How the riveting Vidal v. Buckley debates paved the way for an era of idiotic TV punditry

Vidal and Buckley didn't simply want to outsmart each other; they wanted to pummel the other into submission

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This summer, the silver screen has been dominated by microscopic superheroes, prodigious dinosaurs, sexually uninhibited trainwrecks, and gyrating strippers — you know, the usual summertime fare. But the most entertaining film released this summer revolves around something different: a pair of loquacious, Anglo-Saxon intellectuals who wanted nothing more than to extinguish one another on public television.

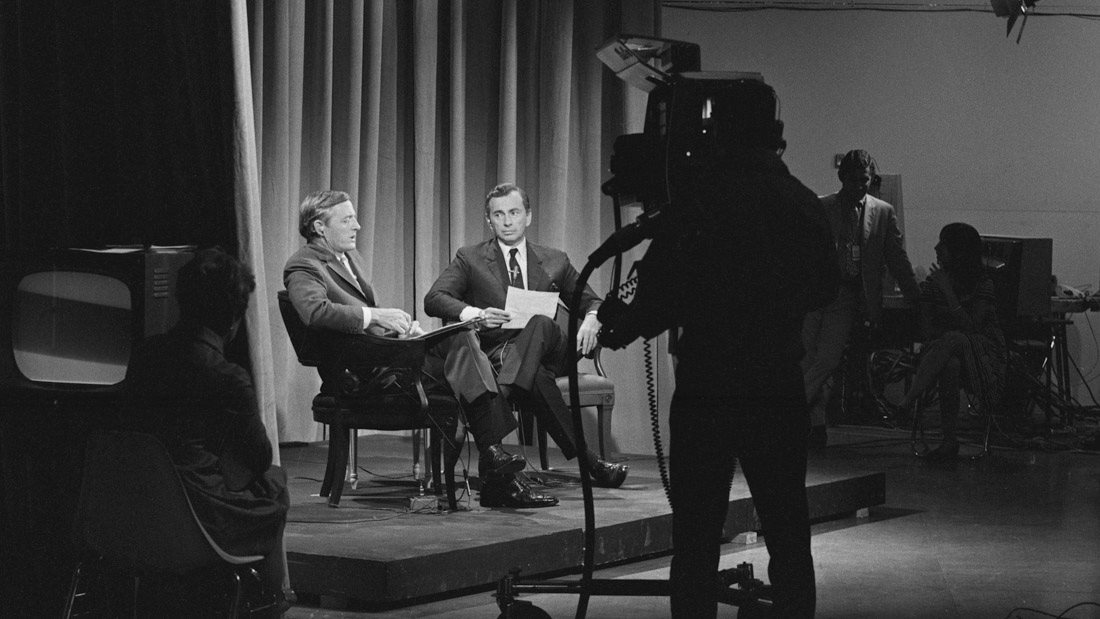

Directed with precision and panache by journalists-turned-documentarians Morgan Neville and Robert Gordon, Best of Enemies begins in the spring of 1968 with a failing network desperate for viewership. With nothing to lose, ABC — dubbed the "budget car rental of television news” by New York's Frank Rich — settled on an unconventional approach to the Republican and Democratic conventions. The plan? Put William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal, two ideologically opposed scholars, in front of a live an audience to do what they do best: debate.

Hailed as the "St. Paul of the conservative movement," Buckley (founder of National Review) served as the voice of the right. Conversely, Vidal, an esteemed author and consummate provocateur, represented the left. As Best of Enemies meticulously documents, this mercenary ploy for higher ratings led to riveting television. For 10 debates, Buckley and Vidal engaged in vigorous, often pointed dialogue about the problems plaguing America, from the Vietnam War to the marginalization of the poor. But the real draw, some might argue, was that these conversations often dovetailed into vindictive ad-hominem attacks. The heated tête-à-têtes weren't just about Richard Nixon, or the overreach of the federal government, or any other hotly contested issue. They were about personal domination. Vidal and Buckley didn't simply want to outsmart each other; they wanted to pummel the other into submission.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Much like Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel's beloved At the Movies, what captured audiences was the visible animosity between the hosts. We are perpetually drawn to drama in all forms — theatrical, personal, and political. Buckley and Vidal were a perfect amalgamation of the three. Their hatred for one another was not manufactured; their mutual disdain burrowed deep inside their respective cores — each believing the other to be emblematic of what was destroying America. Buckley saw Vidal as a "queer pornographer," and Vidal saw Buckley as a mendacious "crypto-Nazi." It was a match made in heaven.

Nearly 50 years later, those ferocious verbal spats translate into thrilling cinema. Well-strung and tightly edited, Best of Enemies rings with a similar epigrammatic wit found in Steven Spielberg's Lincoln. Much like the wig-wearing politicians in Spielberg's masterful biopic, Vidal and Buckley hurl clever retorts and incisive remarks at an incalculable velocity. They were garrulous showmen who abhorred stupidity and aimed to enlighten.

Those debates turned out to be the peaks of both men's public careers. As Best of Enemies moves through time, it makes note of the gradual irrelevance of Vidal and Buckley, as the two radical thinkers were slowly left behind by the culture at large. Yet it's impossible to deny their impact on today's media landscape. By passionately discussing the problems of America, they triggered the dormant desires of a country in search of a public forum. A sort of cultural awakening, spearheaded by two Howard Beale-like figures, occurred on that ABC set in the summer of 1968. The result was a wave of incessant punditry, which now serves as the bedrock for Fox News and MSNBC. Whether it's Bill O'Reilly on the right, or Al Sharpton on the left, the culture is inundated with opinions — all of which are in lockstep with those of their respective political parties.

But Vidal and Buckley eschewed groupthink. They were aristocrats who thought for themselves. When together, they personified what a conversation has the capacity to be. Many have attempted and failed to duplicate their adversarial relationship. The show Crossfire, for example, tried to pit two people — one liberal, one conservative — against each other in the hopes of representing the full political spectrum. What resulted was best described by Jon Stewart, who claimed the CNN program, hosted by two "partisan hacks," was "hurting America."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is not to suggest that lively discourse should be jettisoned. Unfortunately, there's been a perceptible degeneration from Buckley and Vidal to now. Programs on the aforementioned stations spend more time asphyxiating viewers than informing them. In fact, the closest we get to the high-minded repartee of the Buckley/Vidal days is when Stewart appears on The O'Reilly Factor. These episodes, which are infrequent, hint at a show in which two individuals on different sides of the spectrum break bread to talk honestly and openly. Unfathomable as it seems, Stewart and O'Reilly prove that it's possible to step out of the echo chamber we've locked ourselves in.

Today, the most popular cable television programs, according to the Nielsen ratings, are America's Got Talent, Celebrity Family Feud, and NCIS. The abundance of options — coupled with the boom of online streaming services — has made it nearly impossible for there to be a single program everyone voraciously consumes. Vidal and Buckley happened to work in an era where only a handful of stations existed. Now we have a multiplicity of diverse voices, where anyone from anywhere has the potential to attract an audience. So why does it feel like, despite the endless possibilities promised by the internet, there's a paucity of thoughtful debate to be found? Has our collective appetite for edification, for discussion, dwindled?

Perhaps Best of Enemies is romanticizing a time and place all out of proportion. It presents Buckley and Vidal, respectively, as willing avatars for the American public. Whether the rhetoric was angry, progressive, or incendiary, they said what they felt and didn't care who they offended. Save for the satirists like Stewart, John Oliver, and Stephen Colbert, who in the modern media landscape can make that claim?

Sam Fragoso (@SamFragoso) is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in The Atlantic, Vanity Fair, Playboy, NPR, Grantland, and elsewhere. He's also the founder of Movie Mezzanine. A book of his interviews with emerging filmmakers, Talk Easy, will be published by The Critical Press in 2016.