Why privatizing marriage would be a disaster

You simply cannot get government out of the marriage business — and trying will only make things worse

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If Republican presidential candidate Rand Paul is (politically) from Mars, then the leftist feminist writer Naomi Wolf is from Venus. But there's at least one thing this odd couple agrees on here on Earth: The government should get out of the marriage business.

Following the Supreme Court's gay marriage ruling, Sen. Paul argued that Southern states that want to stop issuing marriage licenses were right. The government shouldn't "confer a special imprimatur upon a new definition of marriage," he said. It should leave marriage to churches and temples, regardless of how these institutions define marriage, and let consenting adults of all sexual proclivities write their own civil union contracts.

Likewise, along with fellow liberals such as Michael Kinsley and Alan Dershowitz, Wolf opined some years ago that "dress and flowers" blind women to the reality that, at root, marriage is a "business contract" that the government should stay out of.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Today, the idea of privatizing marriage is gaining popularity. But it is an incoherent concept that, if anything, will actually increase — not decrease — government interference in marriage.

At the most basic level, even if we can get government out of the business of issuing marriage licenses, it still has to register these partnerships (and/or authorize the entities that perform them) before these unions can have any legal validity, just as it registers property and issues titles and deeds. Therefore, government would need to set rules and regulations as to what counts as a legitimate marriage "deed." It won't — and can't — simply accept any marriage performed in any church — or any domestic partnership written by anyone. Suppose that Osho, the Rolls Royce guru who encouraged free sex before getting chased out of Oregon, performed a group wedding uniting 19 people. Would that be acceptable? How about a church wedding — or a civil union — between a consenting mother and her adult son? And so on — there are innumerable outlandish examples that make it plain that government would have to at least set the outside parameters of marriage, even if it wasn't directly sanctioning them.

In other words, this kind of "privatization" won't take the state out of marriage — it'll simply push its involvement (and the concomitant culture wars) to another locus point.

Furthermore, true privatization would require more than just getting the government out of the marriage licensing and registration business. It would mean giving communities the authority to write their own marriage rules and enforce them on couples. This would mean letting Mormon marriages be governed by the Church of the Latter Day Saints codebook, Muslims by Koranic sharia, Hassids by the Old Testament, and gays by their own church or non-religious equivalent. Inter-faith couples could choose one of their communities — but only if it allowed interfaith marriages. But here's what they couldn't get: a civil marriage performed by a Justice of the Peace. Why? Because that option would have to be nixed when state and marriage are completely separated.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This would mean that couples would be subjected to community norms, many of them regressive, without any exit option. For example, a Muslim man could divorce his Muslim wife by saying "divorce" three times as per sharia's requirement and leave her high-and-dry with minimal financial support (this actually happens in India and elsewhere). Obviously, that would hardly be an advance for marriage equality. The reason calls to "abolish marriage" — to quote liberal columnist Michael Kinsley — lead to such absurd results is that they are based on a fundamental misconception about the function marriage serves in a polity.

Cato Institute's Jason Kuznicki notes that marriage, properly understood, is a negative, pre-political right that in the liberal understanding of things the government doesn't grant, it guarantees. It makes as much sense, therefore, to abolish marriage in the name of unshackling it from the government's clutches as it would to, say, abolish property rights to "free" them from the government.

Just as property rights (at least in principle) establish the scope and limits of state power over an individual, marriage does something similar for couples. It basically establishes their right to jointly own property and inherit it from each other, keep and raise their children, and make medical decisions for the other when one is incapacitated. The government can't grab their children or their property without a compelling interest — and it must prevent others from doing so as well. For example, in-laws can't simply take away children because they think their daughter-in-law is an unfit mother or overrule her end-of-life decisions for their son. Couples can voluntarily — and jointly — cede some of their authority to others in special circumstances. But marriage creates a default presumption of their rights — as well as their responsibilities: For example, just as no one can take away their children, they can't abandon their kids either.

Without marriage, every aspect of a couple's relationship would have to be contractually worked out from scratch in advance. This may — or may not — prove to be an onerous inconvenience (some people speculate that companies would start marketing canned contracts to couples). But without licenses or registration for marriages, many things, including establishing paternity, would get really messy. When a couple is in a recognized marriage, the children in their custody are presumed to be theirs — either because they bore them or adopted them.

Privatizing marriage, maintains Kuznicki, would mean giving up this presumption. This would create havoc, especially if a marriage breaks up. "[You'd] get a deluge of claims and counterclaims about child custody and paternity, as parents fought either to establish or relinquish custody without any clear advance guidance from the government about how they will be treated," he insists. "It is hard to imagine the state being more in a private family's business than this." This is not mere speculation. Partly to avert such problems and ensure that children are taken care of, pre-liberal communities that govern marriage by religious norms give a great deal of say to family, neighbors, and village elders in every aspect of a couple's life.

What all of this suggests is that privatizing marriage can't sidestep the broader questions about who should get married to whom and under what circumstances. In a liberal democracy, those who want to expand the scope of marriage have no choice but to fight — and win — the culture wars by slowly changing hearts and minds, just as they did with gay marriage. There are no cleaner shortcuts.

If they want a different reality, they will just have to move to Mars — or Venus.

Shikha Dalmia is a visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University studying the rise of populist authoritarianism. She is a Bloomberg View contributor and a columnist at the Washington Examiner, and she also writes regularly for The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other publications. She considers herself to be a progressive libertarian and an agnostic with Buddhist longings and a Sufi soul.

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

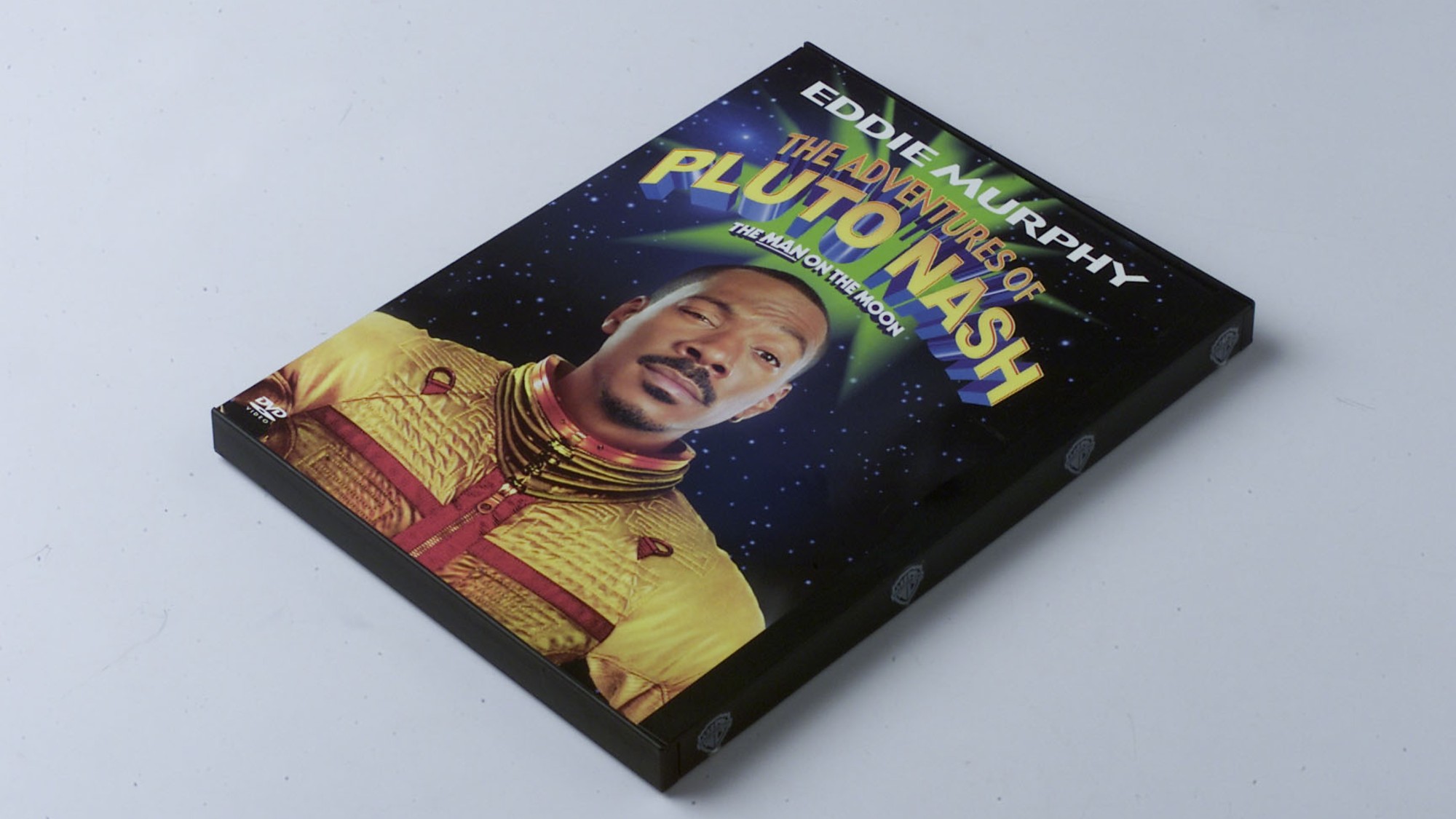

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers