What the Russell Simmons RushCard fiasco reveals about our unequal economy

There's a reason low income people are dependent on services like RushCard

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 2003, hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons founded RushCard, a prepaid debit card company he hoped would help less fortunate Americans. Last week, thanks to a series of technical glitches, that hope blew up in its customers' faces. Most of them have little or no access to traditional banking, making RushCard their primary entry point for financial services, and their economic security often hangs by a thread. So when accounts went down for thousands of RushCard's users last week, their lives were thrown into upheaval.

But, more importantly, even when its computers are functioning, RushCard is a bad deal for the poor. "On top of a monthly fee, RushCard customers pay to withdraw from ATMs, to make point-of-sale transactions, to make signature transactions, and to receive paper statements," Jamelle Bouie explained at Slate. "They also pay if their account is dormant."

The ostensible purpose of financial services — be it traditional banking, or nontraditional forms like pawn shops, payday lenders, and prepaid debit cards — is to provide people liquidity when they need it and to give them a base from which to build their wealth over time. But the nontraditional forms have become purely extractive: They bleed people dry in exchange for the mere opportunity to continue participating in the economy at all. "Without financial tools that are fair, all you can do is basically tread water," Jonathan Mintz, CEO of the Cities for Financial Empowerment Fund, told The New York Times.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Understanding why this is, and how so many Americans got caught in this trap, reveals how the economy has shifted under our feet.

Nontraditional financial services like RushCard have expanded rapidly in recent years, as traditional banks have shuttered many branches and abandoned low-income customers. In 2010, more banks closed than opened across the United States for the first time in 15 years, shuffling off their mortal coil with some assistance from the Great Recession. Things have not improved since, and have arguably gotten worse.

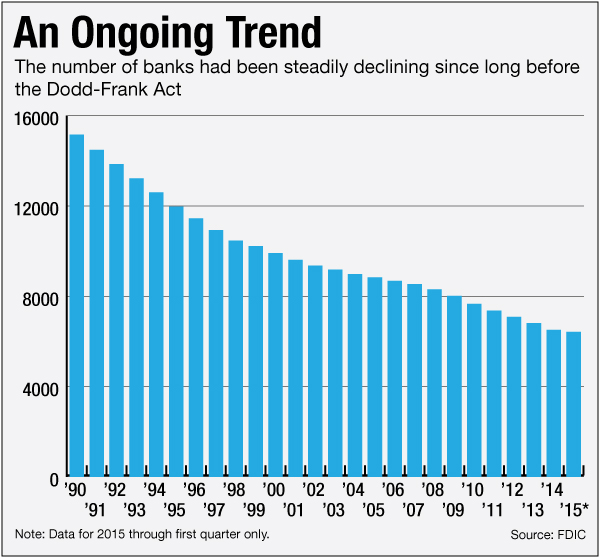

The conservative knee-jerk response is that overbearing regulation is what's killing off traditional banks, but the data doesn't fit that story. The decline has been going on for decades: There were over 18,000 banking institutions in the 1980s, then less than 16,000 by 1990, then just over 6,400 in the first quarter of 2015. The trend line barely twitched after 2010, when the latest round of regulation was passed by Congress:

(Graph courtesy of American Banker.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Consolidation has been a big part of the story. From 1985 to 2013, banks with less than $100 million in assets declined by 85 percent, while banks with more than $10 billion in assets tripled in number. Institutions with less than $10 million were the hardest hit of all, and credit unions have seen their numbers dwindle from around 18,000 in 1980 to just over 6,200 this year.

What's critical to understand is that there's been a distinct geography to this decline.

In areas where yearly household income is at or below $50,000 (and roughly half of all U.S. households make $50,000 or less), nearly 400 banks closed between 2008 and 2010. It was even worse in communities where household income tends to be below $25,000. But in neighborhoods making over $100,000 a year, more branches actually opened over the same period. In poor neighborhoods, "you won't see bank branches," John Taylor, president of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, also told the Times. "You'll see buildings that used to be banks, surrounded by payday lenders and check cashers that cropped up."

As of 2013, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 25.4 million Americans have been going without any bank account at all, and another 67.5 million have an account but still rely heavily on the nontraditional financial services. That's roughly one-fourth of the national population. So the traditional banking industry has been pulling up stakes from poor neighborhoods, and the payday lenders and prepaid debit cards have flooded in to fill the gap. That's because providing financial services for the poor, who lack steady incomes by definition of being poor, is a fundamentally different challenge for banks from providing those services for everyone else. As Bouie notes:

When one month is flush and the other is fallow, it's hard to maintain a balance, which leads to fees and other hits to your income. The FDIC found that more than 57 percent of unbanked households said they didn't have enough money to keep an account or meet a minimum balance, while 35.6 percent of underbanked households said the same. Likewise, almost one in three unbanked households reported "high or unpredictable fees" as one reason they did not have bank accounts. [Slate]

In short, it's about maintaining a viable business model. Payday lenders and prepaid debit cards have to be extractive for the same reason traditional banks leave low-income Americans behind entirely. When you're dealing with the income flows that characterize most poor communities, exploitative banking models are the only banking models that can turn a sufficient profit. The paradox is built into the very economic fabric of the situation.

So the shifts in where traditional banks and the payday lenders and prepaid debit cards can all be found is a microcosm for the entire American economy. Wages have stagnated, inequality has shot up, and jobs have become ever more scarce in recent decades. Meanwhile, sectors that serve and hire primarily amongst the upper class are the ones that have actually recovered since the Great Recession, and that remain economically vibrant. So the traditional banks have found they simply can't function in more and more neighborhoods, and have pulled up stakes to go where the action is. And because traditional banking affords the opportunity to build wealth, while the nontraditional services prevent it, a negative feedback loop sets in that drives the poorer neighborhoods even further into the ground.

Which lends a certain poignancy to Simmons' original hope that RushCard could give people a boost into middle-class dignity. This is, at best, a problem that the private for-profit market cannot solve. At worst, it exacerbates the decay.

Which is why reporters like Bouie and David Dayen, along with the USPS inspector general and Bernie Sanders, have all stumped for the idea of using the postal service to provide traditional banking services to the poor. It would effectively create a "public option" for banking services, unencumbered by the paradoxical demands of the profit motive. And President Obama may well be able to do it with the legal power he already wields.

We absolutely should do this. But more deeply, Americans need to realize that what got us into this mess in the first place was our failure to create enough jobs, and our failure to distribute the immense bounty of our economy in anything like a just or equitable fashion.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.