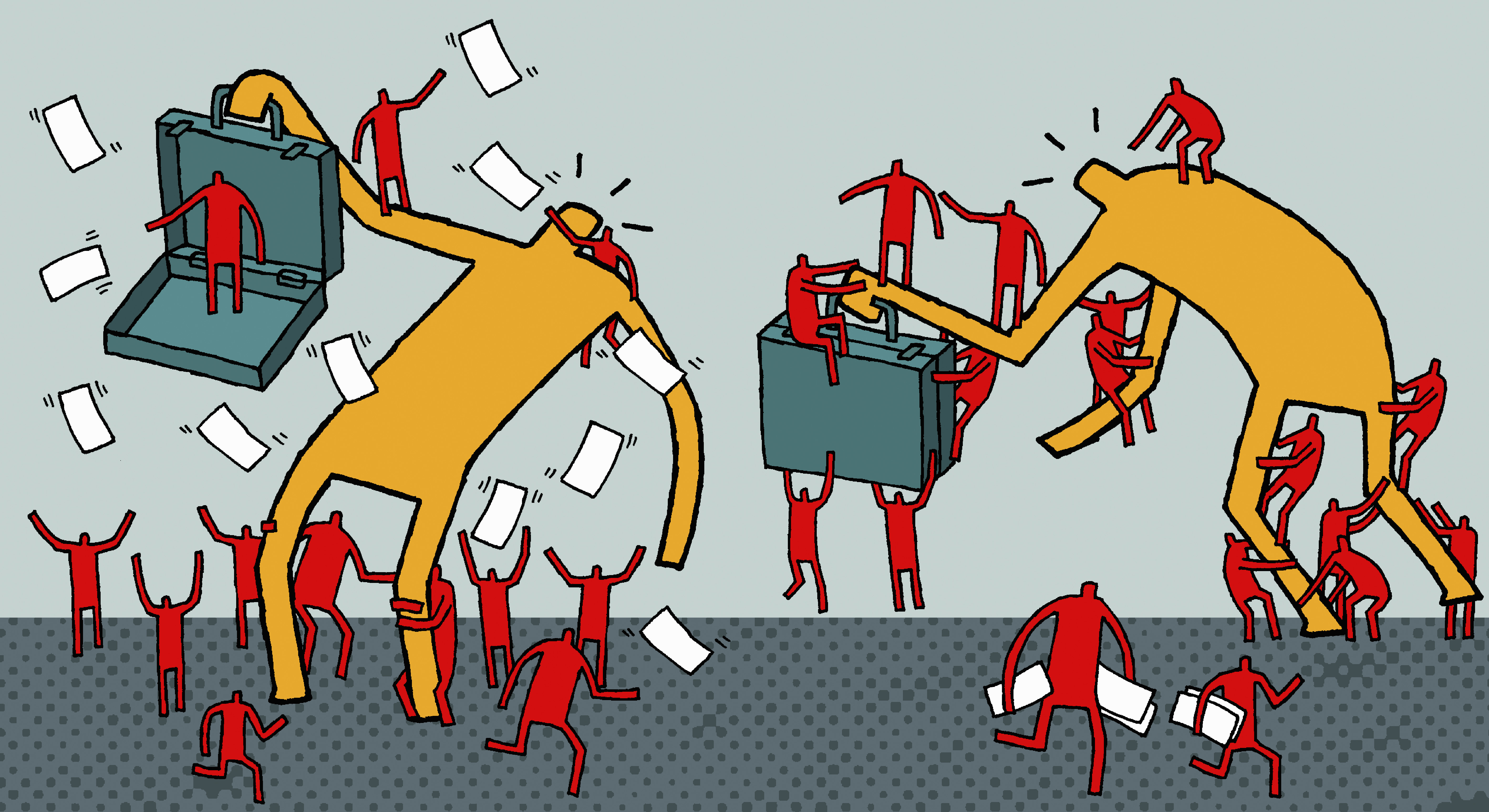

Meet the new workers' movement that is terrifying the wealthy and the powerful

Micro unions are here. And Big Business isn't happy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Thursday, Sen. Johnny Isakson (R-Ga.) re-introduced legislation to torpedo "micro unions," the latest labor movement to terrify business management, right-wingers, and capitalists in general.

They aren't actually anything new, just a variation on long-standing labor-organizing practices that have come back into prominence. "Micro union" is a recently coined term of art for bargaining units that encompass one category of workers at a business — the cosmetics workers at a Macy's, for example — instead of the more traditional model of organizing all the workers for the business into one single bargaining unit.

In 2011, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decided a group of certified nursing assistants at a nursing home constituted an appropriate bargaining unit in themselves, in a decision called Specialty Healthcare. In 2013, that decision got the stamp of approval from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. In 2014, the NLRB applied its logic to the aforementioned Macy's cosmetics workers.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Since then, union critics and business interests have been scrambling to respond. Retail industry groups told The Hill that the NLRB’s Macy's decision would "pave the way for micro unions at thousands of retail stores around the country." Isakson has made multiple attempts to pass his bill rolling back NLRB's decisions, with the backing of GOP heavy-hitters like Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.).

What's particularly interesting is the way the arguments made by micro-union critics run headlong into the arguments made by fans of right-to-work laws, which seek to prevent unions from coopting workers.

"The problem with Specialty Healthcare is not the smallness of the unions, but the way the lines are gerrymandered within a workplace," Jim Plunkett, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s director of labor law policy, told The Hill in 2014. "They're allowed to cherry pick the employees in the workplace that they know will be supportive of the union."

But recall that the argument for right-to-work laws is that, even if they weaken unions, they also prevent unions from negotiating contracts that would force every worker covered by the bargaining agreement to join a union and pay dues. This critique implies that picking the employees in the workplace you know will support the union and organizing just them into a bargaining unit is perfectly fine, yes?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yet when business groups and other opponents aren't calling it "gerrymandering," they're arguing that lots of small bargaining units will make management a lot more logistically difficult than having one big bargaining unit to deal with!

Unions appear to be damned if they do, and damned if they don't.

Jerry Howard, the CEO of the National Association of Home Builders, said, "We'll do our best to discourage these things from getting into our sector."

"It lets the union get their nose under the tent," said Michael Lotito, a management-side attorney in San Francisco.

To put it bluntly, this is not how people would talk if they were concerned about maximizing the common economic good and basic fairness — which is how union critics often paint their efforts. Right-to-work fans insist they're fine with unions as long as the workers themselves want the union, and see it as in their own best interests. If that's your logic, there's no intrinsic reason a non-unionized sector shouldn’t become unionized.

Of course, what this talk does sound like is people who recognize they're in a zero-sum battle over irreconcilable interests.

Under free market capitalism, people are not paid for how productive they are — as the theory of marginal productivity claims — but for how replaceable they are. Say the marginal productivity a worker brings to a firm is $40,000 a year. But let's say that worker is scared because the economy recently went through a big collapse and there are more people looking for work than there are jobs available. (You know, just for the sake of argument.) So they settle for $35,000 a year. The employer isn't going to then say, "Oh wait, that’s not fair! Here, let me pay you the other $5,000 too." They're going to pocket the $5,000 as profit.

If employers can get away with lower pay, with unsafe or degrading working conditions, or by squeezing demeaning emotional labor from their employees, they will do so. It increases the amount of revenue they can take home as profit, as opposed to pumping it back into better wages. And it increases their power to run their workplaces in whatever manner they see fit, regardless of what the workers themselves think.

Bargaining power is everything, and unions increase it for workers.

Employers "feel like the deck is stacked against them," said Amanda Wood, director of employment at the National Association of Manufacturers.

I'm sure they do. But unless we're expected to believe employers and business owners are the underdogs in the grand socioeconomic sweep of American life, and everyday workers are some colossus bestriding the landscape, seeing all their most petty desires met, it's unclear why we should prioritize employers' wounded feelings.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.