The folly of the Fed's expected rate decision, in 1 graph

The economy isn't just suffering from the Great Recession. This is a far deeper rot.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 12 days, officials at the Federal Reserve will conclude their final meeting of 2015 to decide what to do about interest rates.

A hike in the rate is increasingly looking like a fait accompli, and Fed Chair Janet Yellen did nothing to slow down that speculation with a speech on Wednesday. The November jobs report, released Friday, was in many ways a slight downshift from October, but given what we know of the Fed's thinking, it also gave little reason for them to change course.

I've made no secret of my own belief that a hike of any sort would be grossly premature, and a growing chorus of commentators, economists, and activists have been sounding the same note. But in fairness to Yellen and her colleagues, this dilemma is part of a much deeper pickle the Fed has lately found itself in — one that points to what is arguably the central mystery, not just of the current American economy, but of the global economy as a whole.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And one way to explain it is with something Yellen brought up on Wednesday: The real natural rate of interest.

As Paul Krugman explains, the "natural rate is a standard economic concept dating back a century; it’s the rate of interest at which the economy is neither depressed and deflating nor overheated and inflating. And it’s therefore the rate monetary policy is supposed to achieve."

If unemployment is too high, you theoretically want to push interest rates below the real natural rate to boost job creation. On the other hand, if inflation is rising and you want to tap the breaks, you'd push them higher.

Now, interest rates throughout the economy are set by a whole host of sometimes competing forces in the market. But the Fed can profoundly influence them through pushing the federal funds rate, it's primary weapon, above or below what it believes to be the real natural rate.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There's only one problem: The federal funds rate can't really go below zero. There have been some instances of negative interest rates showing up in the real world, but it's far from clear how sustainable they are or whether they can go negative more than a point or two. This issue is known as the "zero lower bound," and the federal funds rate has been stuck there since the Great Recession.

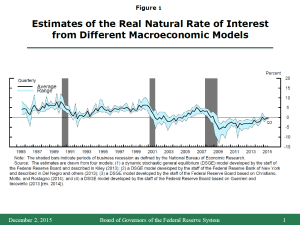

So with all that in mind, here's the chart Yellen presented of how we think the real natural rate of interest has behaved over the last few decades, drawn from various models.

(Graph courtesy of Janet Yellen and the Federal Reserve Board of Governors.)

I assume you can see the problem.

The real natural rate of interest has steadily trended downward since at least the late 1980s. With each successive recession, it gets closer to breaching the zero lower bound, where the federal funds rate cannot follow. It touched zero in the 1991 recession, briefly dipped below it for a year or two with the 2001 recession, and then tunneled deep below it with the Great Recession. And only just now — seven years later — has it returned to zero.

Now, the way interest rates are believed to effect economic growth is through investment: Lower rates make it cheaper for individuals and businesses to make the kind of real economic investments that increase the supply of jobs and wages. If the Fed can cajole interest rates a bit below the real natural rate of interest, then the process should occur faster. On the flip side, if the Fed pushes interest rates above the real natural rate, then its putting drag on that same process.

But the federal funds rate flatlines at zero whenever the Fed tries to chase the real natural rate of interest below the zero lower bound. The Fed isn't just prevented from helping the economy — it's effectively forced to hold it back from recovering. This, according to Josh Bivens, research director of the Economic Policy Institute, is why fiscal policy is the best option for boosting the economy out of recessions: It's direct spending, and faces no zero lower bound problem. And that's why "things have been so crummy" ever since the federal government decided to embrace austerity and cut the deficit and spending, he told The Week. "The economy really needed a negative federal funds rate. And we can't get a negative federal funds rate."

This gets to the first reason a hike in the federal funds rate would be premature. As Yellen herself noted in the speech, there are lots of reasons to think the current unemployment rate of 5 percent is deceptively low, and the labor market is doing worse than that number implies. So while the real natural rate of interest just returned to zero, we still want the federal funds rate to go below it.

Finally, we come to that aforementioned economic mystery: Namely, why has the real natural rate of interest been slowly falling all these years? If you've heard of the "secular stagnation" debate between economists like Larry Summers, Paul Krugman and Ben Bernanke, that's basically what they're arguing over. "Something in the economy is making it harder and harder to generate demand growth that's strong enough to keep the economy on trend," Bivens explained. "You see this reflected in the falling neutral rate of interest. The Fed has to be more and more permissive over time, just to keep demand growth steady at trend."

There's no consensus over why this is happening (Bivens pointed to inequality as one major culprit) but whatever the cause, one thing Yellen's graph makes clear is that the real natural rate of interest can repair itself over time. It dived after each recession, but then began rising again. It's just that each recession has hit before the rate could return to its previous peak. So the hole just keeps getting deeper.

Which is the second reason the Fed should hold off. At this point, we're not just talking about giving the economy time to recover from the Great Recession. We're talking about giving it time to recover from a far deeper rot that's been going on for decades.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.