How climate change is killing the aspen forests of the American Southwest

Beware of xylem cavitation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The early 2000s were a time of exceptional drought in the American Southwest. The year 2002 in particular was perhaps the driest in the last 500 years, according to tree-ring historical reconstructions.

This was bad news for the aspen trees of the Southwest, which died by the millions. But it also raised a scientific question: just how exactly does drought kill trees? A child easily grasps that lack of water will kill about any plant. But the specific biological mechanism by which trees die from drought has not been well-established. It's the difference between knowing that shooting someone in the chest will kill them, and understanding why a bullet puncturing the heart will end a life.

A team of scientists, led by Dr. William Anderegg of Princeton, have been working on the aspen question, and their results were published today in Nature Geoscience. The answer is something called "xylem cavitation." And unless we do something big about climate change soon, it will kill most of the aspens in the Southwest.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Here's what that means. Trees transport water through their xylem tissue (one example of which is regular old wood), basically composed of millions of tiny tubes, or "conduits." Xylem doesn't work like a mechanical pump — instead, water flows up the tree trunk through capillary action. That flow is maintained through evaporation at the leaf surface, removing water at the top so more can replace it, and supplied by the roots drawing water from the soil.

In hot, dry conditions, like the early 2000s drought, water evaporates more quickly from the leaf surface — and there is less water in the soil to maintain supply. Anderegg and his team quantified both of these with a factor they called "climatic water deficit." When the deficit is high, the water pressure inside the xylem decreases due to tension between the top and bottom of the tree.

If the pressure gets low enough, gas bubbles will spontaneously form in the water column — which is called cavitation. A bubble instantly blocks that particular xylem conduit and prevents the water from flowing. Block enough conduits, and the tree desiccates and dies.

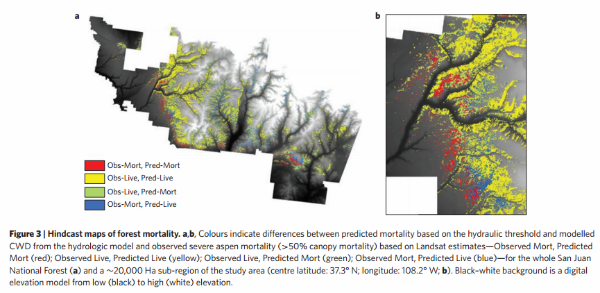

It's "like a tree heart attack," says Anderegg. He and his team constructed a model of this cavitation mechanism, calculated a threshold at which aspens should die, and compared it with historical data on the early 2000s drought. They found pretty clear agreement, explaining about 75 percent of the tree mortality during that time (a good result, given how complex forests are). In this image, red and yellow represent when the model correctly predicted whether a tree would live or die, while green and blue are the corresponding wrong predictions:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Xylem cavitation has been understood for years, but this is strong evidence for this being the murder culprit, so to speak. (Note that this model only applies to deciduous tree species. Conifer species like lodgepole pine have also been killed en masse by climate change-fueled drought, but abnormal beetle swarms are what strike the killing blow.) Others had suggested different mechanisms, like starvation. What's more, this threshold model has some disturbing implications. All that is required to kill an aspen forest is a sufficiently hot and dry spell.

According to the big climate models, under a high-emission pathway (that is, assuming world society does little to combat climate change), large sections of current aspen forests will be consistently above the mortality threshold by the 2050s. But since all that is needed to kill an aspen tree is a couple of exceptional years, then the bulk of current aspen forests will likely be dead some time before that decade.

This matters not just for the aesthetic value of forests in themselves, but also for many human interests as well. Besides being a major tourist attraction — they're just about the only fall color in much of the Colorado mountains — aspen is a major commercially harvested species in the Southwest. Aspens also support a large variety of local wildlife, much of it important to local economies, and a variety of other ecosystem services (like water filtration).

Obliterating the aspens would not only be a great ecological crime, but also a terrific blow to local communities across the Southwest.

Therefore, the drought of the early 2000s was a "canary in the coal mine," says Anderegg. If we do nothing about climate change, then by 2050 the average year will be about like 2002 in terms of temperature and precipitation. The aspens, and everything that relies on them, will be dead.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

Are zoos ethical?

Are zoos ethical?The Explainer Examining the pros and cons of supporting these controversial institutions

-

Will COVID-19 wind up saving lives?

Will COVID-19 wind up saving lives?The Explainer By spurring vaccine development, the pandemic is one crisis that hasn’t gone to waste

-

Coronavirus vaccine guide: Everything you need to know so far

Coronavirus vaccine guide: Everything you need to know so farThe Explainer Effectiveness, doses, variants, and methods — explained

-

The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.

The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.The Explainer Wildfires are forcing people from their homes in droves. Where will they go now?

-

Coronavirus' looming psychological crisis

Coronavirus' looming psychological crisisThe Explainer On the coming epidemic of despair

-

The growing crisis in cosmology

The growing crisis in cosmologyThe Explainer Unexplained discrepancies are appearing in measurements of how rapidly the universe is expanding

-

What if the car of the future isn't a car at all?

What if the car of the future isn't a car at all?The Explainer The many problems with GM's Cruise autonomous vehicle announcement

-

The threat of killer asteroids

The threat of killer asteroidsThe Explainer Everything you need to know about asteroids hitting Earth and wiping out humanity