Review of reviews: Art

The Art of Lee Miller

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Art of Lee Miller

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Through April 27

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Lee Miller is one of those rare figures whose “life story has become inextricable from her art,” said Katherine Stephen in The Christian Science Monitor. Beautiful, brilliant, and brave, Miller began her career as a model but gained fame as a photographer. “It is difficult to think of a single other female photographer who started her career in front of the camera but chose to adopt a life behind one.” But, then, Miller always was exceptional. In the Paris of the 1920s, she studied (and slept) with pioneer surrealist Man Ray. Later she worked as one of six women accredited as photographers during World War II. Miller brought a whiff of glamour to every setting, but earned a place as a pioneer female artist by “rejecting style in factor of substance” and turning her surrealist eye toward everyday life.

The influence of surrealism is obvious in works such as Portrait of Space, which shows the Egyptian desert through the frame of a torn window screen, said Edward Sozanski in The Philadelphia Inquirer. But in fact the lessons she learned from Man Ray crept into all of her work. “Even during the war, surrealism never entirely disappeared from her works, as evidenced by a picture of two women wearing fire masks and goggles that make them look sinister.” Unlike Man Ray, Miller didn’t synthetically compose surrealistic images in her studio or darkroom. Instead, “she observed slight distortions of reality and magnified their oddness in the way she framed them in her camera.” It doesn’t get more surrealistic than Miller’s image of “two surgically severed breasts—the aftermath of a mastectomy.” You can hardly believe the image is real—but it is.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

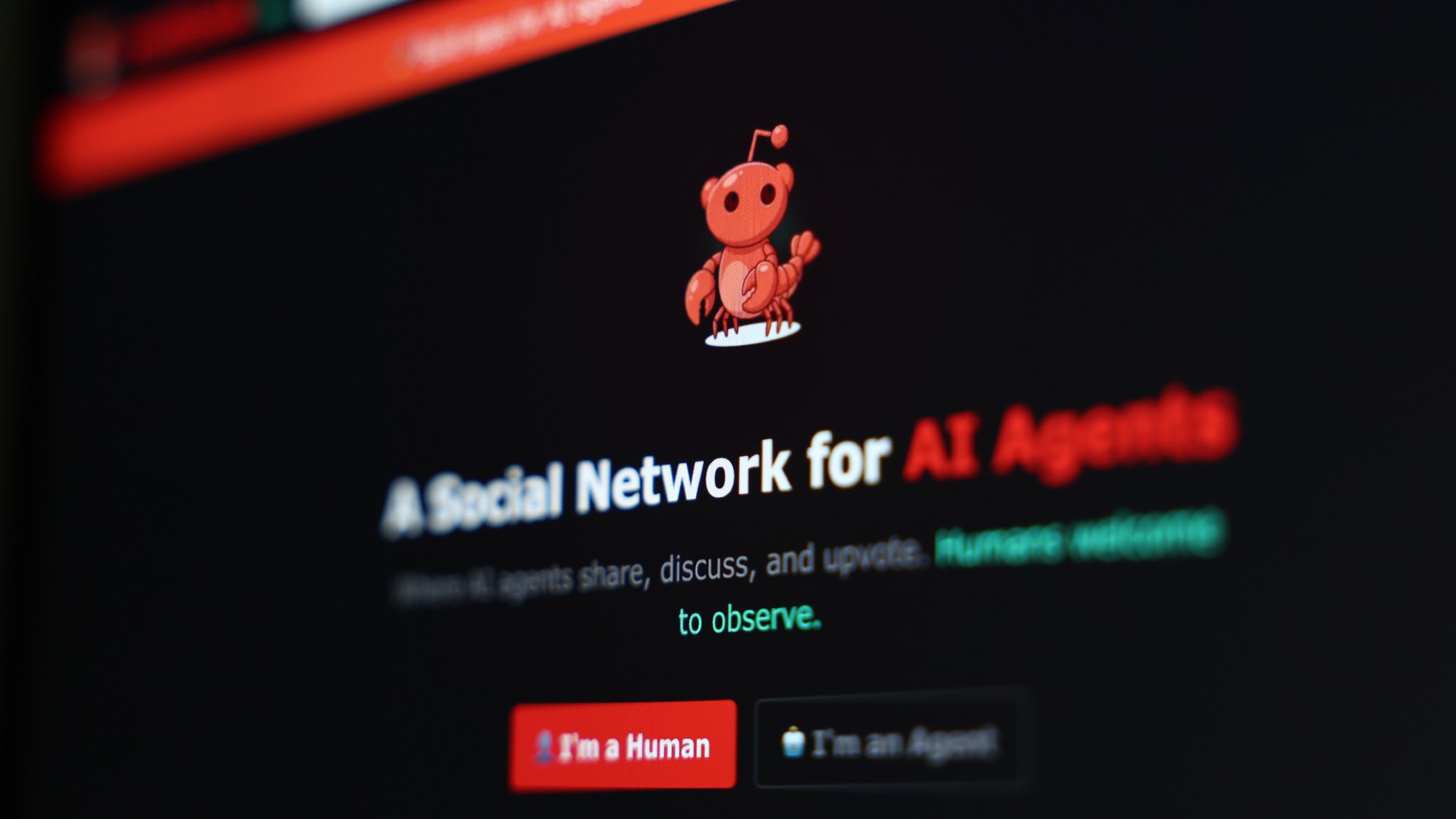

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg

-

If/Then

feature Tony-winning Idina Menzel “looks and sounds sensational” in a role tailored to her talents.

-

Rocky

feature It’s a wonder that this Rocky ever reaches the top of the steps.

-

Love and Information

feature Leave it to Caryl Churchill to create a play that “so ingeniously mirrors our age of the splintered attention span.”

-

The Bridges of Madison County

feature Jason Robert Brown’s “richly melodic” score is “one of Broadway’s best in the last decade.”

-

Outside Mullingar

feature John Patrick Shanley’s “charmer of a play” isn’t for cynics.

-

The Night Alive

feature Conor McPherson “has a singular gift for making the ordinary glow with an extra dimension.”

-

No Man’s Land

feature The futility of all conversation has been, paradoxically, the subject of “some of the best dialogue ever written.”

-

The Commons of Pensacola

feature Stage and screen actress Amanda Peet's playwriting debut is a “witty and affecting” domestic drama.