Obituaries

Richard Widmark, Dith Pran

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The sturdy movie star who defied easy typecasting

Richard Widmark

1914–2008

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Few actors have made as memorable a movie debut as Richard Widmark. In Kiss of Death (1947), he played Tommy Udo, a sadistic gangster who cackles gleefully as he ties up an old woman in her wheelchair and pushes her down the stairs to her death. “I’d never seen myself onscreen, and when I did, I wanted to shoot myself,” Widmark recalled. But the part won him an Oscar nomination and led to a 44-year film career, during which he portrayed everything from heavies to heroes.

The hero parts came later, said the Los Angeles Times. After graduating from Lake Forest College in Illinois, the Minnesota native taught drama there, and on radio he played what he called “young, neurotic guys.” After Kiss of Death, he specialized in “psychotic tough guys and nutballs.” In The Street With No Name (1948), Widmark was a crooked, hypochondriac fight promoter; in Road House (also 1948), he was a veteran driven mad by sexual jealousy. He spouted such bigoted bile at Sidney Poitier’s character in 1950’s No Way Out that he apologized after each take. Widmark was so believable that people began attacking him. “I remember walking down the street in a small town and this lady coming up and slapping me. ‘Here, take that, you little squirt,’ she said. Another time I was having dinner in a restaurant when this big guy came over and knocked me right out of my chair.”

Soon, though, he was playing solid leading roles, said the London Times. In Panic in the Streets (1950), he was a public-health officer tracking down a plague carrier; in Halls of Montezuma (also 1950), he played a hard-charging Marine. Still, “as a hero he could never compete in the same league as Cagney, Bogart, or Flynn; he had none of their bravura or sex appeal.” Despite being 5-foot-11, Widmark had “slightly weak good looks” that made him appear “small onscreen.” That, combined with a high forehead, “eyebrows so fair they had to be penciled in onscreen,” and “a soft jaw, made him look like a man who had learned to fight to be noticed.”

But as he matured, Widmark exploited his off-center qualities, said The Washington Post. “His good guys were often misanthropes or men fixated on a mission.” He was a single-minded prosecutor in Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), an unconventional Army officer who helps the Indians in Cheyenne Autumn (1963), and an “obsessed detective” in Madigan (1968). In real life, Widmark was a soft-spoken pipe smoker who disdained fame, which he thought was “all baloney and could blow away in a minute.” Indeed, as he turned 60, his roles became less memorable. “He accepted the part of the corpse in Murder on the Orient Express (1974) just so he could say John Gielgud played his valet.” In the all-star disaster of a bee movie, The Swarm (1978), he declared, “I’m going to be the first officer in U.S. battle history to get his butt kicked by a mess of bugs!”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Widmark’s last movie was True Colors in 1991. He is survived by his second wife and a daughter from his first marriage.

The Cambodian photographer who survived ‘the killing fields’

Dith Pran

1942–2008

By all rights Dith Pran, who succumbed last week to pancreatic cancer, should have died some 30 years ago. During the Khmer Rouge’s reign of terror in Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, some 1.5 million of the country’s 7 million inhabitants perished. Dith endured torture, starvation, and other atrocities, finally emerging to tell the world of the hell he had endured.

Dith was precisely the sort of person the Khmer Rouge was “hell-bent” on exterminating, said the Los Angeles Times. Born to a middle-class family, “he learned French in school and taught himself English.” After high school, he worked as an interpreter for the U.S. Military Assistance Group. When Cambodia severed relations with the U.S. in 1965, “he became a guide and translator for foreign journalists,” including Sydney Schanberg of The New York Times, whose life he would save by pleading with the Khmer Rouge when they captured Schanberg and other reporters. When the capital, Phnom Penh, fell in 1975, Dith’s “life became an unremitting nightmare”

as the Khmer Rouge began “a radical restructuring of Cambodian life,” emptying the cities, forcing the population into the countryside, and killing intellectuals, professionals, and anyone with Western ties.

To survive, Dith “passed himself off as a humble taxi driver” and dressed in peasant clothes, said the London Independent. He worked in the fields up to 14 hours a day; his daily food ration was a spoonful of rice, supplemented with rats, snails, and insects. Once, when he stole some rice kernels, “he was caught, beaten with machetes, and paraded before the local community for a ritual humiliation.” Dith managed to steal away in 1977 and begin searching for his family, only to find that “his father had died of starvation and four of his five siblings had been killed.” His mother later died of malnutrition. He made an even more ghastly discovery: “the remains of as many as 5,000 of his former neighbors scattered among the trees and clogging up water wells. Such were the notorious killing fields.” Dith later said, “The grass grew taller and greener where the bodies were buried.”

Not until 1979 was Dith able to cross into Thailand to safety, said The New York Times. “His 60-mile trek to the border was fraught with danger. Two companions were killed by a land mine.” But when he arrived, on Oct. 3, “an overjoyed Schanberg flew to greet him.” Soon, he was reunited with his wife and children in San Francisco. Schanberg’s book about his ordeal, The Death and Life of Dith Pran, was made into the critically acclaimed 1984 movie The Killing Fields. With Schanberg’s help, Dith settled down to a long career as a photographer with the Times, but his primary mission remained informing the world about Cambodia’s genocide in the hope that its monstrosity would never be repeated. “I am a one-person crusade,” he said. “I must speak for those who did not survive and for those who still suffer.”

-

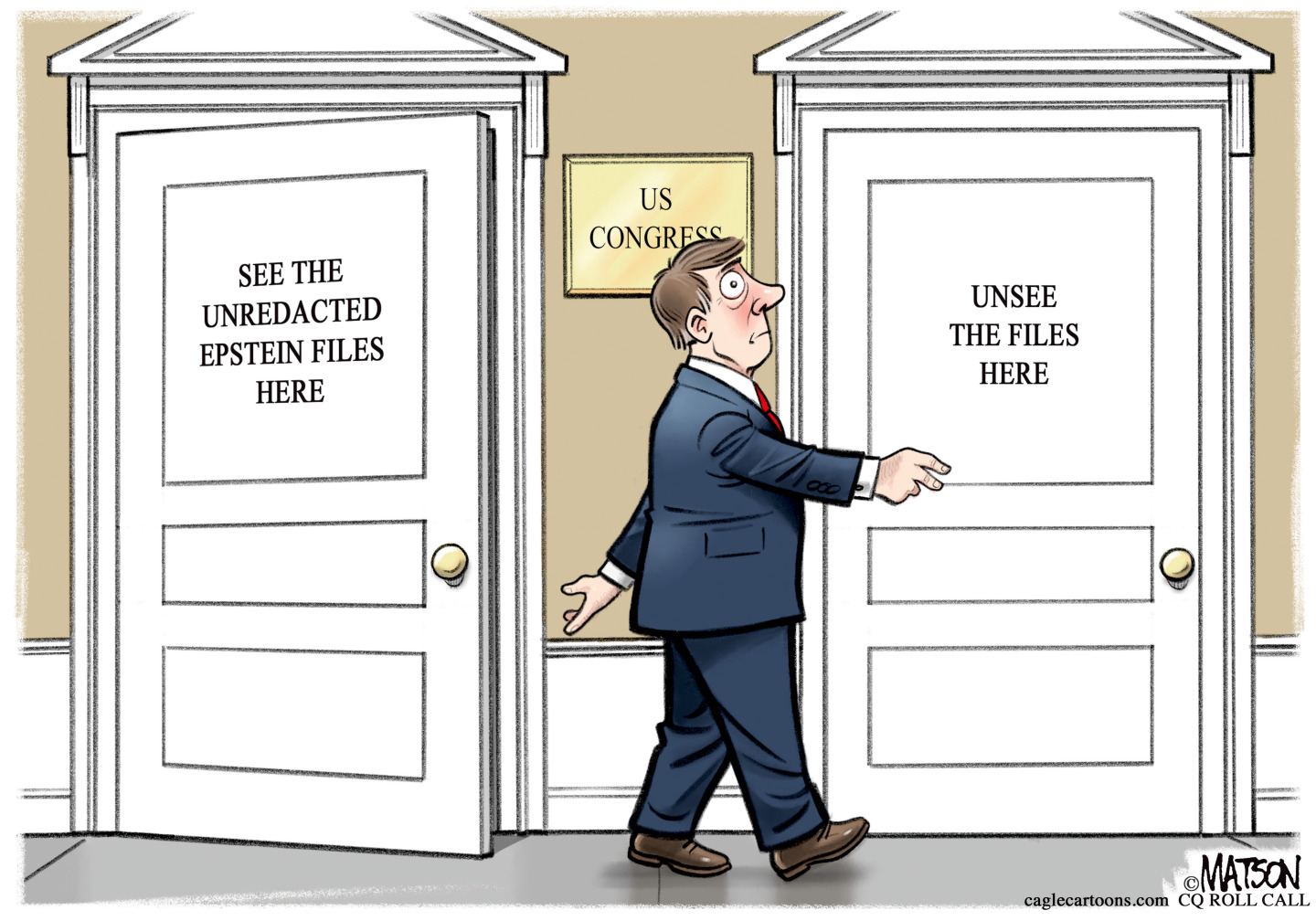

Political cartoons for February 11

Political cartoons for February 11Cartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include erasing Epstein, the national debt, and disease on demand

-

The Week contest: Lubricant larceny

The Week contest: Lubricant larcenyPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’Feature O'Hara cracked up audiences for more than 50 years

-

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flame

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flameFeature The fan favorite died at 78

-

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new France

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new FranceFeature The actress retired from cinema at 39, and later become known for animal rights activism and anti-Muslim bigotry

-

Joanna Trollope: novelist who had a No. 1 bestseller with The Rector’s Wife

Joanna Trollope: novelist who had a No. 1 bestseller with The Rector’s WifeIn the Spotlight Trollope found fame with intelligent novels about the dramas and dilemmas of modern women

-

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like water

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like waterFeature The revered building master died at the age of 96

-

R&B singer D’Angelo

R&B singer D’AngeloFeature A reclusive visionary who transformed the genre

-

Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley

Kiss guitarist Ace FrehleyFeature The rocker who shot fireworks from his guitar

-

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film Festival

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film FestivalFeature Redford’s most lasting influence may have been as the man who ‘invigorated American independent cinema’ through Sundance