Why high schools should have mandatory film classes

It's time to get real about America's visual illiteracy

Over the five years I taught high school, I came to the realization that all my students were illiterate.

OK, that's hyperbole. They could all read books — but when it came to reading images, none of them knew montage from mise en scène. This, of course, despite a world that has never placed a greater value on visuals.

I have a proposal to fix this: High schools should make taking a course in film studies mandatory for graduation.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This suggestion will likely fill some of you with dread — dark visions of teachers falling asleep while the latest Transformers movie buzzes in the background. I often heard from parents and educators alike: Why do students need to take a class to learn how to watch movies?

It's true, of course, that anyone can watch movies without the kind of training you need to read books. But students should (hopefully) know how to read a sentence well before high school — what high school literature classes teach is how to read critically. High school film classes would do the same thing, only for images.

I think you'd find the students receptive. For the last four years of my teaching career, I taught a film history elective once a year. As we went along, learning about Black Maria and the Hays code and watching films from each era, we would also gradually build our tool kit for analyzing the films we watched, studying how to dissect form as well as absorb content.

The watershed moment in every class came near the beginning. After tracing the developing complexity of films through the silent era, we would take two paradigmatic silent features — The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and The Battleship Potemkin — and tear them apart as a workshop in understanding images. As the classes painstakingly examined the expressionist sets and grotesque makeup of Caligari, they began to grasp the emotional response and atmosphere that can be created through effective mise en scène. Even more revelations awaited in Battleship Potemkin, where they learned to identify how the director Eisenstein would place the camera for dramatic or emotional effect, and the power of cuts to build tension and plant ideas in your mind.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The idealist in me thinks this alone should be enough to justify my proposal. In a perfect world, every teenager would have the ability to grasp just how dizzying Buster Keaton's leaps from frame to frame are in Sherlock, Jr., and would fully appreciate the sumptuous slow motion of Wong Kar Wai's In the Mood for Love. In our results-oriented education system, however, where every decision must be justified through quantifiable impact on future productivity, I don't hold out much hope for convincing people that students should spend their time transforming into mini aesthetes.

Let me offer a more practical reason, then.

Students need the skills they would learn in a film studies class because our society's lack of visual literacy has handicapped our critical thinking and turned us into gullible consumers of images. In my more traditional role as a history teacher, I slowly learned the sheer faith students had in visual data. Photographs, charts, and even paintings were treated as bearers of indisputable (if frequently mysterious) facts, not rhetorically charged pieces of persuasion. Of course, you can see this in adults too, from the unquestioned circulation of clearly photoshopped images on Facebook to the utter credulity with which the stories offered to us by cable television news are accepted.

There would be many challenges in implementing mandatory film studies in high schools, but the biggest — a lack of instructors qualified to teach it — only points urgently to the need.

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

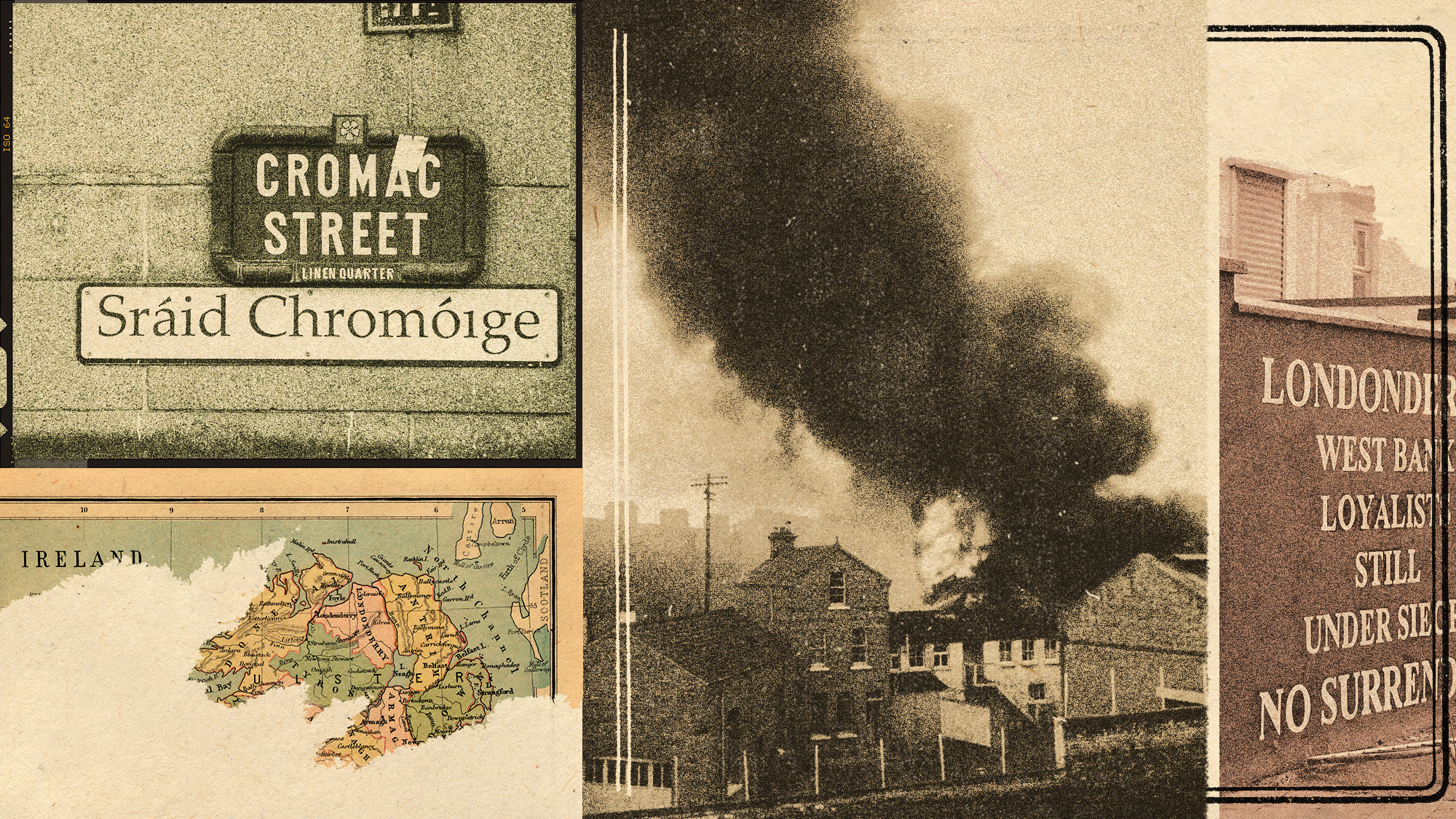

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion