Democrats and Republicans love government wage subsidies. But they might have it all backwards.

A conversation with venture capitalist Nick Hanauer

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On the question of what to do about low wages, there are two schools of thought in American politics.

Conservatives generally oppose the minimum wage, but favor government spending to top off incomes. Expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) — a refundable tax break for low-income workers — is the preferred route. Liberals generally favor expanding the EITC and hiking the minimum wage, often arguing the two complement one another.

So you have potential bipartisan agreement on the EITC, and bitter divides over the minimum wage. Even Warren Buffet, a billionaire investor often admired by liberals and progressives, has thrown down for the EITC and against the minimum wage.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But Nick Hanauer, the venture capitalist and pugnacious critic of rising inequality, begs to differ. "I'm not saying we should eliminate the EITC," Hanauer explained. But the EITC is at best an ameliorative surrender to inequality, and at worst risks perpetuating the spread of parasitic business models. "I am saying the preponderance of responsibility for living wages should and needs to fall on the shoulders of the companies that employ those workers."

Every business is a "hub" in the economy through which money flows. Revenues come in, then expenses go out. Some of those expenses are operating costs, some are new investments in capital, some are profits paid out to shareholders, and some are wages paid to workers. Over the last three decades, those hubs have gone through a profound shift: less flowing to workers and investment, and more flowing to profits and shareholders.

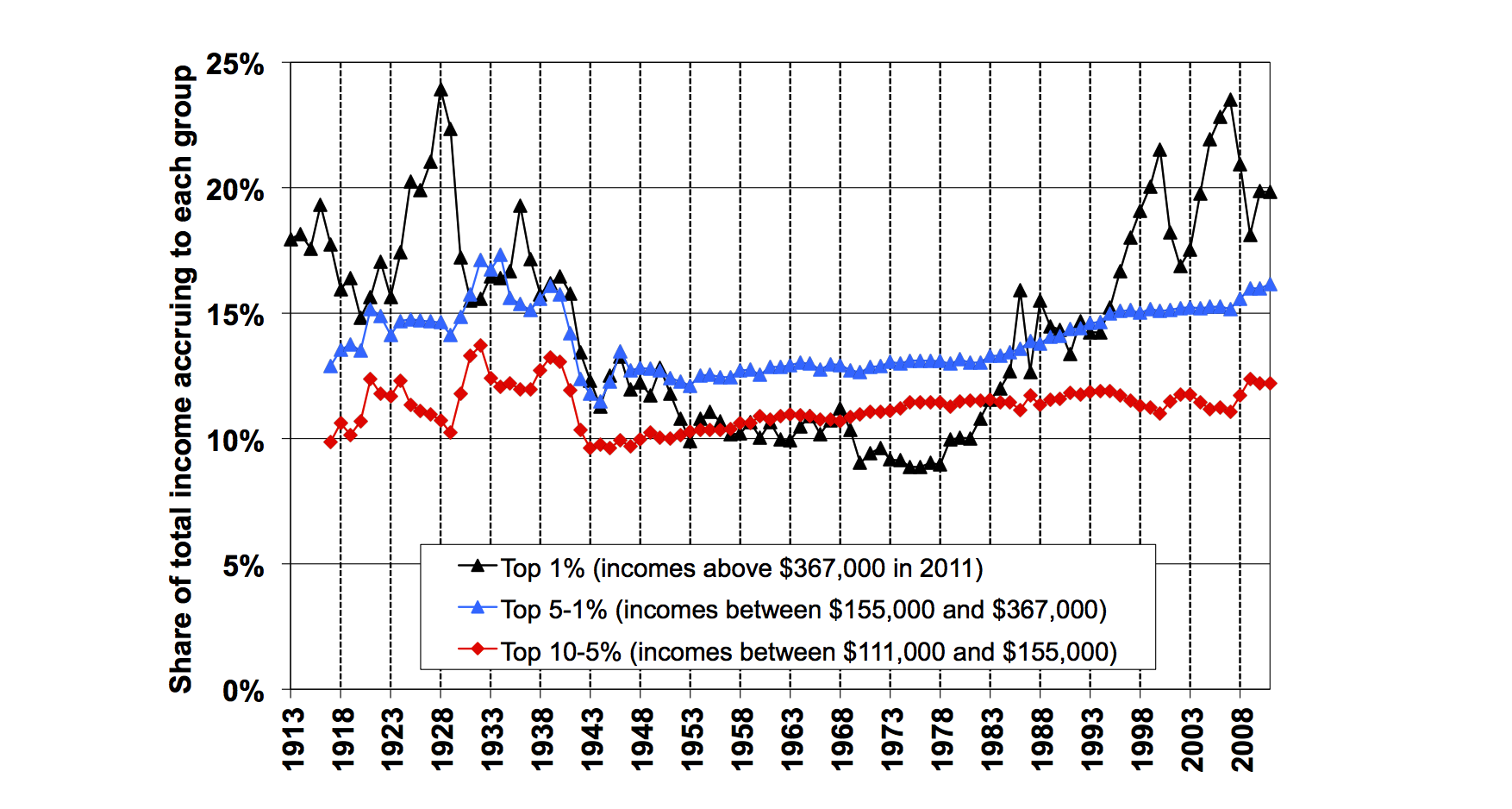

That's changed the aggregate flow of money through the entire economy. After-tax corporate profits doubled to 10 percent of the economy, while worker pay fell from roughly 50 percent to 43 percent. The money couldn't go both places at once. Most of it went to the tippy top, where earners get their income from a mix of wages and the capital gains financed by corporate profits. But the distribution of money within the remaining wage flow shifted too: more to the top and less to the bottom. All told, something in the area of 15 percent of the economy shifted from everyday workers to the top 10 percent since the 1970s:

(Graph courtesy of Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States (Updated with 2011 estimates) by Emmanuel Saez, Jan. 23, 2013. Income is defined as market income including capital gains.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Over $16 trillion now flows through the economy annually. Fifteen percent of that is $2.4 trillion. If it hadn't shifted up, we'd be talking over $8,300 more for every man, woman, and child in the bottom 90 percent, every year, year after year.

"This is all a consequence of the changing way in which we deal with the relative power of workers and earners," Hanauer said.

This brings us to the minimum wage. As a policy tool, it attacks this problem at its source, forcing every business — every "hub" — in the economy to shift its flow of money back down to workers. And it does this from the bottom up, by raising the floor for the very poorest in the bottom 90 percent. But we've failed to update the minimum wage or index it to inflation, so its real value fell from 1970 to 1990, then flatlined.

Meanwhile, the EITC allows these flows to continue on their current course, while using government spending to make up the difference for workers. By Hanauer's calculations, increasing the EITC sufficiently to deal with the money flow problem would require hundreds of billions of dollars annually, and you'd need to get that money by taxing the richest Americans first. (If you just cut government aid in other areas, you'd simply take from the poor with one hand while helping them with the other.)

Neither of those options seem politically realistic. And even if they were, you'd simply achieve the same downward redistribution of money that the minimum wage achieves. Except you'd do it through a complex, jury-rigged route via the U.S. government, rather than the comparatively simple route of just forcing business models across the nation to retool themselves.

Only if you accept the new unequal money flows as good — or at least inevitable — does the case against the minimum wage, and for the EITC, emerge. If we just have to make do with less money flowing to workers, keeping everyone employed requires breaking that flow up into smaller chunks (i.e. lower wages per job), which is what the EITC facilitates.

So it's essentially a government subsidy for a particular kind of business model — one characterized by low wages and high profit margins. Obviously, that's a great deal for business and capital owners. But as Hanauer points out, "economies, like all other human endeavors, are collective action problems." The more businesses get the EITC deal, the more they'll want it. "Capitalists have this fantasy that 'we will run our businesses and pay our workers poverty wages,' but 'you will all run your businesses and pay your workers great wages.'"

The logical endpoint is a self-reinforcing spiral towards low-wage business models, while the cost of paying decent wages is, ironically enough, ever more socialized. "If it's valid to call anything a distortion of the market," Hanauer continued, "then the EITC absolutely distorts the market every bit as much as the minimum wage." It's simply a question of what your "distortions" favor.

Conversely, a higher minimum wage drives businesses to a model of high wages and low profit margins. That creates more consumers who can buy the small businesses services — everything from haircuts to piano lessons — that drive employment. "Our economy is a service economy," and you can't really outsource services. Companies that have based their business models on paying low wages "will either need to change or they will go bankrupt," Hanauer continued. "But the beautiful thing about capitalism is someone will find a way to do the same thing as well or better while paying living wages."

That's why it's hard to find disemployment effects from minimum wage hikes. The real value of the federal minimum wage rocketed up from 1950 to 1970, with no discernable effect on national employment. In Hanauer's own Washington State, the minimum wage for tipped workers went up 85 percent from 1988 to 1990 — and restaurant growth outpaced that of the state as a whole over the next 10 years. Their customers were more prosperous, which made the high-wage business models workable.

Those businesses that do adapt will join the downward flow effect, setting up a virtuous cycle of increasing bottom-up purchasing power and thus more job creation. This is the final irony of Hanauer's argument: It actually relies on the experimental, adaptive power of free markets.

"Capitalism works super well when companies pay workers a living wage," he concluded. "It's quite simple and efficient."

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.