Why John Kasich's moral concern for the poor isn't enough

The governor of Ohio makes a big show of caring for the poor. So why are all his anti-poverty policies so weak?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Tuesday, Ohio Gov. John Kasich joined the race for the presidency.

He is not your average Republican: He accepted ObamaCare's Medicaid expansion in Ohio, earning him the undying fury of many conservative commentators. He's pushed against the most punitive conservative responses to immigration, and he's willing to puncture the bootstraps mythos that economic success is a matter of personal character.

On the flipside, Kasich hasn't been above attempts at union-busting, or shifting Ohio's tax burden off of businesses and the wealthy and onto the middle class and the poor. But in a poignant piece that gets at the governor's messy humanity, Elizabeth Bruenig argued Kasich's Christianity has driven him to a genuinely striking moral stance (for a Republican) towards the poor and the safety net.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That's put real daylight between Kasich and the rest of the GOP: "He's got to come up with an answer that is better than, 'I like poor people, I want to help poor people,'" Stephen Moore, of the arch-right-wing Heritage Foundation, told Bloomberg.

"That's not an answer that conservatives are very persuaded by."

The tragedy of John Kasich is that this moral bravery alone will not be enough. And the insufficiency is not about winning some kind of lefty-approval-for-Republicans contest. The insufficiency is a matter of concrete results: Admirable moral stances are, by themselves, of little use if uncoupled from economic know-how.

By all accounts, Kasich's attempts to cut income and business taxes in Ohio, while raising regressive sales taxes and other taxes on consumption, don't emerge from some random aristocratic urge to punish the poor. He has a very specific model in his head for how economic growth works, and which policies boost it. Crudely put, it's the "supply-side" theory of economic policy that has dominated right-wing thinking for some time: Businesses create new jobs when the costs of bringing on a new employee are outweighed by the benefits of tapping as-yet-unmet demand. And what stands in businesses' way are income and corporate taxes that suck the profit out of such moves.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Kasich has said he'd be down for similar income and corporate tax cuts on the national stage, and he wants to focus on increasing business investment — "the single biggest thing," in his judgment, "that would help us to overcome wage stagnation." To that same end, he wants to balance the federal budget to increase investor confidence, as well as alter expensing and depreciation rules — which he believes will make workers more productive and thus push up wages.

But America's corporate income tax, capital gains taxes, and the income tax are all at historic lows. And that nadir in tax rates has happened while business investment and research and development budgets in the economy have also been on a downslope.

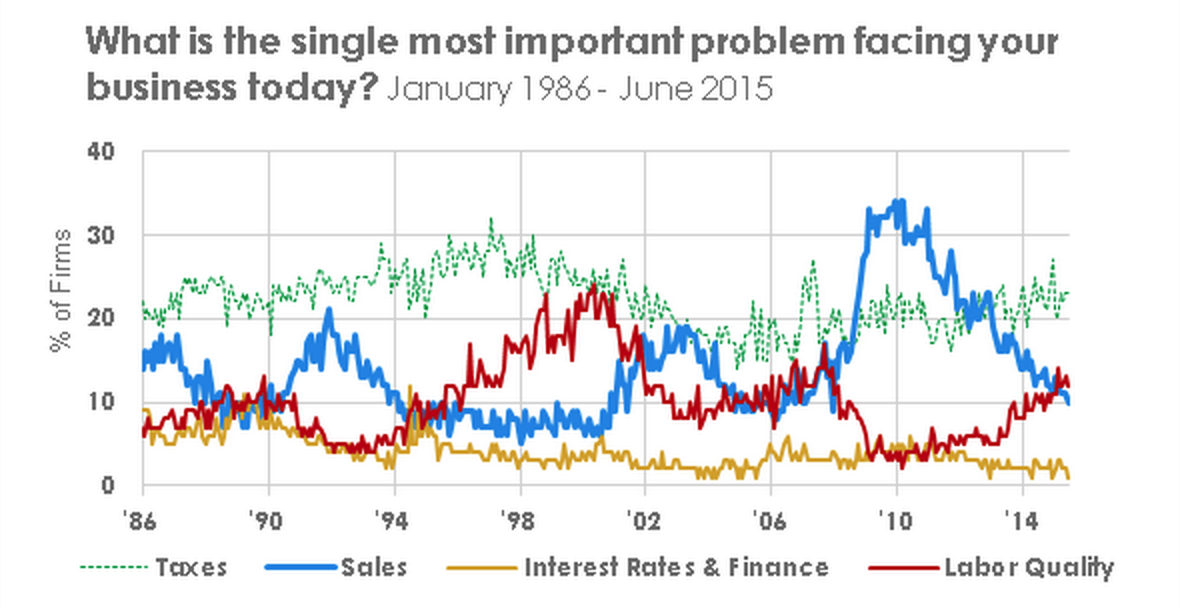

Then there's the word of mouth from businesses themselves. The National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB) has been running surveys of small businesses for decades, and concerns with taxes as an impediment to business function are not at all high compared to the historical trend.

(Graph courtesy of the National Federation of Independent Businesses)

Also note the number of businesses saying sales are their biggest problem. The general critique from the left of the supply-side approach is that it assumes there's already enough demand out there to create plenty of jobs from. (Hence, "supply-side" not "demand-side.") Small businesses' concerns with sales are back to their historic norm, but only just, and after a massive upward spike with the Great Recession.

Finally, look at concerns with labor quality. They're ticking up — and news stories are proliferating about how employers can't find people with proper skills. But look at when concerns with labor quality peaked: the late 1990s, during the country's last genuine economic boom and burst of full employment. It would seem employers complain loudest about the quality of their employees when they can't pick and choose from the labor force — when jobs are so plentiful that any worker might leave at a moment's notice for a better deal.

This should be a reminder that the circumstances that make employers happiest are not necessarily the circumstances conducive to maximizing employment and broadly shared prosperity. The amount of demand and sales that satisfies business owners is one thing; the amount that delivers enough jobs for all Americans is quite another.

(And since Kasich is concerned with investment, also note that business owners' concerns over interest rates — the cost of borrowing and investment — are as low as they've ever been.)

It is not just possible, but probable, that the problem with the economy is not government burdens on businesses at all, but that there's simply not enough demand out there for businesses to tap into for job creation. If that's the case, then cutting or altering taxes won't help, nor will balancing budgets to instill confidence, since neither addresses the actual problem. Kansas relied on a similarly mistaken diagnosis when it cut its business taxes, and the result was a lot more money going into the pockets of upper class Kansans, but no new hires.

Other evidence that demand is the problem: Corporate profits as a share of the economy are up, while workers' wages as a share of the economy — and as a share of corporate revenue — are down. Seven years after the 2008 collapse, wage growth is still flat and there are still more people looking for work than there are jobs to be had. Employers aren't even looking that hard for employees: the time, effort, and money they devote to recruitment is still down from its pre-2008 level, and even further below its late-90s level.

This is not a picture of an economy where demand is plentiful, but businesses just can't tap into it. This is an economy in which demand is just not there, and the burden of taxation is simply not a relevant issue.

If Kasich wants to help the poor, and get us back on the road to full employment, he needs a strategy to fix that — one that actually responds to economic reality.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred