How the TPP boosts corporate power at the expense of national sovereignty

A provision in the massive trade pact makes it easier for multinationals to take nations to court

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) — a massive pact between the U.S. and 11 other Pacific Rim nations that was hammered out this week — has become a major objective of the Obama administration in its final years. If all the nations sign on, it will undoubtedly be a notable part of the Obama legacy, for good or ill.

The deal contains a great many moving parts, the full details of which will not be known until the complete TPP text is made available in a month or so (it was negotiated in secret). However, there is one section of it that is worth examining closely — that of the "lost profits doctrine."

In addition to a section on intellectual property, which could jack up prices for prescription drugs in other countries, the lost profits doctrine is the most dubious part of the TPP. It is found in a provision establishing the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), which provides a method by which corporations can sue governments that are party to the TPP for nationalization or expropriation.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This anodyne-sounding "dispute settlement" mechanism is actually a set of extra-national courts, which will be used solely by multinational corporations to sue governments. When a corporation brings a suit, an ad hoc tribunal is set up to judge the case, and it either awards damages or dismisses it. The system is one-way — nations can't sue corporations under ISDS, and there is no appeal system. (The TPP, it should be noted, is not even close to being the first treaty to establish such a system — over 3,200 existing treaties already have it in one form or another.)

Corporations can generally sue through ISDS under four headings: legal discrimination, denial of justice, the right to transfer capital, and the expropriation of property. It's this last one that is the meat of the issue. Leaked draft chapters of TPP show "expropriation" to include nationalization, seizure, or regulations that could negatively affect the stream of future profits — thus the lost profits doctrine. Infringing on future profits is presented as a theft deserving of compensation.

The problem here is that all property and wealth are legal creations of the state in the first place. Foreign investors' property only exists because the state defends it with the threat of violence. Corporate lawyers would have you believe that property is part of the fundamental structure of the universe, like the Ideal Gas Law and Planck's Constant, but in reality there is no such thing as a pre-political property right.

This can be illustrated with the case of Germany, as economist J.W. Mason has done. That nation has far less wealth than might be expected — even less than economic basketcases like Spain. The reason is, under Germany's legal regime, the rights granted to owners of things like stocks or houses are far less extensive than they are in places like Spain (or the U.S.). As a result, they are far less valuable as property.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Therefore, it is logically incoherent to portray any duly passed government policy as necessarily a theft that requires compensation. When it comes to determining who owns what, and how much things are worth, government and laws are an inescapable foundation of the entire system.

That wouldn't make outright nationalization of foreign assets or any other policy a good idea necessarily, or foreclose joining up with the TPP. It is just to say that such a scheme amounts to corralling the state into enforcing property rights in certain ways and not in others.

Of course, it is true that ISDS is all but certain to be abused. Australia, Uruguay, and Britain have been sued by tobacco companies under international law for requiring plain packaging on cigarettes — and thus depriving them of a future profit stream. TPP supposedly contains various provisions limiting this sort of behavior, but given the structure of a tribunal, the massive expense of litigating international law, and the huge imbalance in power between the biggest corporations and the smaller Pacific Rim countries, we should be extremely skeptical they will work.

There is also no need for extra-national enforcement of property rights in developed nations, where property rights are already strongly protected. (ISDS provisions were originally justified by the weakness and instability of developing nations' institutions.) TPP will merely give yet another venue for corporations to go jurisdiction-shopping when they want to extort a payout from some nation that got talked into signing away a big chunk of sovereignty.

So why is all this stuff in TPP in the first place? It is likely that President Obama views this through a foreign policy lens. He wants to bind the various Pacific Rim nations into a U.S.-led trade pact before China gets enough hegemonic power to create its own version. There's just one problem: None of these countries particularly want the stuff of a traditional trade agreement — tariffs and other barriers are low, and the economic benefit from TPP is likely to be miniscule at best.

So the administration basically turned the entire process over to the corporate sector. Eight-five percent of the members of U.S. trade advisory committees are from private industry or trade associations. They larded it up with a bunch of corporate handouts, sprinkled in a few giveaways to labor and environment to grease the legislative wheels, and are relying on a massive lobbying effort to get it passed.

It might well work. But let's not fool ourselves. When it comes to dispute settlement, corporations are just looking for ways to abuse the state's monopoly on force for private gain.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

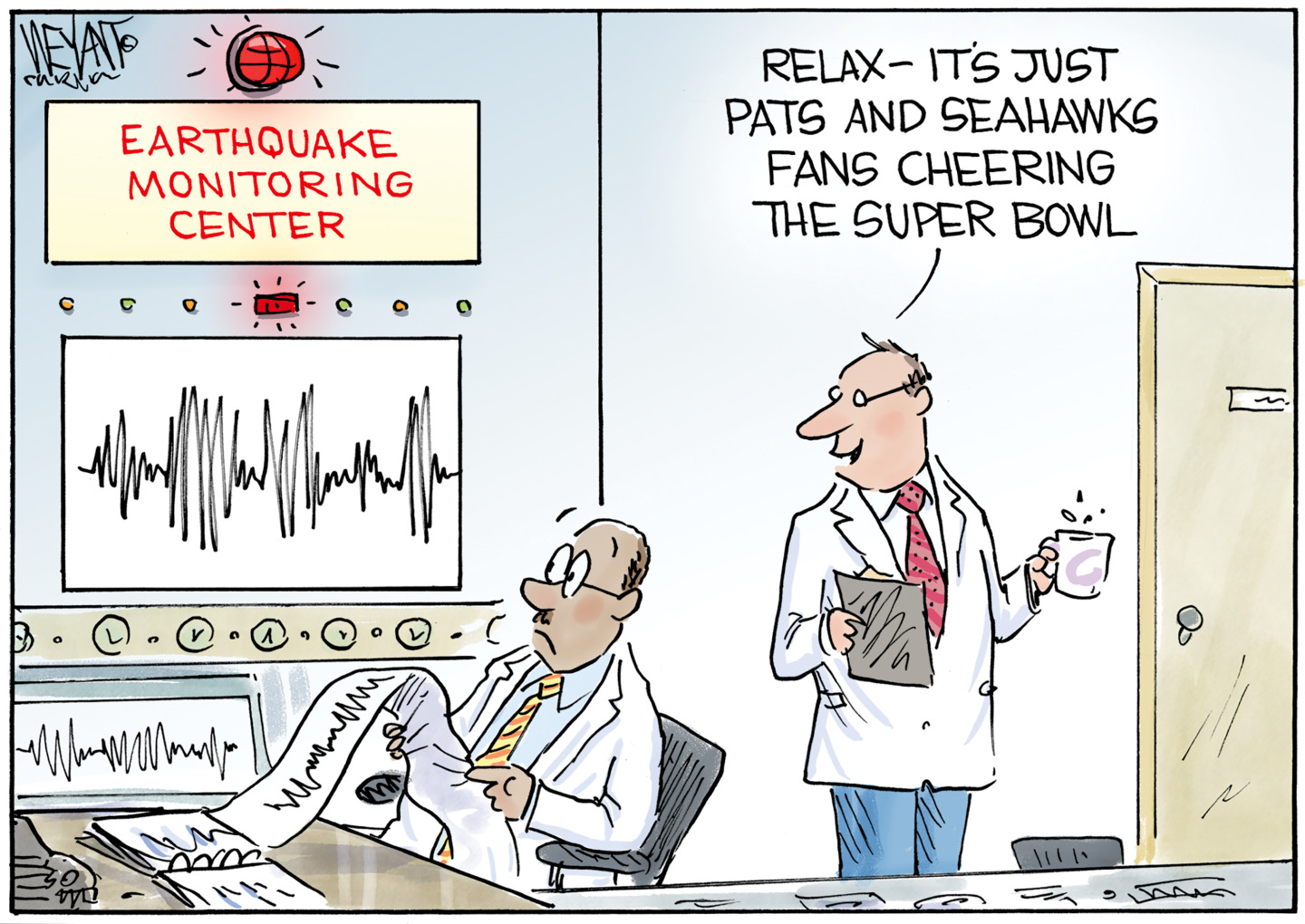

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

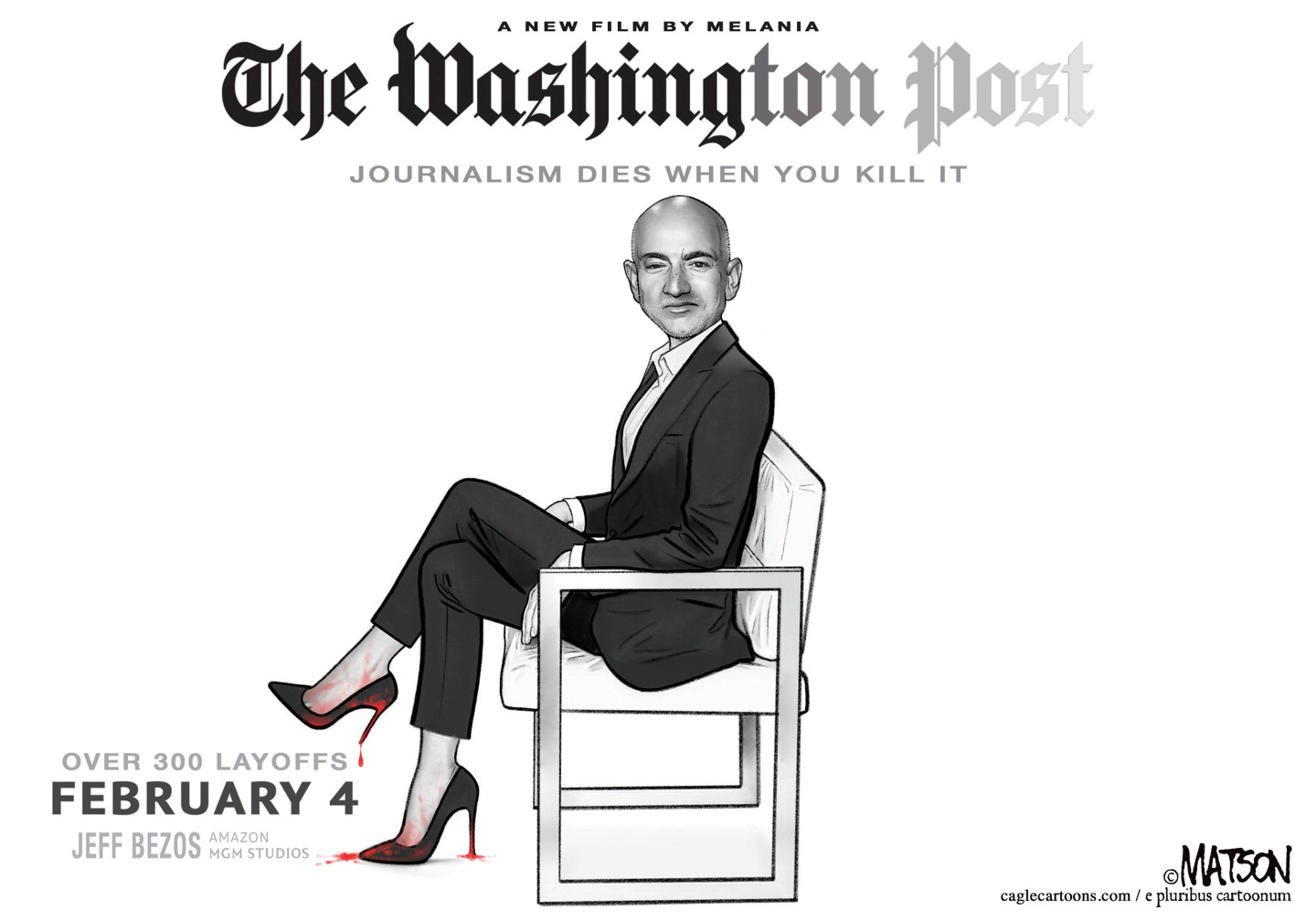

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions