How the obsession over Apple's stock plunge reveals our skewed view of the economy

There's a big difference between what's good for the economy and what's good for investors

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You'd think that Apple's latest earnings report, released Tuesday, would be taken as unalloyed good news: Revenue increased 33 percent and profits increased 38 percent from last year, to $49.6 billion and $10.7 billion, respectively. Not to mention selling 47.5 million iPhones — a 35 percent increase.

But analysts had expected something on the order of 49 million sales. The company moved 1.5 million to three million of its new Apple Watches, below the three million to five million analysts had hoped for. And Apple's revenue slightly missed the $51.13 billion that was anticipated.

The result of those divergences was an 8 percent fall in the value of Apple's shares on the stock market.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Apple Plunge Erases $38 Billion as Product Concern Resurfaces" blared Bloomberg Business. Other headlines included "Apple gives weak forecast, shares fall nearly 7 percent" and "Apple Profit Up 38 percent, but iPhone Sales Disappoint Wall Street." In other words, the global juggernaut's latest numbers were merely "really good" as opposed to "totally #AmazeBalls." So suddenly everyone on the business news beat sees ominous thunderclouds on the horizon.

There are three basic lenses available whenever one is reporting on the world of business and the stock market. One, what's good for society? Two, what's good for the business(es) in question? And three, what's good for investors?

The first lens is a broad and philosophic question that balances how much good you think Apple's products do, versus the damage from its international labor practices, political lobbying, and other matters. There's been plenty written on that, and it need not concern us here.

The tension between the second and third lenses, however, is worth drawing out. Here's what determines the health and sustainability of any given business model: Does it bring in enough revenue — presumably because it provides a socially useful good or service that people are willing to pay for — to pay its workers and management, finance its operations, and maintain its needed capital? In Apple's case, as those topline revenue and profit numbers show, the answer is "hell yes, with plenty of room to spare."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

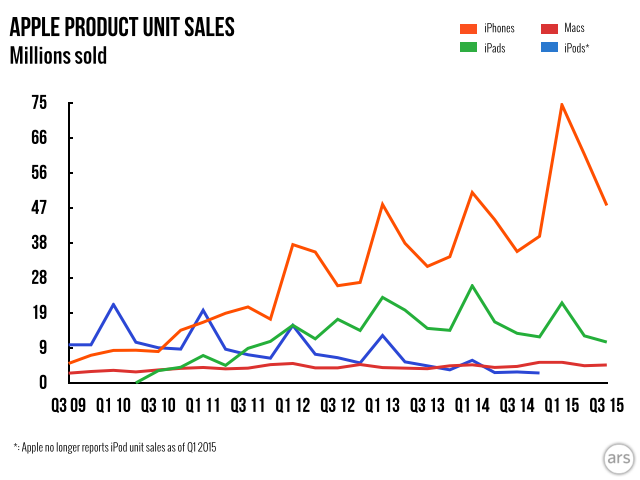

The company's cash reserves are gargantuan. Its laptops are doing modest but steady business, while sales of the iPhone are roaring forward (the regular spikes represent the end of the annual holiday shopping seasons):

(Graph courtesy of Andrew Cunningham and Ars Technica)

Sales of iPods and iPads are trending down, but that's probably because they're being displaced by the iPhone's gangbuster success and latest adaptations.

The role investors play here is they provide equity: They give the company some money, which it can then use to improve its business model. In exchange, the investors get a cut of the company's profits. (Keep in mind profit is just the gravy left over after you take care of all those essential business matters mentioned above.)

Wall Street and the stock market are where investors go to buy, sell, and trade equity, and leveraging differences and trends in equity prices is how investors make their money: Buy when a stock is down, sell when it's up. So how profits perform and how that moves equity markets is understandably their bread and butter, as are good performances that aren't as good as the expectations they may have built into their investment strategy.

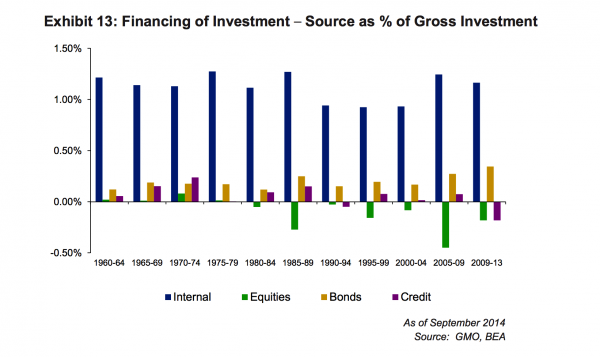

And yet equity is a very small portion of where companies get their financing. In fact, with the rise of the stock buyback revolution, equity has recently become a net drain on the average company's assets.

(Graph courtesy of James Montier, "The World's Dumbest Idea.")

It's certainly possible that equity's importance rises at specific moments in a company's lifecycle. But for the most part businesses finance themselves with debt and their own internal resources and revenue streams. So what investors and Wall Street analysts make of a company's performance really has little to do with whether it's "successful" in any meaningful sense. It's not ideal, but a private, for-profit company can theoretically operate, provide jobs, and remain useful to society in perpetuity, with no profits at all.

All those ominous headlines mentioned above are a function of reporting through the third lens of investor interests. There's nothing malicious about this: Investment and stock trading are perfectly legitimate activities in the economy, and they deserve their own brand of reporting.

But it's instructive to imagine a world in which the journalism that services investors is just another set of trade publications, like those that report on biotechnology or construction. Instead, the interests of investors dominate the business and economics reporting at major outlets like Reuters, Bloomberg, and The New York Times in outsized ways reminiscent of the Times' well-known Style section. The portion of the American population with vested, concrete interests in the subject matter is actually quite small, but it commands massively disproportionate amounts of wealth and power: Almost half of Americans have nothing invested in the stock market at all, roughly two-thirds of what is invested is owned by the top 1 percent, and most of the rest is held by the remainder of the top 10 percent.

You always want to remember that the stock market is not the real economy — and to remember what the first, second, and third lenses actually entail. Disproportionate wealth and power inevitably translates into outsized bullhorns in the culture and media. If the third lens is allowed to subsume the second and the first, our culture and politics might start assuming that whatever's good for the small, rarified population of elite investors is also what's good for American workers and jobs as a whole.

And wouldn't that be a problem?

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.