What Libya taught Europe about playing with fire

You'll get burned — again and again

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There is no way around it: The western intervention in Libya was in vain.

Americans, perhaps, have the luxury of feeling sorry for themselves about it. But in Europe, the feelings are of a different order and urgency. According to recent estimates, it is now likely that somewhere between half a million and a million persons will try to cross the Mediterranean this summer.

British authorities, joined in Europe's belated effort to prevent mass drownings, predict 500,000 will leave shore, according to The Washington Post. Libyan officials, reported Voice of America, say one million illegal immigrants alone plan to climb aboard packed smugglers' boats in the weeks and months to come.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For Americans grown used to a dwindling stream of unlawful border crossings from Mexico, the Mediterranean situation is a nightmare of complexity, staggering in scale. Many foreigners are vying not to escape to Europe but to make their way home — to Ghana for instance, from which workers and businessmen looking for opportunity came to Libya's coastal cities in years past, and now find themselves in a long line to trade one humanitarian catastrophe for, quite plausibly, another.

But, of course, U.S. policymakers have not brought themselves to see the problem as their own. Along with their counterparts in the EU, they refuse to pick a side in Libya's chaotic struggle for order among rival militias. The Islamic State, with whom we are allegedly at war, has seized the opportunity to capture Sirte, a strategic city midway between Tripoli and Benghazi that supplies half of all Libyans with electricity.

When President Obama ordered airstrikes against the Gadhafi regime, he did so out of fear that Benghazi's 700,000 residents would be subject to a massacre. But another truth must have been at the back of his mind. As Gadhafi's forces bore down, "Free Libyans" would do what people have done for millennia when confronted with onrushing armies: flee.

It was painfully apparent in March of 2011 that Europe couldn't handle a wave of war refugees hundreds of thousands strong spilling into the EU's weakest, most precarious economies. Now, with Greece on the brink and Italy straining to maintain stability, a wave of "boat people" the size of Benghazi itself would follow a humanitarian disaster with an economic one.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Europe's response has been to bristle. Terrified that Libya will become a sucking wound, drawing in migrants from as far afield as Somalia, Afghanistan, and the imploding nation of Syria, the EU has made concerted preparations for an interdiction force designed to crack down on human smuggling. In a strategy document obtained by The Guardian, planners noted the potential for an intervention on Libyan soil itself, where "heavy military armaments (including coastal artillery batteries) and military-capable militias present a robust threat to EU ships and aircraft operating in the vicinity."

To state the obvious, a poorly led or ad hoc approach to this degree of escalation is certain to end in tears. "It is hard to imagine that these groups will stand by while European militaries operate on their turf," Foreign Policy noted, "even if the targets of EU operations are smugglers rather than militants. The danger of armed action escalating out of control, and leading to further loss of innocent life, is very real."

To be sure, smugglers are profiting handsomely while civilians are dying at sea en masse. Last week, over 2,000 perished, while one smuggler profiled by The Independent boasted a monthly income of $200,000.

But without a full-dress invasion and protectorate in Libya, Europe's half-cocked halfway intervention is most likely to create only greater death and confusion. European leaders know they cannot count on America to bail them out this time around. The duty to lead therefore falls to France, the major power most committed morally and politically to the original Libyan crusade. France will have to take charge to forestall the kind of horror its attack on Gadhafi was designed to prevent.

This is a harsh lesson for Paris. Even more, it is a sobering signal of the new world Europe has finally been plunged into. Crisis does not stop at the eurozone's edge. And despite the continent's unwillingness to meet America's demand to swell its own military budgets, the threat posed by Russia is one that will always draw in the U.S. The tragedy unfolding in the Mediterranean is different. It is Europe, and Europe alone, that will now have to risk acting in vain.

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

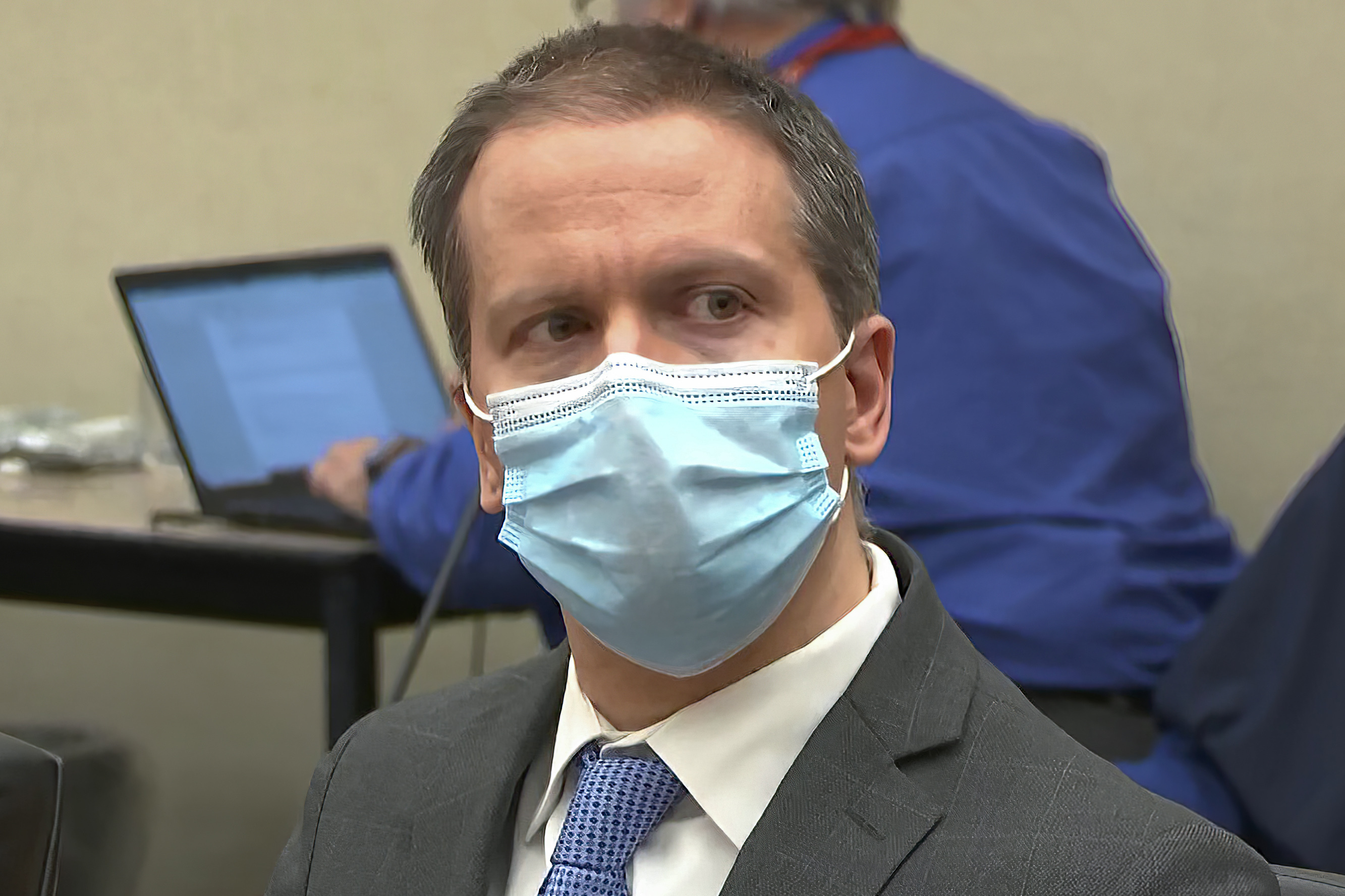

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read