Inside Europe's migrant crisis

Record numbers of migrants are drowning while trying to flee the Mideast and Africa for Europe. Why do they keep coming?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How many people are dying?

Since January, an estimated 1,750 migrants have drowned trying to reach Europe via boat — a greater death toll than the Titanic's. Hoping to escape the war, poverty, and violence of their own countries in Africa and the Middle East, these desperate refugees pay up to $2,000 each for a spot on one of the overloaded, rickety fishing vessels or rubber dinghies crossing the Mediterranean every day. Last year, a staggering 215,000 migrants successfully reached Europe, most landing in Italy. Italy sent only 5,000 home; the rest disappeared into the Continent, with many headed to Northern Europe in search of work and better lives. But often these voyages end in a tragedy — such as the April 19 disaster, in which about 900 refugees drowned en route from Libya. With another million migrants reportedly waiting in Libya to cross the dangerous seas, the United Nation's High Commissioner for Human Rights has warned that European leaders must do something to stem the crisis — or they "risk turning the Mediterranean into a vast cemetery."

Where are the boats coming from?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

About 80 percent of migrants set sail from the failed state of Libya, where a multimillion-dollar smuggling business has sprung up in the chaotic aftermath of the 2011 revolution. Last year, a vast network of Libyan militias collaborated with Italian crime syndicates to make an estimated $170 million in people smuggling. The traffickers exploit migrants who have traveled more than 1,000 miles from countries as diverse as Niger, Iraq, Somalia, and Eritrea to start a new life. An estimated 31 percent are from Syria, driven away by a horrific civil war. "These are the most desperate people," says Flavio Di Giacomo, from the International Organization of Migration. They know the voyages are perilous, but are stuck "between hell and the deep blue sea."

Why do so many boats sink?

To maximize their profits, smugglers pack masses of migrants into cheap, barely seaworthy boats. In last week's tragedy, the 900 migrants were crammed into a 66-foot wooden fishing boat. When too many passengers lean on one side of those ramshackle vessels, they capsize. Even worse, hundreds of poorer African migrants are often locked into the boat's teeming hold for crowd control. So if the ship goes down, they have no choice but to go down with it. Sometimes, smugglers put migrants on a boat with no captain, hand them a compass, and tell them to find their own way to Europe. Rescue boats save some of these lost vessels, but many wind up sinking or capsizing. The death toll has grown astronomically since the demise of Operation Mare Nostrum last November.

What's that?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Mare Nostrum (or Our Sea) was an Italian naval rescue operation, launched after 300 people drowned off the Italian island of Lampedusa in October 2013. At a monthly cost of $9.7 million, Italian rescue boats trawled the Mediterranean looking for migrants in distress — ultimately saving and bringing back to Italy more than 140,000 refugees in a single year. But the operation fell victim to political opposition: Italian lawmakers claimed migrants were using the rescue boats as a taxi service, and called on the EU to help fund the costly program. Instead, European leaders axed the operation altogether.

Why did Europe back out?

Britain was one of many countries that claimed Mare Nostrum was creating an "unintended ‘pull factor'" for migrants: If they knew there was a good chance they'd be rescued, they were more likely to risk the journey. The EU instead embraced a new "Fortress Europe" approach, tightening the borders and launching the limited Triton program, which only searches the waters within 30 miles of Italy's coastline. But Triton has done nothing to drive down migrant numbers, which remain as high as in 2014, when about 26,000 refugees crossed over in the first four months of the year. The only thing that's changed is the number of deaths, which has multiplied 30 times. By April 21 in 2014, 56 people had died. This year by that date, 1,727 had. "When Operation Mare Nostrum was cut, we said it would be a death sentence," says Save the Children's Gemma Parkin, "and it has been just that."

What's the solution?

Facing an international outcry after last week's disaster, EU leaders cobbled together a "10-point plan" that triples Triton funding and pledges to destroy smugglers' boats in Libya. But many migrant advocates argue the plan doesn't go far enough. Some European lawmakers are for adopting Australia's controversial approach (see below). Human rights experts argue that the crisis will exist as long as Middle Eastern and African countries remain in chaos. Instead of treating these migrants like criminals, they say, Europe should provide safe migration routes. But European nations say they are already struggling to absorb the hundreds of thousands of migrants who have already landed on the Continent's shores. "We're swamped," says Italy's minister for European affairs. "There's not even enough space in Sicily's cemeteries to bury the dead."

Australia's closed-door policy

When a wave of Iraqi and Afghan migrants set sail for Australia five years ago, lawmakers Down Under responded by adopting one of the world's harshest border policies. There would be absolutely no resettlement of migrants, the Australian government announced. Instead, the migrants would be towed back to the Indonesian ports they'd set off from, or imprisoned in detention centers in remote Papua New Guinea before being shipped to destinations such as Cambodia. On the surface, the policy has worked: Since 2013, only 16 migrant boats have attempted the journey to Australia. But migrant advocates argue Australia hasn't "stopped the boats" at all. "What Australia has done is just displace the issue away from the shores of Australia" and toward the Mediterranean, says Paul Power of the Refugee Council of Australia. "They have almost without doubt made the situation worse for people who have tried to find safety in Europe."

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

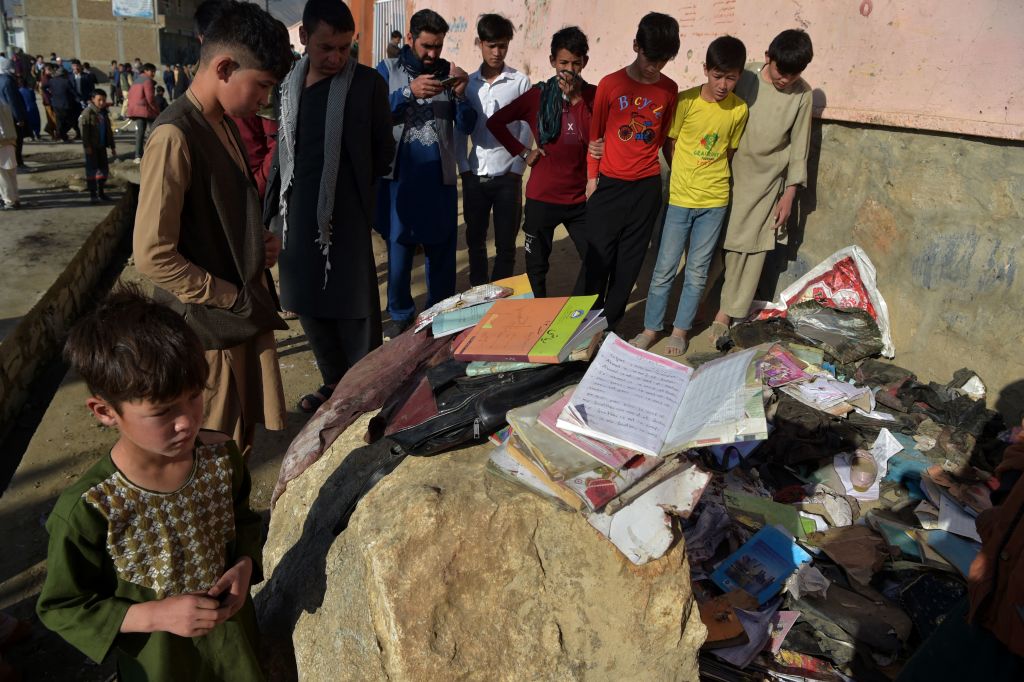

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

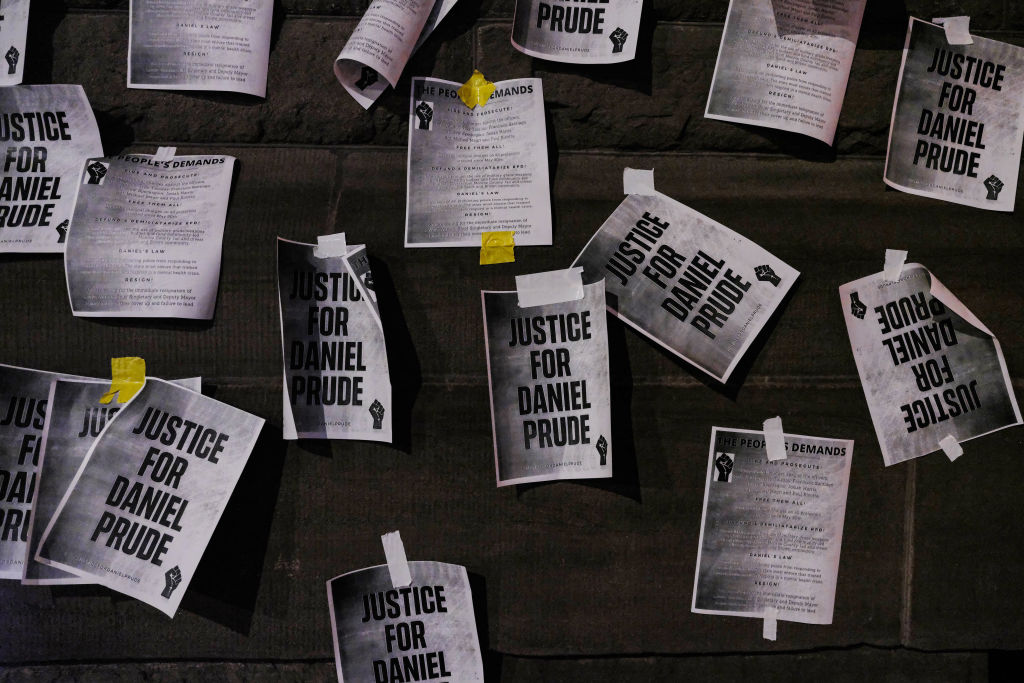

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

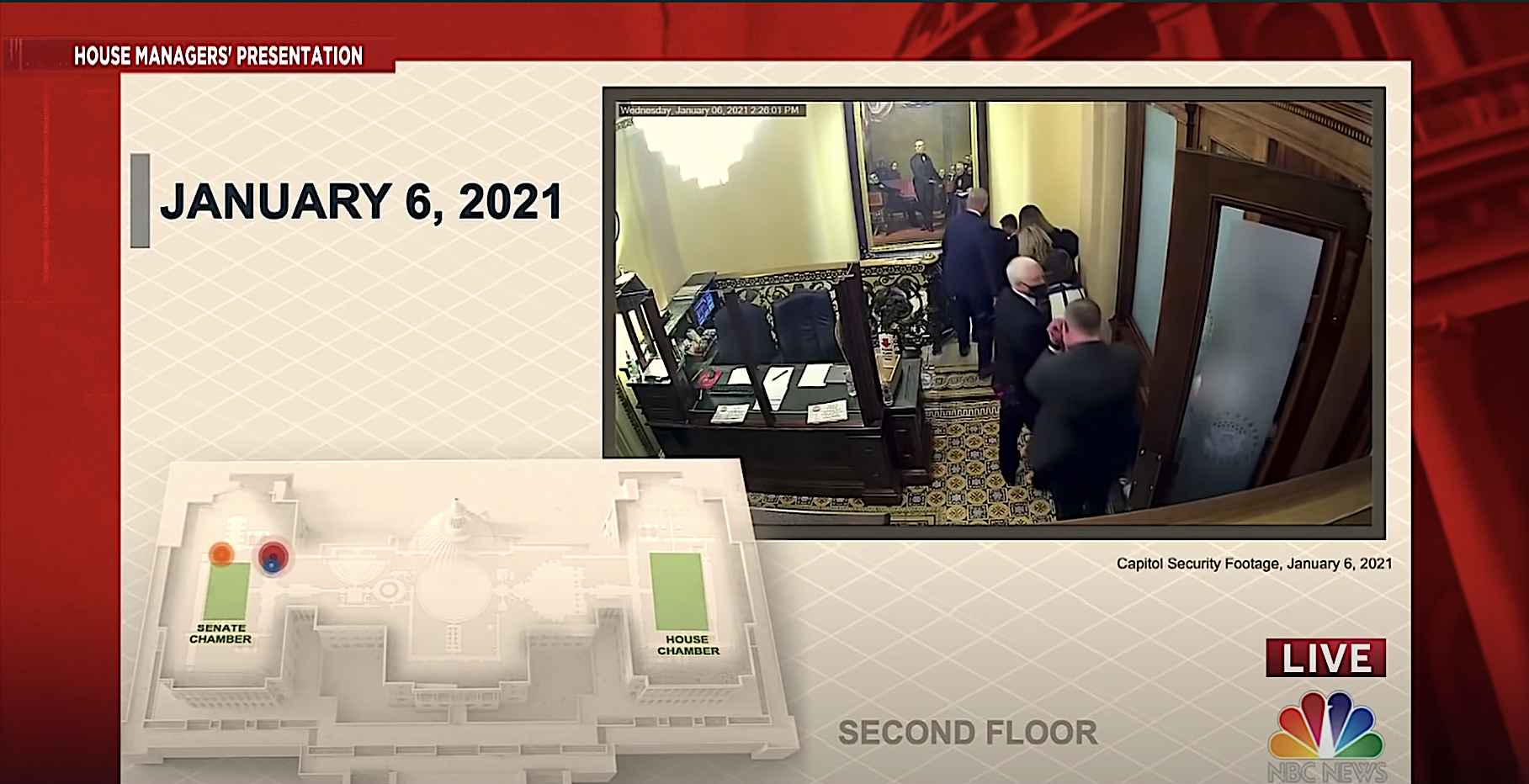

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read