Baltimore, and America's double standard on violence

The media is quick to forget that white violence has been a recurring feature of American history

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Monday in West Baltimore, following the funeral of Freddie Gray, who died of a spinal injury sustained in police custody, there was a large peaceful protest. Afterwards, a smaller number of people rioted. Looters trashed a CVS and a check-cashing joint, while others burned down a couple police cars. Fifteen officers and an unknown number of protesters were injured, with roughly 200 people arrested. School was closed Tuesday, and a one-week curfew was imposed.

Riots are always an interesting time to observe the mainstream press, because it's often when the mask of "objectivity" slips, and anchors and pundits slip into blatant editorializing. On CNN, Wolf Blitzer was stunned and outraged that the police weren't there to protect property. Don Lemon grilled the Maryland governor and Baltimore mayor over their insufficient aggressiveness in confronting the riot. Even David Simon, the creator of The Wire, told rioters to "go home."

Perhaps the best summary of this worldview came from Howard Kurtz, the media correspondent for Fox News, who wrote a tweet simultaneously bemoaning the rioting while implicitly absolving the police of wrongdoing for Gray's death:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

To be fair, he later clarified that the police shouldn't be presumed innocent. But the ideology on display, which reflects a larger one that reaches beyond the media, goes something like this: America is a basically decent place. The institutions of public authority, particularly the police and the military, deserve the overwhelming benefit of the doubt. Thus, any instance of police violence is presumed justified unless there is unquestionable evidence to the contrary — and instances of violence against the social order, as seen in Baltimore, are absolutely beyond the pale.

But when considered in the light of history, this view is not just unfair but ridiculous.

These days, riots are almost universally associated with black urban communities. But before the 1960s, "race riots" meant white riots, almost universally directed against blacks. Whether it was competition for jobs (Cincinnati: 1841), resentment at black veterans (Memphis: 1866; many cities: 1919), paranoia over black sexuality (Atlanta: 1906), or resentment at blacks moving into white communities (Detroit: 1943), American whites have historically needed little excuse to conduct mob violence against African-Americans.

This violence was not random or accidental. It was part of the American system of racial domination. It was not a coincidence that when a riot got going in 1921 in Tulsa, white mobs, assisted by local authorities, proceeded to loot and torch the entire black district of Greenwood — then the richest black community in the nation — burning over 1,200 homes and killing dozens.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

More generally, as Hamden Rice points out, semi-random psychotic violence against black men was the keystone institution of Jim Crow. It was what kept blacks in terrified submission, lest they be lynched on the slightest (or no) pretext.

Judged by its own racist objectives, we must admit this violence was a huge success, though it was not the only part of white supremacy. Blacks were kept as a subordinate caste. What wealth they managed to build up was largely stolen or destroyed. They were kept from living in white neighborhoods.

That kind of white riot doesn't happen anymore — today's white riots are usually about sports or pumpkins. But their legacy, along with that of extensive racist government policy, are still with us today. Indeed, white riots were a key factor in the creation of black ghettos. As the Kerner Report, which studied the causes of the race riots of 1967, put it: "White society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it."

The long history of white rioting does not in itself justify a black version, of course. Tactical questions will always be different for a minority fighting state oppression. Martin Luther King made a good case for disavowing riots as poor tactics that give the white community an escape from guilt.

At any rate, the issue at hand is the golly-gee "America Is Good" lens through which so much mainstream commentary is unthinkingly framed, as if a relatively small riot is a huge deviation from the historic norm of strict non-violence. It's not just historically blinkered but also blind to current events. Freddie Gray's death was only the most recent controversy for a police department that routinely brutalizes its black residents:

Over the past four years, more than 100 people have won court judgments or settlements related to allegations of brutality and civil rights violations. Victims include a 15-year-old boy riding a dirt bike, a 26-year-old pregnant accountant who had witnessed a beating, a 50-year-old woman selling church raffle tickets, a 65-year-old church deacon rolling a cigarette and an 87-year-old grandmother aiding her wounded grandson. [Baltimore Sun]

That goes double for when King himself is inevitably trotted out as the only legitimate example of protest. MLK was nonviolent, why can't these people be? As Ta-Nehisi Coates notes, it's a question seldom asked of the police.

King was one of those rare Americans — someone who actually hewed to Christ's dictum that "if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also." And since this apparently needs to be said, King's nonviolent tactics were quite successful in breaking the back of Jim Crow terror, but they did not stop him from being murdered in cold blood.

So for those who wish to stop riots, police brutality might be a good place to start. More ambitiously, one could tackle the grinding poverty of Gray's neighborhood in Baltimore, where unemployment is 20 percent and over a quarter of the buildings are vacant.

But Americans, I fear, are most interested in forgetting our dark past.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Gunman kills 6, himself at Colorado Springs birthday party

Gunman kills 6, himself at Colorado Springs birthday partySpeed Read

-

Columbus police fatally shoots Ma'Khia Bryant, 16, quickly releases body-cam footage

Columbus police fatally shoots Ma'Khia Bryant, 16, quickly releases body-cam footageSpeed Read

-

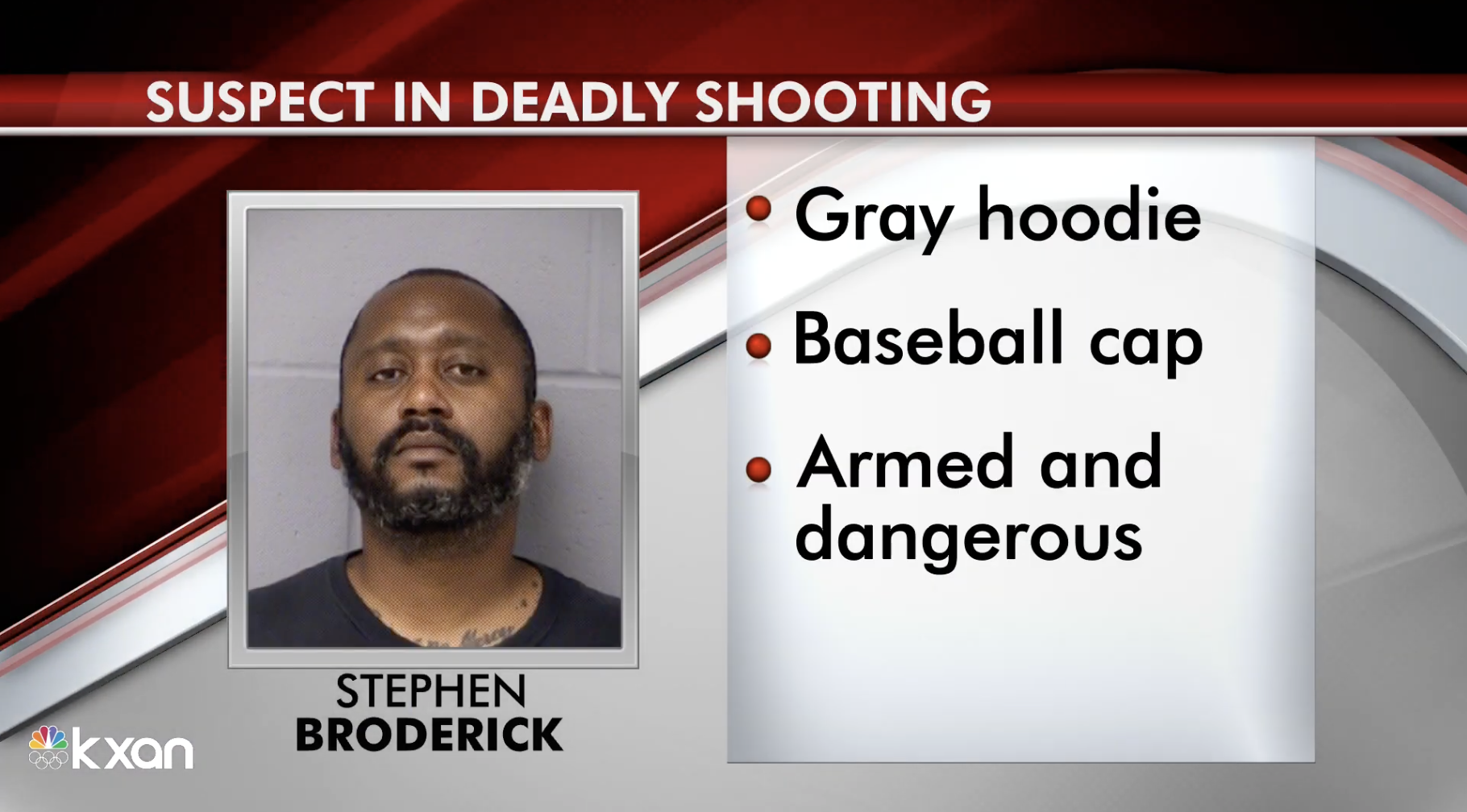

Austin police, feds searching for ex-sheriff's deputy accused of killing 3, in Sunday's 2nd mass shooting

Austin police, feds searching for ex-sheriff's deputy accused of killing 3, in Sunday's 2nd mass shootingSpeed Read

-

At least 8 dead in Indianapolis FedEx shooting

At least 8 dead in Indianapolis FedEx shootingSpeed Read

-

Scalise says GOP will 'take action' on Gaetz if DOJ moves ahead with 'formal' case

Scalise says GOP will 'take action' on Gaetz if DOJ moves ahead with 'formal' caseSpeed Read

-

Watchdog report: Capitol Police knew about potential for violence on Jan. 6, but held back

Watchdog report: Capitol Police knew about potential for violence on Jan. 6, but held backSpeed Read

-

Former classmate arrested in 1996 disappearance of college student Kristin Smart

Former classmate arrested in 1996 disappearance of college student Kristin SmartSpeed Read

-

Report: Gaetz associate has been cooperating with federal investigators since last year

Report: Gaetz associate has been cooperating with federal investigators since last yearSpeed Read