How Big Business teamed with the Supreme Court to destroy the environment

No matter how hard the EPA tries, it always is doing something wrong according to the court

President Obama's most consequential legacy may be his regulation of coal-fired power plants — which is why conservatives have been itching to kill it. On Monday, they got a partial victory thanks to the Supreme Court, which ruled in a 5-4 opinion in Michigan vs. EPA that the EPA did not properly factor in the costs of its new regulations on mercury emissions.

It's an odd decision whose implications are unclear. Though the EPA lost, the regulation itself was not overturned — instead, it was kicked back to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit for a rehearing in light of the latest decision. However, it is a clear indicator that the conservative majority on this court will grasp at very thin straws to obstruct Obama's environmental agenda — and to promote that of Big Business.

The EPA interpreted the Clean Air Act as requiring a two-step process for new regulations: first, a determination that regulation is necessary; second, a construction of the regulatory rule. The EPA argued that explicit examination of costs is properly done during the second step. A collection of industry groups and states sued the agency on this point, arguing that it should have considered costs from the very beginning of the process.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Justice Antonin Scalia wrote the majority opinion, unsurprisingly taking industry's side. Because the Clean Air Act requires the EPA to determine whether a new regulation is "necessary and appropriate," he argued, it must consider costs from the very start of the regulatory process, not just after it has determined whether a regulation is justified.

The logic of this decision is, to say the least, strained. First, as I pointed out with a case concerning New Deal-era price controls last week, the cost question will always be at least partially circular when it comes to regulations that dramatically affect the market viability of coal power. Coal-fired power plants, particularly older ones, were profitable in large part because they had been allowed to pollute the collective commons with mercury (and many other pollutants) without paying for it. Is the money spent on smokestack scrubbers thus a cost, or restitution for decades of theft?

More fundamentally, as Justice Elena Kagan noted in the liberals' dissent, the EPA produces mountains of studies on costs. Indeed, because environmental harms are now a key factor in economic benefit models, the cost question is probably the single most studied factor in EPA analyses.

The initial regulatory finding thus takes place in a context in which future detailed cost studies are assumed — and almost always cannot be done first. "EPA could not have measured costs at the process' initial stage with any accuracy," Kagan writes, because costs will depend totally on the details of the rule, which can't be known beforehand. Scalia's logic would require the EPA to simultaneously produce the regulatory finding and write the rule itself, in a way that might violate the Administrative Procedure Act.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Finally, whether the order was correct or not, the cost studies are already done. One could easily imagine a new regulatory finding being whipped up in 10 minutes by copy-pasting the finished studies finding that the mercury regulation would cost $9.6 billion and provide benefits of between $37 billion and $90 billion. (Scalia sneers at this finding, since it relies mostly on pollutants other than mercury, but does not actually dispute it.) What's more, those numbers are without question an underestimate, since they don't account for the high costs of carbon dioxide pollution.

In other words, as David Roberts writes, it's hard to imagine the actual legal point to this lawsuit. For that, we must look outside the narrow technical questions to the realpolitik of American business regulation. When it comes to new regulations, the American system is a convoluted omnishambles of red tape and legal chicanery. Every important new rule is immediately swarmed by dozens of utterly cynical lawsuits from the affected industries angling to take it down in court, or at least delay it as long as possible.

This decision fits that tradition perfectly. Though the rule has not been overturned, a conservative draw at the D.C. Circuit might finish the job — and until then, the rule will be almost impossible to enforce as it is in legal limbo.

Conservative hacks like Scalia are key in this process. It's the job of big business to come up with convincing legal objections to regulations preventing American children from being stuffed with mercury, and it's Scalia's job as the Supreme Court's #tcot Twitter egg to rubber-stamp their reasoning. Look for his next decision on the EPA, ruling that the agency improperly wrote its rule before the regulatory finding.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

6 exquisite homes for skiers

6 exquisite homes for skiersFeature Featuring a Scandinavian-style retreat in Southern California and a Utah abode with a designated ski room

-

Film reviews: ‘The Testament of Ann Lee,’ ’28 Years Later: The Bone Temple,’ and ‘Young Mothers’

Film reviews: ‘The Testament of Ann Lee,’ ’28 Years Later: The Bone Temple,’ and ‘Young Mothers’Feature A full-immersion portrait of the Shakers’ founder, a zombie virus brings out the best and worst in the human survivors, and pregnancy tests the resolve of four Belgian teenagers

-

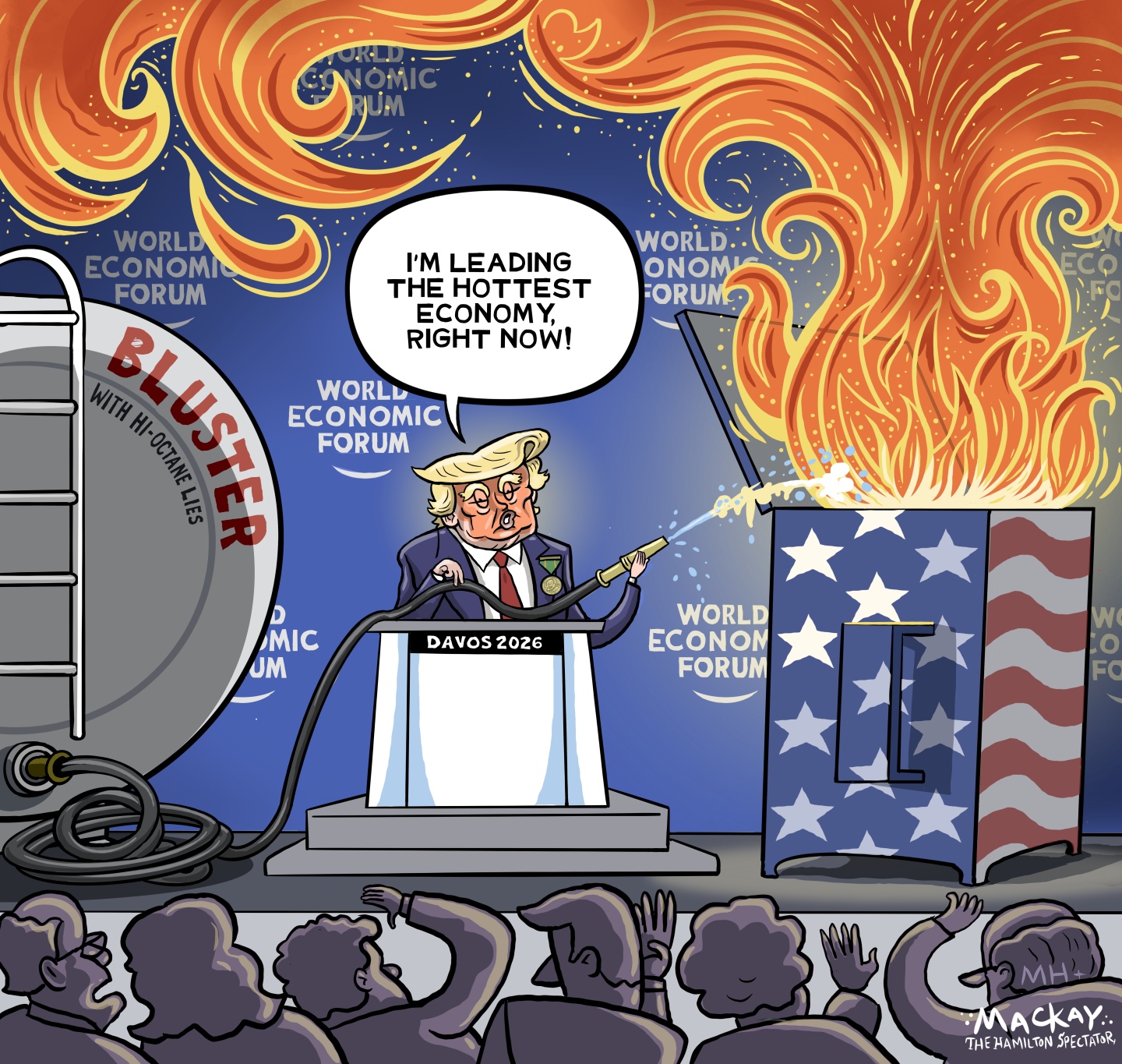

Political cartoons for January 25

Political cartoons for January 25Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include a hot economy, A.I. wisdom, and more