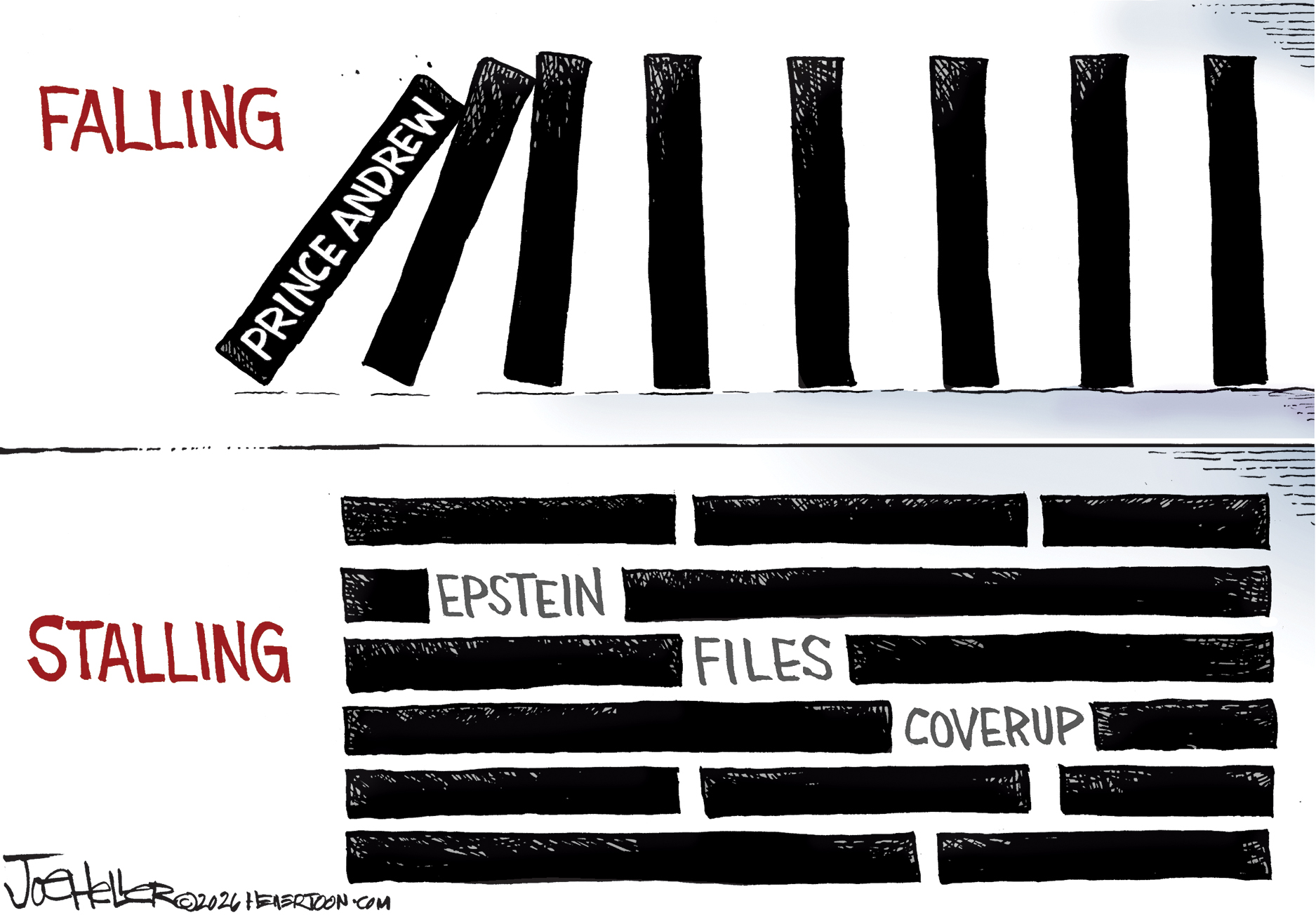

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

If/Then

feature Tony-winning Idina Menzel “looks and sounds sensational” in a role tailored to her talents.

-

Rocky

feature It’s a wonder that this Rocky ever reaches the top of the steps.

-

Love and Information

feature Leave it to Caryl Churchill to create a play that “so ingeniously mirrors our age of the splintered attention span.”

-

The Bridges of Madison County

feature Jason Robert Brown’s “richly melodic” score is “one of Broadway’s best in the last decade.”

-

Outside Mullingar

feature John Patrick Shanley’s “charmer of a play” isn’t for cynics.

-

The Night Alive

feature Conor McPherson “has a singular gift for making the ordinary glow with an extra dimension.”

-

No Man’s Land

feature The futility of all conversation has been, paradoxically, the subject of “some of the best dialogue ever written.”

-

The Commons of Pensacola

feature Stage and screen actress Amanda Peet's playwriting debut is a “witty and affecting” domestic drama.