Does paying workers more hurt business? A complete guide to the minimum wage.

Businesses like to say that minimum wage hikes force layoffs and push costs onto the consumer. Is that true?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The minimum wage is on a roll. The latest victory came last week in New York City, where officials proposed hiking the minimum wage to $15 an hour for the city's fast food workers.

It's just one of many remarkable accomplishments for worker groups across the country, and it seems to be tapping into the zeitgeist. Two-thirds of Americans support a federal minimum wage hike, and the vast majority of Democrats support raising it to $10 or more. President Obama wants a national hike to $10.10 an hour. Hillary Clinton hasn't picked a dollar figure yet, but she's throwing her weight behind the New York City push.

Republicans and conservatives remain opposed to the policy, saying it makes jobs scarcer for low-wage workers who aren't employed. The New York Times' David Brooks just summed up some research, offering an unsure-to-skeptical take.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So what should you, dear reader, make of all this?

Before we get into the studies (and there are lots and lots of studies) it might help to lay out the theoretical groundwork. Hiking the minimum wage raises "the cost of labor" for businesses. Once this happens, companies can react in three different ways:

- They can keep all their workers, and pay the higher cost by taking it out of other parts of their revenue stream. The most obvious way is to cut into profits, but they might find efficiencies elsewhere in their businesses.

- They can keep all their workers, and pay the new costs by raising prices — though obviously this risks losing business.

- They can keep their labor costs the same by laying off workers. (New and growing businesses might add jobs more slowly in the context of a higher minimum wage, based on these same calculations.)

So the increased pay is balanced against the possibility of fewer jobs. How this hashes out company to company depends on both the nature of the business model (how much of the revenue is going where?) and the nature of the local market (can it absorb a price hike without business for the company decreasing?). Hence the concerns of critics: Since a low-paying job is better than no job, why make it any harder for businesses to hire?

But we're not nearly done gaming this out. The first option — keep your workers and just pay them all more — is actually the easiest way out for a company if it can do it. No one likes firing people, and restructuring business models is difficult and annoying.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

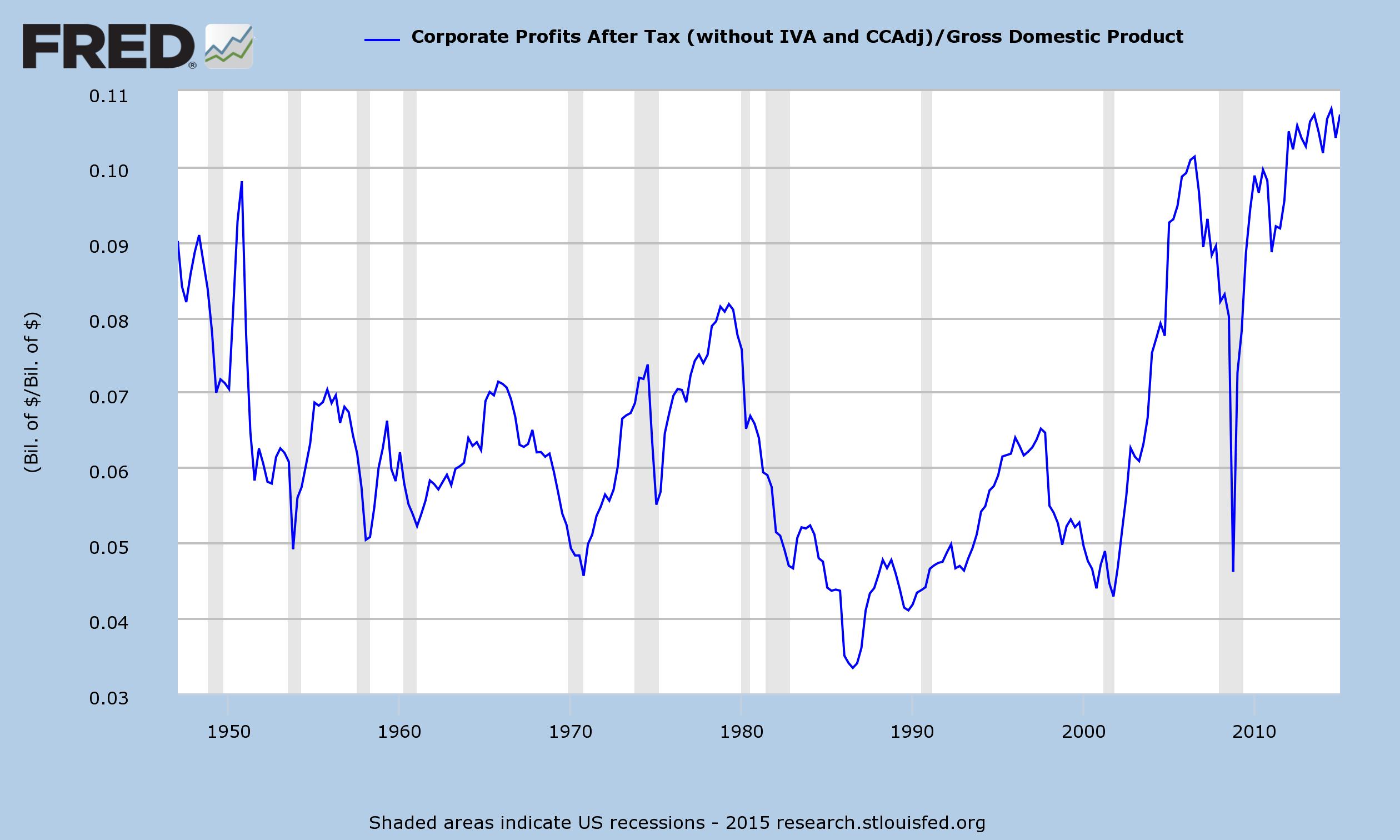

This is where the data starts entering the picture. Corporate profits are now almost 11 percent of the economy, which is higher than they've been in over 60 years.

The portion of corporate revenues going to workers has dropped from a high of almost 84 percent, in the economic boom of the late 1990s, to 74 percent now — the lowest in over 30 years. Finally, two-thirds of low-wage workers are employed by large businesses of over 100 people that typically make a profit.

In short, at the aggregate national level, it looks like there's an enormous amount of room in the typical business model to pay workers more without causing any disemployment effects. This is one of the less-appreciated qualities of the minimum wage: While there may be a price for labor, it isn't fixed. It's negotiated between how badly workers want the job, how badly employers want to hire them, how little pay workers will accept, and how much pay employers will tolerate. The minimum gives workers a bargaining advantage in that give and take.

In that sense, if the minimum wage isn't high enough to at least threaten most companies with job loss, it also isn't forcing them to share all the revenue with workers that they could.

This gets to a second complication. The minimum wage essentially shifts the flow of money within business models: from richer people (management and shareholders) to poorer people (low- and mid-wage workers). Poorer people are more likely to spend additional income than save it, which means money going to them has a bigger "multiplier" — the impact on related economic growth elsewhere in the economy.

So the minimum wage can boost aggregate demand in areas where it boosts pay. That in turn increases the potential revenue local businesses can take in, which offsets the pressure on companies to cuts costs by firing or not hiring. The minimum wage also forces up the pay for workers earning somewhat more than the minimum, in a bottom-up effect.

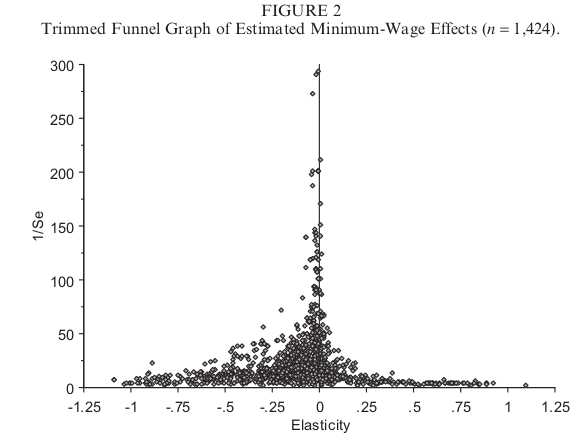

Put all this together, and you have a mass of competing forces set off by the minimum wage — some pushing employment up, and some down. That’s why a 2009 meta-study — a study of 64 other studies — found a convergence on zero employment effects. (The x-axis below is the effect on employment, the y-axis is the statistical precision of the study.) In other words, the pros and cons cancel each other out.

(Chart courtesy of Publication Selection Bias in Minimum-Wage Research? A Meta-Regression Analysis, 2009)

Three final thoughts.

First is geography: Different areas with different costs of living and levels of economic activity will react differently to the same minimum. A wage of $15 may be aggressive nationally, but somewhere like Los Angeles or New York City, it's a lot more reasonable. One proposed rule of thumb is that you don't risk disemployment until you get above half of a given area's median wage. It actually wouldn't be hard to create a national minimum wage framework, indexed to inflation, that adjusts in response to local economic realities.

But it should also be remembered that the minimum wage could serve as a tool, in concert with other policies, to drive areas towards a higher standard of living.

That brings us to the second thought, which is context: The minimum wage and its consequences don't operate in a vacuum. Lots of other tools — from monetary policy, to public investment, to safety net spending — can drive us towards full employment and boost aggregate demand as well. If minimum wage hikes push down the employment-to-population ratio, those other policies can push it back up. We could also retool our safety net, moving away from programs that substitute for higher wages, and onto universal programs that people get regardless of their wage level.

The question is not merely, is the minimum wage good or bad on its own? It's what role does the minimum wage play in your broader idea of a just economy and society?

Finally, it's worth noting that, adjusted for inflation, the current federal minimum wage ($7.25 an hour) is actually lower than it was in the late 1960s ($9.54 an hour). From 1950 to about 1970, growth in the real value of the minimum wage tracked growth in productivity. Then the two diverged. If they hadn't, the minimum wage would be $18.42 today. (For some ridiculous reason lawmakers never got around to indexing the minimum wage to inflation.)

This at least suggests there's a possible variation on the American economy in which a much higher minimum wage is perfectly compatible with full employment and broadly shared prosperity.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy