Curveball: Spies, Lies, and the Con Man Who Caused a War

The entire war in Iraq can be blamed on the lies of a down-and-out Baghdad engineer, says investigative reporter Bob Drogin. In 1999, long before the world knew him by the code name Curveball, this 20-something former government employee flew to Munich se

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Curveball: Spies, Lies, and the Con Man Who Caused a War

by Bob Drogin

(Random House, $26.95)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The entire war in Iraq can be blamed on the lies of a down-and-out Baghdad engineer, says investigative reporter Bob Drogin. In 1999, long before the world knew him by the code name Curveball, this 20-something former government employee flew to Munich seeking a luxurious Western life. To bolster his appeal for asylum, he began spinning tales about a secret weapons program run by Saddam Hussein. Unfortunately, German intelligence officers believed him. Four years later, an artist’s rendering of a mobile biological weapons lab was the centerpiece of U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell’s argument for deposing Saddam. The lab was the product of Curveball’s imagination.

Even though we know how this story ends, said Judith Miller in The Wall Street Journal, Drogin brings suspense to his detailed retelling. The CIA concluded far too late that none of Curveball’s stories was true. The salient drama came before the war, when “childish bickering” between dysfunctional U.S. intelligence agencies and prickly relations with their German counterparts caused initial misjudgments to metastasize. Drogin infuses “fascinating detail” into this story but lets his rhetoric get away from him. Though he claims some U.S. officials told outright lies about the Iraqi weapons intelligence, he doesn’t prove anyone’s mendacity. What’s more, the idea that Curveball “caused” the war only holds up if one believes that without his evidence, Saddam would not have been judged a threat.

Drogin doesn’t ever “scold or lecture,” though, said Lisa Medchill in The New York Observer. “He does what a good reporter must,” focusing on his narrative and turning what could have been a dry autopsy into “a gripping spy story.” Better still, said Spencer Ackerman in The Washington Monthly, Drogin’s account illustrates why “it’s only a matter of time before another Curveball poisons the intelligence well.” Assigning blame for failures in 2002 and 2003 is not reason enough to revisit this story. The timely and valuable accomplishment of Curveball is that it shows precisely how the intelligence agencies we have today bring out “the worst impulses of intelligence professionals.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

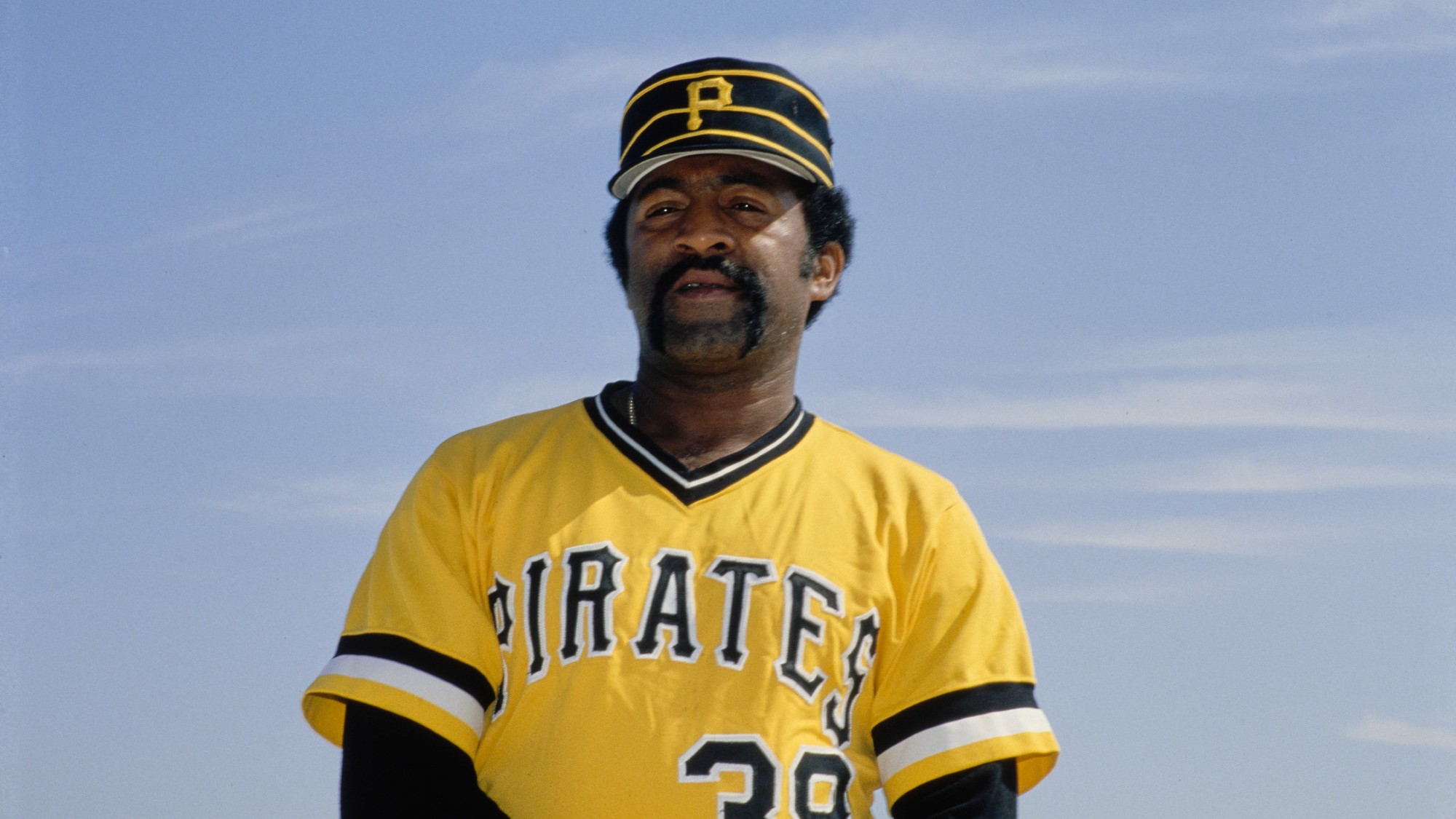

The 9 best steroid-free players who should be in the Baseball Hall of Fame

The 9 best steroid-free players who should be in the Baseball Hall of Famein depth These athletes’ exploits were both real and spectacular

-

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What to watch on TV this February

What to watch on TV this Februarythe week recommends An animated lawyers show, a post-apocalyptic family reunion and a revival of an early aughts comedy classic