Caitlyn Jenner says she's a Christian. What does that mean for Christianity?

Can Christianity accommodate the likes of Jenner?

It's been a week and a half since we began to digest the news (and image) of Bruce Jenner's transformation into Caitlyn, and the conversation has just started to get really interesting.

Did you know that Jenner considers herself a Christian (in addition to voting Republican)? It's true. And that fact has sparked a fascinating debate among a group of thoughtful pundits.

The Economist's Will Wilkinson began the discussion by taking Jenner at her word. She's a Christian — a distinctively American kind of Christian.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The tolerant Jesus of…Ms Jenner may not be the Jesus of Thomas Aquinas or Martin Luther or John Knox or John Wesley. He is a Jesus perhaps more thoroughly invested in the "autonomous eroticized individualism" of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman than any first-century reinterpretation of the Judaic law. But that is the American and still-Americanizing Jesus of many millions of believers who, like Caitlyn Jenner, attend non-denominational evangelical churches…Caitlyn Jenner of Malibu is a leading indicator not of the secularization of America, but of the ongoing Americanization of Christianity… [The Economist]

This passage predictably provoked Rod Dreher, a devout Eastern Orthodox Christian, to decry Christianity's "America problem." Wilkinson is right, Dreher believes, and that points to the need to protect Christianity against further Americanization. Ross Douthat, a Catholic, takes a similar line, while expressing somewhat less pessimism about the inevitable triumph of this gnostic American version of Christianity over more traditional forms of the faith.

There's a lot of truth in Wilkinson's take on Jenner's Christianity. But I wonder if it might overstate the extent to which American culture poses a uniquely inimical threat to orthodox Christian faith and practice. Taking the long view of Christian history, we can see that some of the aspects of contemporary American Christianity that most trouble conservatives can be traced back to Jesus Christ's own words — and that others have taken root because of the fundamental character of the religion founded on his teachings.

Let's start with Christ's words.

As I've argued on more than one occasion, Christ's message is among the most radically subversive ever uttered: The established political and religious orders and hierarchies don't matter, and neither does following the stringent details of the Jewish law; all human beings innately possess equal dignity, from emperors and kings on down to peasants and prostitutes; the last shall be first and the first shall be last; the meek shall inherit the earth. That's as radical and subversive as they come.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Don't believe me? Listen to Alexis de Tocqueville. Or Friedrich Nietzsche. Both thinkers argued with extraordinary power that Christ is the ultimate source of a democratic revolution that has been transforming the world for two millennia now, as Western civilization has worked out the inner logic of the equality Jesus preached in ancient Judea and attempted to apply it more and more strictly to social and political life.

Marrying someone of the same sex, like transforming oneself surgically from a man into a woman, might seem to contradict various dogmas and doctrines of historic Christianity — but advocates for both can still find inspiration in the subversive words and example of Christ himself.

Now, critics of this view of Christ's message can always respond that the interpretation seems to be contradicted by the fact that the institution of the church has everywhere and always opposed same-sex marriage and the transgendered worldview. Christian cultures like our own have, too, until very, very recently. What sense does it make to trace a development that gained significant numbers of champions only within the last few decades to teachings that were uniformly interpreted in the opposite way for 2,000 years?

Good point — but one that skates over a second distinguishing mark of historic Christianity that defenders of orthodoxy often downplay or deny: the religion's incredibly, perhaps uniquely, malleable character.

Of the three monotheistic religions — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — Christianity is easily the most protean. Yes, Judaism and Islam have evolved over time, broken into rival sects, squabbled, and sometimes fought bloody battles over doctrinal and other differences. But at the core of both religions is a scriptural body of divine law — the Torah in Judaism, Sharia in Islam — that seeks to guide the lives of members of the faith in minute detail. Jews and Muslims can debate the meaning of those laws and how to apply them. They can even try to redefine the faith in such a way that the laws matter less or matter in a different way than they previously have. And yet the law remains always somehow at the center of things, as anchor, orientation, inspiration, obstacle, foil.

Christian scripture has no such legal core. It is explicitly founded in a declaration of independence from Judaic law, which Christ claims at once to fulfill and transcend with his ministry, death, and resurrection. Accordingly, his followers are told that the old rules don't matter. What does matter is loving God and one's neighbor, and maintaining a pure heart before the eyes of God. That's it. Except, of course, for a long list of incredibly powerful but also frequently obscure, elliptical parables and seemingly contradictory assertions.

The often cryptic character of Christ's teachings, combined with his emphasis on an extra-legal form of inward purity, made the religion founded in his name extremely adaptable — in the sense that it could take root anywhere and appeal to anyone, but also in the sense that it could mesh and merge with any number of different political systems and cultures. And it did. Which is one reason why the first two centuries after Christ's death were a time of dogmatic and doctrinal chaos in the nascent Christian world — and why the Council of Nicea in 325 set out to define Christian dogma and doctrine once and for all, and to draw bright lines between orthodoxy and heterodoxy (heresy). Historically speaking, one of the most important roles of the Catholic Church ever since has been to uphold those definitions and police those lines, keeping global Christianity from reverting to chaos.

But it's important to recognize that in taking on this role, the church modeled itself on a form of imperial Roman legalism with no warrant at all in the text of gospels. Born of and eventually taking over administrative duties from the Roman Empire, the Catholic Church quickly became an aristocratic institution. The Christian monarchies and aristocracies of medieval Europe developed along parallel (and sometimes competing) hierarchical lines. In this way, a religion founded in an attack upon the authority and privileges of the Jewish high priests became a church claiming far more authority for itself than any Pharisee could have imagined.

Of course, the church took another shape in the Eastern part of the declining Roman Empire, leading to theological, doctrinal, and administrative differences that eventually split Christendom in two. Far more splintering took place with the Protestant Reformation, and again as the church has spread around the globe into the developing world. Over the past century, Christianity has showed itself to be individualist and capitalist in northern Europe and North America, charismatic and quasi-Marxist in Latin America, capable of being synthesized with animism and other traditional forms of religious practice in Africa — and yes, more than a little gnostic in the United States.

Which is the real Christianity?

The Catholic Church naturally wants to continue arrogating to itself the authority to make that determination, and Dreher, Douthat, and many other conservative believers are eager for Rome (or some other authority) to settle the matter, by upholding age-old standards of orthodoxy and heresy. But what if the "Americanization of Christianity" is no less legitimate — no less a plausible transformation of the gospel message — than the Romanization of Christianity that took place in the centuries immediately following Christ's death, establishing the Catholic Church's ecclesiastical authority in the first place?

In that case, the "Americanization of Christianity" would be just the latest in an endless succession of Christianities, each of them as legitimate as the last and the next. As Jesus Christ apparently put it himself, "Wherever two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them."

Even when one of those gathered is Caitlyn Jenner.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

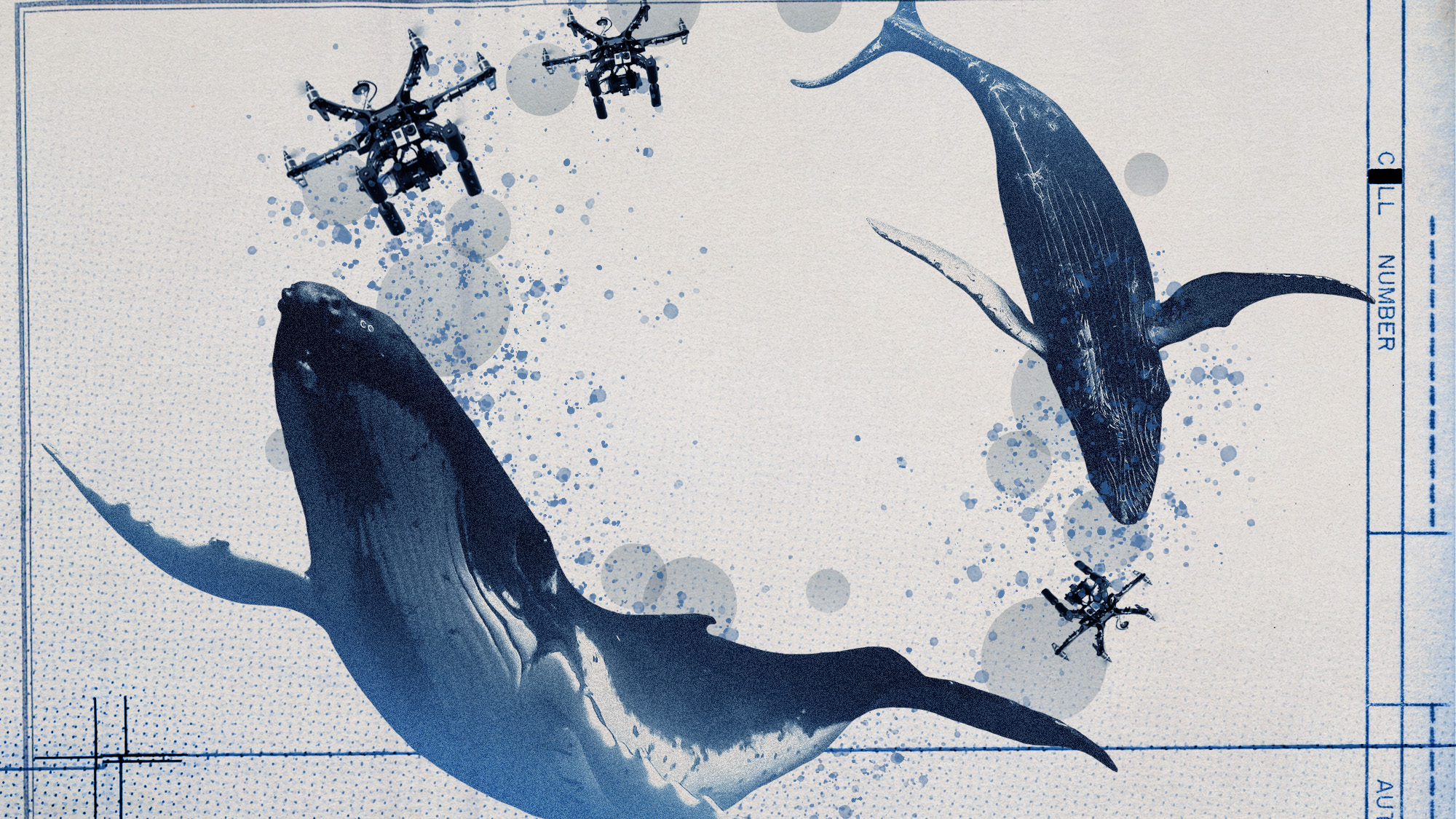

How drones have detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones have detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

A running list of the US government figures Donald Trump has pardoned

A running list of the US government figures Donald Trump has pardonedin depth Clearing the slate for his favorite elected officials

-

Ski town strikers fight rising cost of living

Ski town strikers fight rising cost of livingThe Explainer Telluride is the latest ski resort experiencing an instructor strike