Patrick Modiano and the art of silence

A review of the Nobel Prize winner's Suspended Sentences

Theodor Adorno famously declared, "To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric," a statement that is almost always cited (and misconstrued) to make the opposite case, for the enduring relevance of art in the face of the unspeakable. It is hard to argue with this point, since the Holocaust has proven to be a veritable font of art, both good and bad, in the 70 years that have passed since the end of World War II. But as far as Adorno and his contemporaries were concerned, much of Western art, newly cast in the lurid glare of the war, had become flawed, inadequate, and subtly complicit in a worldview that had given birth to Nazism and the gas chambers. It had to be replaced by something new. For European literature, this project began with those who had lived through the atrocities of the Nazi era — Elie Wiesel, Primo Levi, Imre Kertesz, Tadeusz Borowski — and was carried on by a subsequent generation of writers born in the Holocaust's long shadow.

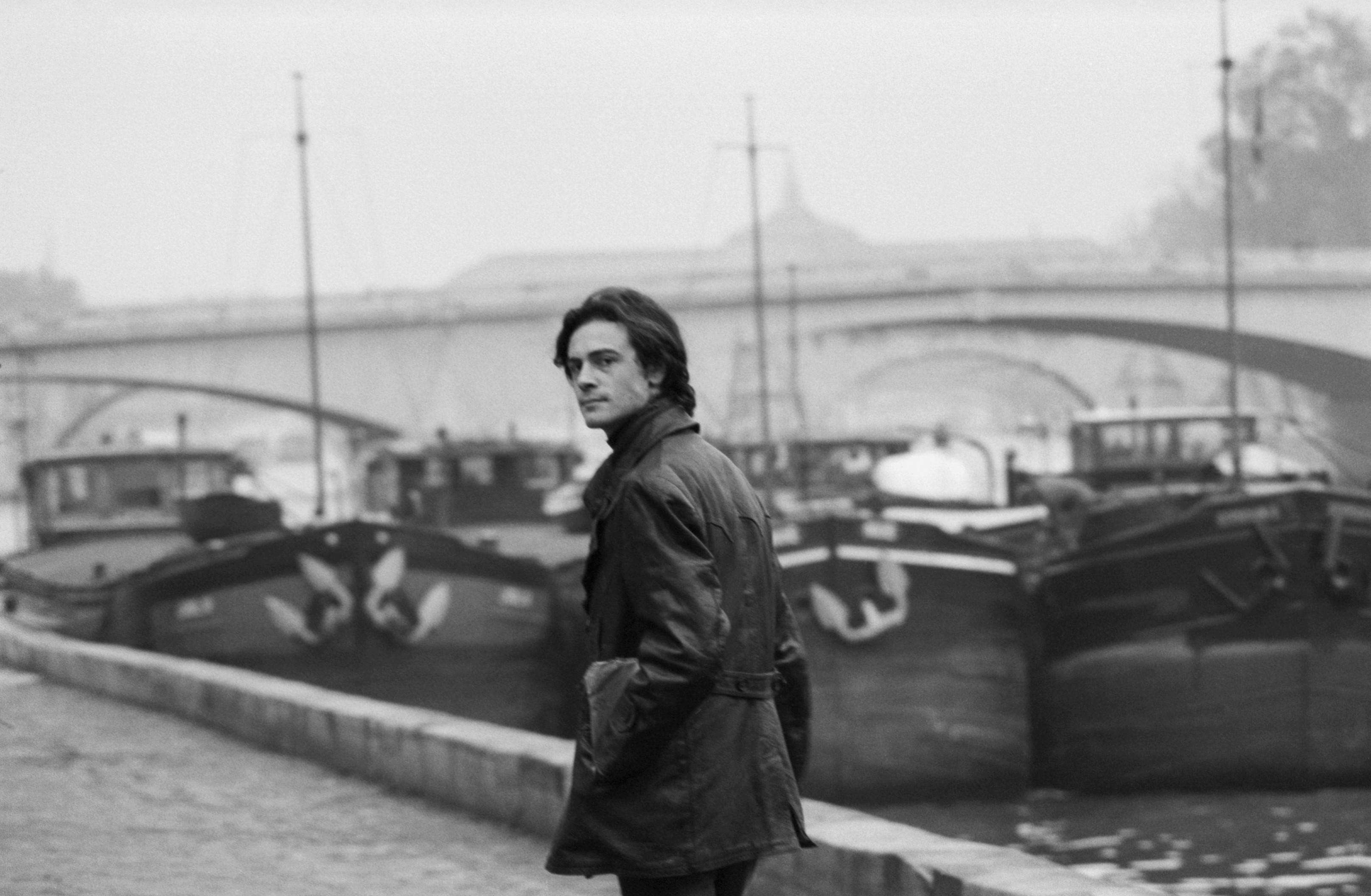

One of these writers is the Frenchman Patrick Modiano, who in October of last year was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was then a virtual unknown among Anglophone readers, sending many of them in curious pursuit of the scant few of his books that have been translated into English and remain in print. By way of introduction, the Nobel committee hailed his work in the "art of memory," while others noted Modiano's frequent use of the detective novel form, all of which suggested that he was some felicitous hybrid of Marcel Proust and Georges Simenon. But to judge by Suspended Sentences — a collection of three linked novellas from the late 1980s and early 1990s recently translated into English by Mark Polizzotti — the writer Modiano most resembles is W.G. Sebald, who before his sudden death in a car crash in 2001 was widely considered a lock for a Nobel for his haunted, mesmeric work on the Holocaust's aftermath. Like Sebald, Modiano blends fact and fiction, memoir and reportage. Both are obsessed with unearthing lives buried under the avalanche of time. But perhaps the most compelling trait they share, one so striking as to suggest a larger phenomenon, is the extremely oblique way in which they address their subject, as if their books are mere points of light against a vast vault of depthless silence.

Modiano's itch, the place in time he returns to again and again, is Paris of the Nazi occupation, when French officials in the Vichy government assisted the Germans in exerting control over the country and corralling Jews to be sent to the concentration camps. The novellas in Suspended Sentences are indeed detective stories, and the mysteries they attempt to solve involve characters whose past lives are obscured by the smoldering murk of that era. In "Afterimage," a young writer tries to assemble a coherent narrative around an enigmatic photographer, Francis Jansen, who during the occupation was rounded up by the police and released under curious circumstances. The title story is about two children abandoned by their mother to be raised by a gang of petty criminals and assorted members of the Parisian demimonde; the children's father was also arrested during the occupation but spared deportation, and is rumored to have had ties to the Rue Lauriston gang. The father shows up again in "Flowers of Ruin," which is largely about a shadowy character named Pacheco who may or may not have collaborated with the Nazis.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As Polizzotti notes in his introduction, these details come straight from Modiano's life. His father, Albert, was arrested during the occupation as an undocumented Jew, only to be released without explanation. He had black market ties to the Carlingue, the historical version of the Rue Lauriston gang, which was "part band of thieves, part Gestapo auxiliary," in Polizzotti's words. (Modiano shares a similarly conflicted biography with another postwar writer, Harry Mulisch, whose Jewish mother and he were able to avoid deportation due to the efforts of his father, a Nazi collaborator in occupied Holland; the roles of victim and collaborator are masterfully intertwined in Mulisch's book The Assault.) Meanwhile, Modiano's mother was an actress who was often away on tour, leaving Modiano and his brother Rudy to be looked after by the disreputable cast of characters featured in the title story.

But if the occupation provides the fulcrum around which these novellas revolve, it is a distant one. "Suspended Sentences," for example, is content to dawdle in the long days and nights of the boys' unconventional childhood, before the dark legacy of the past abruptly catches up to them (as it eventually does to everyone in these novellas). There is one moment, a searchlight through the fog, when the past is laid bare and the narrator describes how his father escaped the Drancy transit camp in Paris.

One night, someone showed up in an automobile at the Quai de la Gare and had my father released. I imagined — rightly or wrongly — that it was a certain Louis Pagnon, whom they called 'Eddy' and who was shot after the Liberation with members of the Rue Lauriston gang, to which he belonged.

Then the past closes up again, taking its secrets with it.

"Writing ought to be, as it were, a saving, or at least an attempt at the saving, of souls," Sebald once said. Modiano believes this, too. In "Afterimage," he writes of the photographer Jansen, "[I]t would make me glad if these pages rescued him from oblivion — though that oblivion is his own doing, deliberately sought." The characters in Suspended Sentences are constantly disappearing into mist and around corners, and often register only as silhouettes and hazy outlines when they do appear, a source of existential despair for the narrator. In "Flowers of Ruin," he writes:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As hard as I pressed my forehead against the glass and peered at the dark gray wall, no trace of him remained. He had vanished in that sudden way that I'd later notice in other people, like my father, which leaves you so puzzled that you have no choice but to look for proofs and clues to convince yourself these people had really existed.

The solution to this conundrum, seemingly, is art. At one point, the narrator in "Afterimage" turns on the television and is surprised to see an old acquaintance, an actor, on the screen. He marvels at the impermanence of reality when compared to what flickers before him:

There, onscreen, he was crossing a hotel corridor, and I thought it really strange that one could pass from a world in which everything ended to another, freed from the laws of gravity, in which you were suspended for all eternity: from that evening on Rue Froidevaux, of which nothing remained except the fading echoes in my memory, to those several seconds captured on film, in which Deckers would cross a hotel corridor until the end of time.

It is not only souls that Modiano plucks from the void, but his beloved Paris as well. "One could easily read these novellas as a three-part love song to a Paris that no longer exists," Polizzotti writes. It appears that Modiano has wholeheartedly embraced Proust's elegiac assertion that "houses, roads, avenues are as fleeting, alas, as the years." For both writers, cities are not static entities, but as fluid as time; the places of our lives do not occupy a geographic space, but are memories; and if they are to exist outside the mind they must be rendered into art. This process of artistic excavation is brilliantly expressed in a scene in "Afterimage" in which Paris itself becomes a multi-layered fresco:

He had told me that he shredded street posters himself to uncover the ones hidden beneath the newer strata. He pulled the strips down layer by layer and photographed them meticulously, stage by stage, down to the last scraps of paper that remained on the billboard or stone wall.

But for all Modiano's sleuthing, his narrators have little to show for it. The characters they investigate never come together in any satisfactory way; they remain as elusive as ever, and sometimes become even more opaque. Then there are the immense portions of historical narrative that remain steadfastly unaddressed, like concentric rings that grow steadily darker as they ripple out from the penumbral region of Modiano's fictions — the occupation; beyond that, Nazi Germany; and farther east, the fate of all the Jews, French and otherwise, consigned to Auschwitz and Treblinka.

Sebald's novels, too, are reluctant to come out and say what happened. One reason for this, as Karl Ove Knausgaard wrote in a recent essay discussing Paul Celan and Peter Handke, is that history has a way of subsuming individuals into movements and eras, battles and rebellions. "Like the names 'Auschwitz' and 'Treblinka', 'Holocaust' is something we refer to, something in history, where each incident, each life, each moment is firmly attached to the emblem of the name," Knausgaard wrote. "The act of naming is another form of disappearing. Consequently, the poem cannot mention Auschwitz; the diminution is too great, and it describes nothing of what took place there." (Knausgaard's My Struggle, which borrows the title of Hitler's notorious memoir cum manifesto and concludes with a book-length essay on Nazism, is arguably a stake marking a third generation of post-Holocaust fiction — which is to say that the story of modern European literature continues to be about art's response to fascism.)

The perceived inadequacy of "naming," which was compounded by the Nazi perversion of words like "fatherland and "family," is indicative of the postwar generation's wariness of the redemptive power of literature and art more generally. Modiano expresses this in an episode in "Afterimage" in which Jansen, newly released from the transit camp for Jews that should have sent him to his doom, searches for the relatives of a fellow detainee who wasn't so lucky. He finds none of them, "[a]nd so, feeling helpless, he'd taken those photos so that the place where his friend and his friend's loved ones had lived would at least be preserved on film. But the courtyard, the square, and the deserted buildings under the sun made their absence even more irremediable."

In other words, there are only so many people the artist can save. It is as if the sum effect of Suspended Sentences is a gesture at a silence that rings far louder than the words on the page — the silence of the millions of souls who died in the Holocaust, and broader still, the silence of a ceaseless loss that stretches across millennia and defines our time on Earth. Suspended Sentences, then, is a purposeful act of misdirection, a candle that only serves to emphasize the surrounding darkness. As the narrator in "Afterimage" says of Jansen, "A photograph can express silence. But words? That he would have found interesting: managing to create silence with words."

Modiano has managed to do just that. He has shown that while art after Auschwitz may not be barbaric, even after all these years, it is no solace either.

Ryu Spaeth is deputy editor at TheWeek.com. Follow him on Twitter.

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

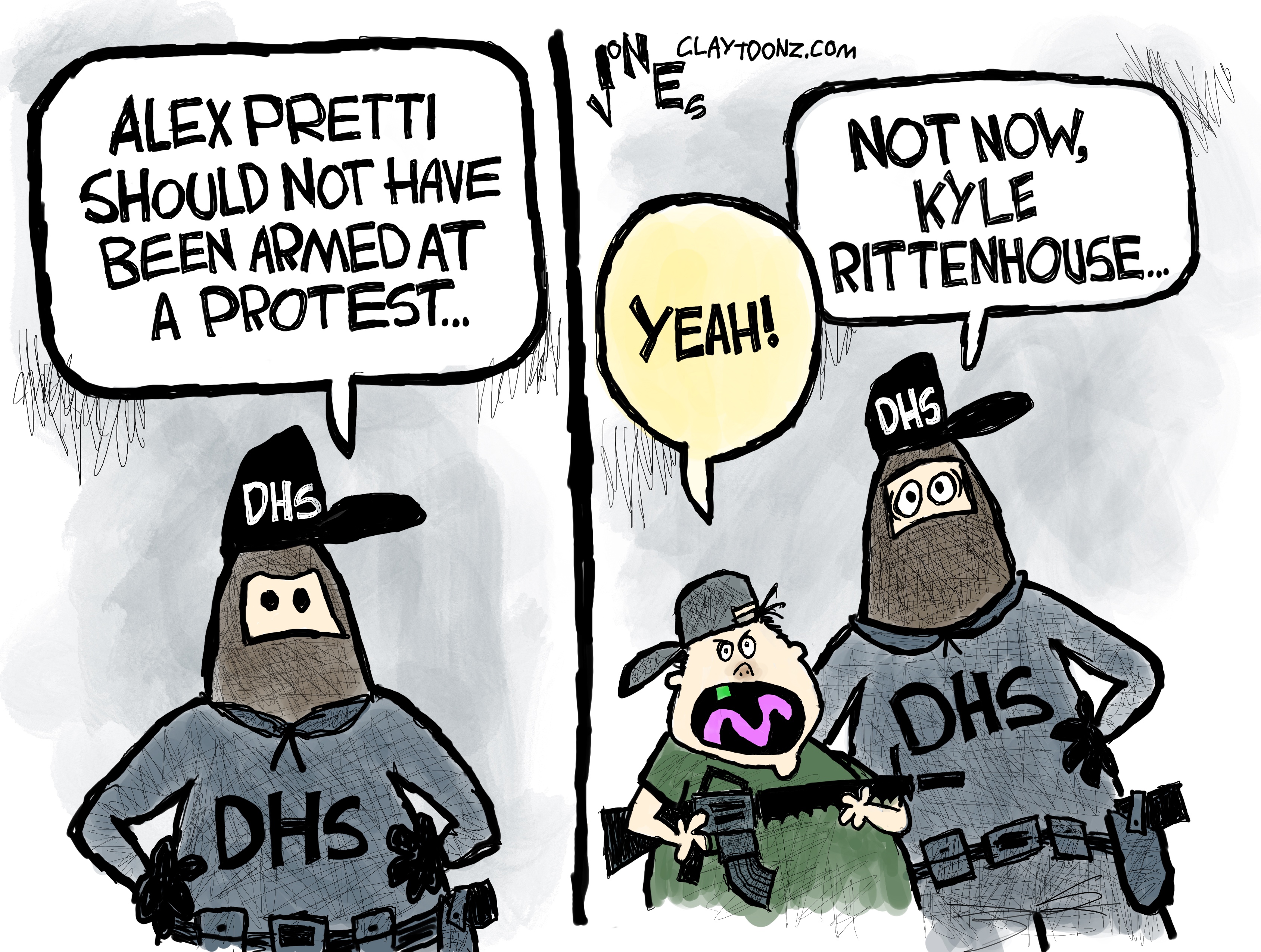

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more