The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.

Wildfires are forcing people from their homes in droves. Where will they go now?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

California, Oregon, and Washington are on fire.

At least 33 people have died in recent days, and more than 5 million acres have been scorched as out-of-control blazes rage across the American West. The 2020 wildfire season in California is already the most destructive in the state's history — exceeding the record set in 2018, which in turn beat the record set in 2017. Experts agree that rising temperatures from climate change have turned much of the region into dry kindling, ready to spark in an instant.

"This is a climate damn emergency," California Gov. Gavin Newsom said last week.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Disasters like these displace people. Tens of thousands of fire survivors have been forced to flee their homes, and more than 500,000 — half a million — Oregonians have been warned they might soon be ordered to leave. In the meantime, many evacuees are sheltering "in an assortment of RVs, cars, and tents." Many do not know if their homes will still be standing when they try to return, or where they will go if those houses are indeed destroyed. The fires will eventually end, but for many residents of the region, the disaster is just beginning.

The climate refugee crisis has come to America.

We're not used to thinking of that crisis as an internal American problem. Publicly, at least, officials and experts have often focused on how poorer countries will deal with the migration of people fleeing drought, floods, devastating storms, and other disasters — both fast- and slow-moving — caused by rising temperatures across the globe. In 2018, a World Bank report estimated that Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia would spawn more than 143 million "climate migrants" by 2050.

"The developed world is still largely sheltered from climate change effects," one expert wrote in 2016. "But the world's poor feel the impacts directly."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

America's Pacific Northwest surely counts as part of the "developed world." So does Miami, which earlier this year was identified as "the most vulnerable major coastal city in the world" thanks to rising seas brought on by the changing climate. Same goes for Iowa, where climate-aided flooding devastated much of the state last year.

In fact, climate migration was already well underway in the United States before the latest round of fires. The Urban Institute estimates more than 1.2 million Americans left their homes in 2018 for climate-related reasons — some were escaping long-term problems, but others were fleeing short-term disasters that became permanent displacements. Sea level rise could force millions more coastal residents to move in coming years. People won't keep living in places where it is impossible to live. Sooner or later they will choose — or be forced — to leave their homes and find somewhere safer.

The response from the Trump administration to international refugees has been to hang a "keep out" sign at the nation's borders, all but snuffing out the torch on the Statue of Liberty. But it's impossible to do that to fellow citizens. That doesn't mean climate migration won't create domestic tensions. A U.N. human rights expert last year warned of a coming era of "climate apartheid," where "the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger, and conflict while the rest of the world is left to suffer."

America, already plagued with "Gilded Age" levels of economic inequality, probably won't be immune to that dynamic. Urban Institute's Carlos Martin points out that many communities are unready to host an influx of climate refugees. "Consequently, newcomers are perceived as competitors for jobs and housing — especially where these were already tight," he writes. "Existing financial and health service providers become overwhelmed and often underresourced for the specific needs of the migrants. Particularly when newcomers differ by race and income, they are increasingly and inaccurately blamed for all kinds of problems."

One obvious answer to these challenges is to finally get serious about mitigating climate change. The Trump administration didn't cause the climate problem, but it seems hellbent on opposing any action to stop it — the president pulled the United States out of the Paris Accord, and has rescinded regulations to curtail greenhouse gases emissions. The administration just hired a climate denier for a top position at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. As is so often the case with this presidency, states, local communities, and individuals are being left to figure out for themselves how to respond to another "damn emergency" that won't go away on its own.

The evacuees fleeing the American West are giving America a glimpse into its future, but also its past. Hurricane Katrina created its own diaspora of New Orleans residents, thousands of whom fled the city and never returned. Before that, during the "Dust Bowl" days of the 1930s, hundreds of thousands of Oklahomans fled drought and Depression to start a new life elsewhere.

Many of them ended up settling in California.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Africa could become the next frontier for space programs

Africa could become the next frontier for space programsThe Explainer China and the US are both working on space applications for Africa

-

Why does the US want to put nuclear reactors on the moon?

Why does the US want to put nuclear reactors on the moon?Today's Big Question The plans come as NASA is facing significant budget cuts

-

US won its war on 'murder hornets,' officials say

US won its war on 'murder hornets,' officials saySpeed Read The announcement comes five years after the hornets were first spotted in the US

-

Why the Moon is getting a new time zone

Why the Moon is getting a new time zoneThe Explainer The creation of 'coordinated lunar time' is part of Nasa's mission to establish a long-term presence on Earth's only natural satellite

-

'Extremely dangerous heat wave' to scorch parts of US

'Extremely dangerous heat wave' to scorch parts of USSpeed Read

-

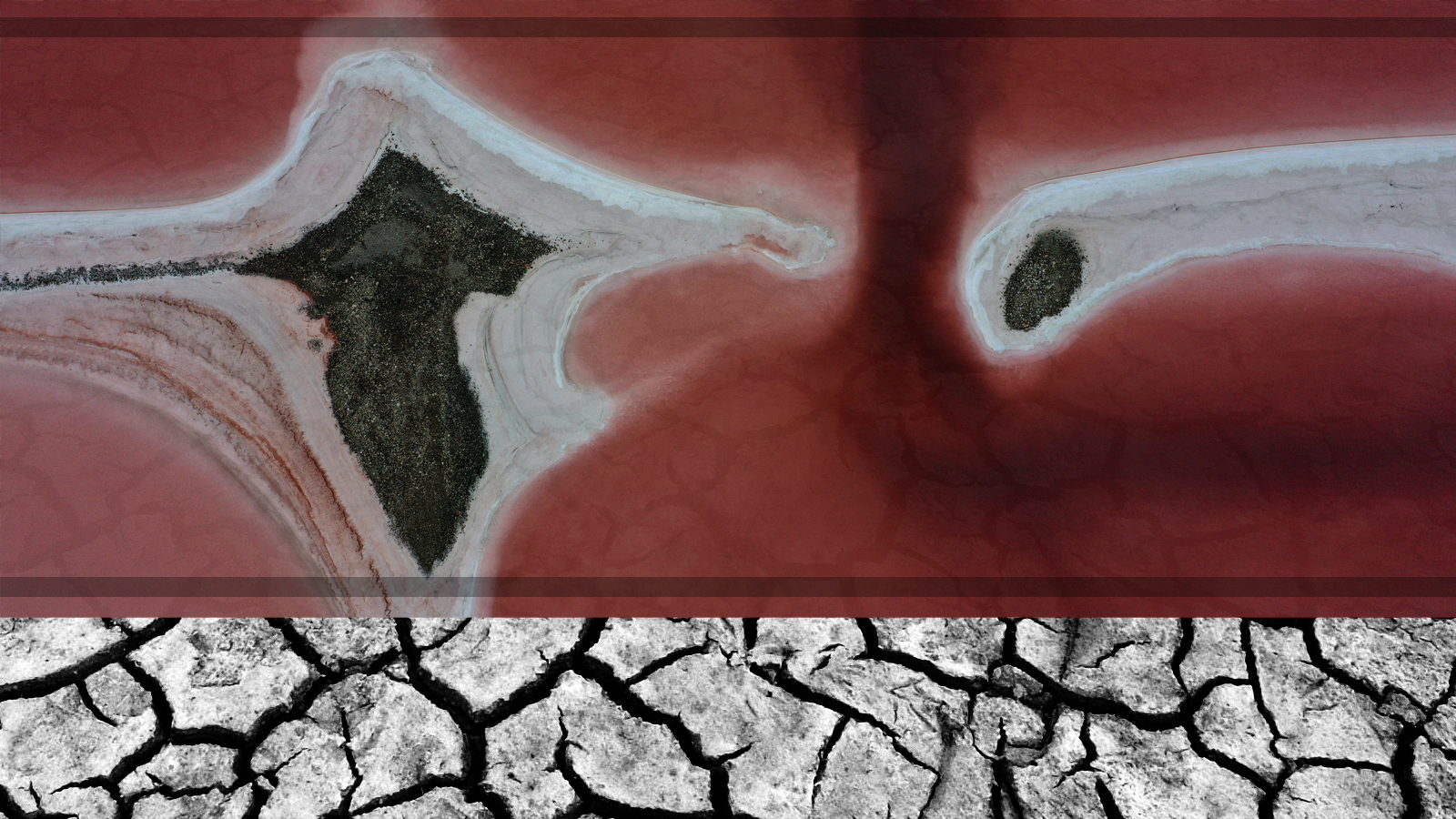

Saving America's salt lakes, great and small

Saving America's salt lakes, great and smallSpeed Read The Great Salt Lake is disappearing, leaving behind a 'Great Toxic Dustbowl'

-

Arctic front brings life-threatening temperatures to Northeast

Arctic front brings life-threatening temperatures to NortheastSpeed Read

-

Are zoos ethical?

Are zoos ethical?The Explainer Examining the pros and cons of supporting these controversial institutions