You know who likes lackluster economic growth? The rich.

Why the 1 percent have reason to cheer a disappointing jobs report

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The job creation numbers for September were a bucket of cold water in the face. Six years after the economy began recovering from the Great Recession, and we're still nowhere close to getting the job market back to full health.

Whatever tribal divisions may cut through American society, we can all at least agree that's bad, right?

Not so fast. A dark and unpleasant truth is that many economic elites actually have a vested interest in anemic job growth and a slack labor market.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

To many observers, this probably sounds crazy. Tight labor markets — when the demand for workers has caught up with the supply — are part and parcel of a booming economy. And a bigger pie benefits everyone!

But this leaves out the crucial issue of worker bargaining power. When labor markets are as tight as they can get — a.k.a. full employment — workers can quit jobs they don't like and find ones they do like with ease, while owners of business and capital become ever more desperate for adequate labor. This gives workers much more leverage to demand wage increases, so they claim a bigger share of all the income generated in the economy. Which means, by definition, the elite's share must shrink.

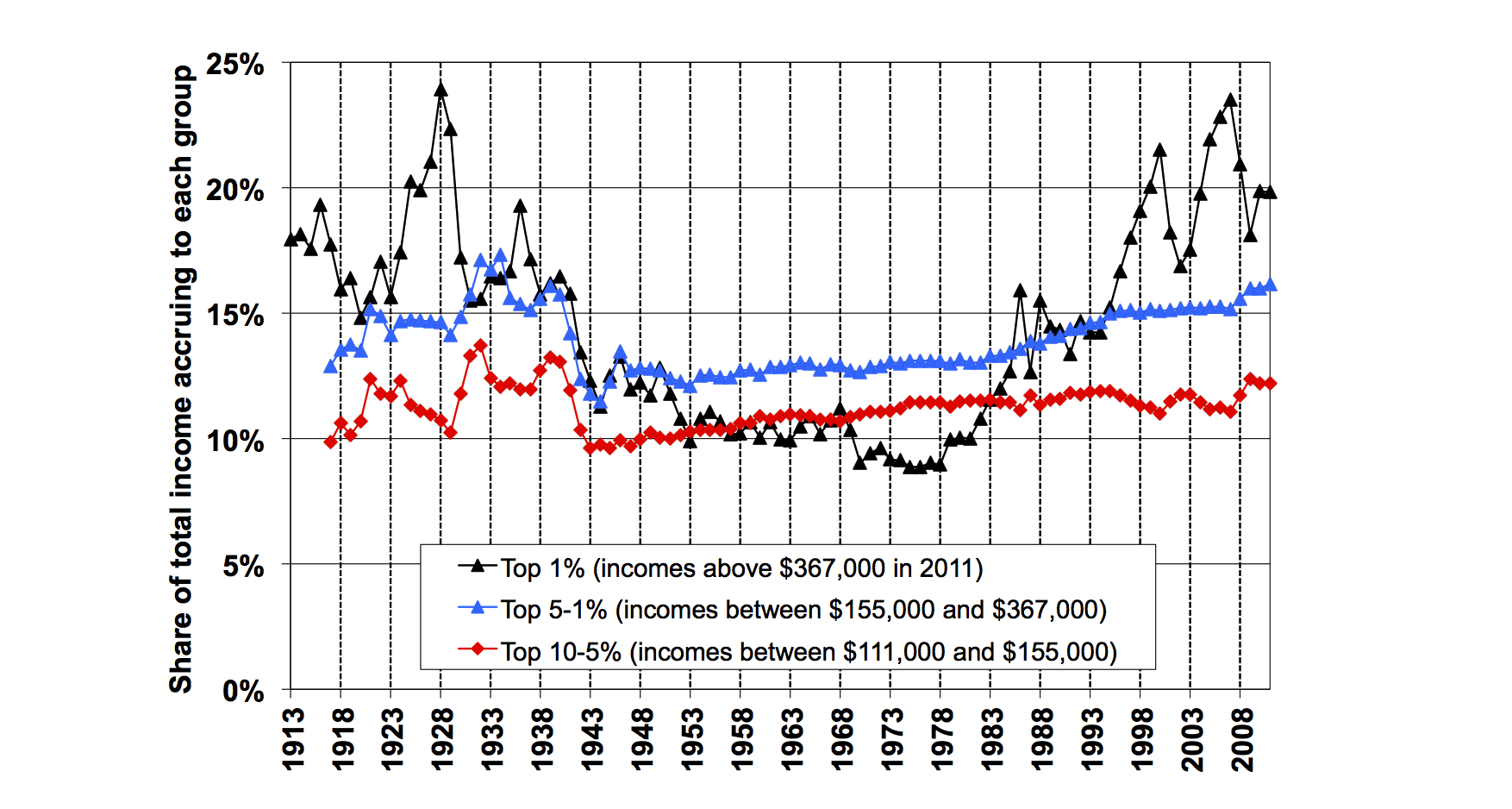

We hit full employment pretty regularly from 1950 to 1970, and just look at what happened to the top 1 percent's slice of the pie during that time:

(Graph courtesy of Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States (Updated with 2011 estimates) by Emmanuel Saez, Jan. 23, 2013. Income is defined as market income including capital gains.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Conversely, after 1970, full employment disappeared, and inequality took off. The one exception was the boom in the late 1990s — for that brief period, the incomes of the top 5 percent of households, the bottom 20 percent of households, and everyone in between, rose in lockstep.

But why should the elite care? So what if they're getting a smaller slice of the pie, as long as the pie is growing for everyone?

Because of how this downward distribution of income plays out in practice. The main channel is the flow of money through individual companies. Higher wages mean the costs of labor go up, so profit margins shrink and businesses have to operate on much tighter finances. Conversely, after full employment went away, corporate profits boomed. Companies obviously prefer the second scenario. It also means the CEOs, management, shareholders, and investors who own stakes in companies get much bigger payouts from those capital gains.

Full employment also takes power over the business away from owners and management and gives more of it to workers instead. Unions grow and labor movements ferment. Workers suddenly can demand all sorts of stuff, from paid leave to ergonomic work stations to different schedules to better treatment and conditions and on and on. The people at the top lose a fair amount of creative control over the nature and direction of the enterprises they view as theirs. Pride is a thing with human beings, and there's a reason unions are so hated in certain quarters of our society.

Finally, there's a lifestyle issue at play. If the incomes of everyday workers go up, then elites' real incomes must go down. The labor they're buying is more costly. This completely changes where and how the elite can spend their money, and what they can and can't consume. The rising "servant economy" rests on a wide relative gap between high and low incomes. Again, we're talking about sinful, fallen, prideful humans here, who like being able to buy bigger, hipper, posher stuff than everyone else, and who like being able to go to high-end cultural events and work creative jobs and eat nice food while other people do the shopping and cleaning and cooking and driving and child care. Full employment and its impact on inequality has a profound effect on the fabric of our shared lives as they're actually experienced.

Now, there's a fair number of data signals for gauging the tightness of the labor market. Wage growth is still flatlined at around 2 percent annually, when it should be at least 3.5 percent. Labor force participation is way down, and underemployment is still quite high.

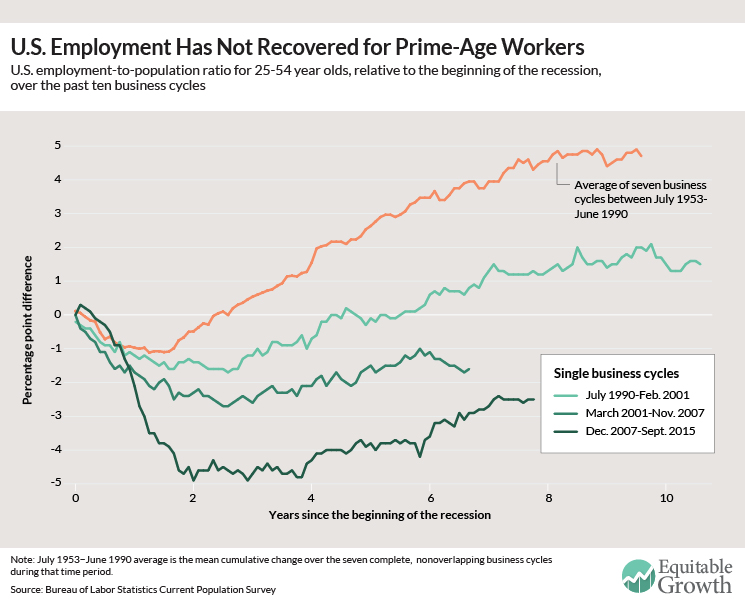

But maybe the best metric is the percentage of the prime-age work force — too old to be students and too young to retire — that's employed. That number still hasn't recovered to where it was before 2008, and that peak was still below where it was before the 2001 recession. The late 1990s boom, while better, was also less impressive that what went on mid-century.

(Graph courtesy of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.)

That downward drift you're seeing there is the primary tool by which the American elite gobbles up ever more wealth and power from everyone else. Recessions in the last few decades have been the inflection points for ratcheting up that effect.

Individual workers and employers don't create jobs. The supply of work is a collective accomplishment, driven by the feedback loop between consumers and businesses. It's a question of ecological stewardship and managing aggregate demand, and it implicates macroeconomic policies from monetary policy to taxes to the welfare state to unions.

Now, maybe it's just a giant cosmic coincidence that elite policy preferences on all those matters are exactly what you need to slow the supply of jobs to a trickle. Maybe it's all unintentionally coordinated by those matters of self-interest, ideology, pride, and human nature mentioned above. But slow the supply of jobs it does, keeping workers desperate and forever on the ropes.

Elites obviously don't want to completely tank the economy. But it certainly works for them if it stays modestly stagnant, maximizing the growth of the pie while minimizing worker bargaining power.

It's the Goldilocks principle: Don't run the economy too hot or too cold. Run it just right.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day