The best books we read in 2015

The Week's writers and editors reflect on the books we loved reading the most this year

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, by Susanna Clarke

"Epic fantasy with footnotes" might not be a description that screams "page-turner." But Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell — Susanna Clarke's 2005 tome chronicling the rivalry between two magicians — rises above its density to deliver an addictive and intoxicating brew of drawing-room wit, Gothic passion, and fairy-tale whimsy. Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell simultaneously demonstrates that fantasy doesn't have to be juvenile and "literary" doesn't have to mean "dull." Its incisive commentary on class and madness is matched by its giddy originality and the vastness of its imagination. Above all, Clarke's prose is enchanting, luring readers into a world of romance and horror, fog and fairies, stuffy mansions and wild moors. It casts a spell you wish would never break. –Amy Woolsey, contributing writer

Middlemarch, by George Eliot

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Scholars often call Middlemarch one of the best novels ever written. Frankly, I was steeling myself for a bit of a slog. After all, this is an eight-volume novel about English provincial life in the 1830s. But its immersive, detailed narrative quickly began to feel like a rare luxury. Long as it was, I was a little sad when I finished Middlemarch. After six weeks of steady reading, the last thing I wanted to do was to say goodbye to that world. –Alan Zilberman, contributing writer

The Peripheral, by William Gibson

After a 15-year absence from science fiction, William Gibson returned to what he calls his "native literary culture" with astounding results. The Peripheral tells the story of not one but two futures described in alternating chapters, each as richly detailed as the cyberpunk world that made Gibson famous in Neuromancer.

The first shows an eerily believable near-future rural America in which working for a 3D printing outfit or making drugs are the only real employment options outside of the military of Homeland Security. The second future, a century ahead of ours, takes place after an extinction event called "The Jackpot" — the all-too-logical extrapolation of a tomorrow as rendered by climate change. Man has made his bed, but only the poor must lie in it, because the rich can insulate themselves. It's a sci-fi narrative with an emotional heart that appeals to anyone living in our increasingly dire world. -Chris Lites, contributing writer

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Signature of All Things, by Elizabeth Gilbert

You'd be forgiven for harboring doubts about Gilbert after encountering the well-written but rather threadbare self-actualization of her bestselling memoir, Eat Pray Love. I certainly did. But then I read this gorgeous, sneakily modern homage to the capacious novels of the 19th century. As botanist Alma Whittaker, "born with the century" in 1800, sees herself — and the world — change across the decades, Gilbert constructs what you might call a patient page-turner. After meeting our heroine at the moment of her entrance into the world, the tale turns to her father, Henry, for some 40 pages, not one of which seems superfluous.

Built from wry humor, scintillating detail, and the florid mind of one of the most fully realized protagonists in recent literature, The Signature of All Things is anything but threadbare. It's lush and teeming with life. –Matt Brennan, contributing writer

Fates and Furies, by Lauren Groff

Fates and Furies tells the story of a 24-year marriage in two parts: first, from the vantage point of the husband, Lotto, who represents the "fates"; second, from his wife, Mathilde, the "furies." Beneath Mathilde's wifely duties and seemingly doting love on her play-writing husband, she holds within her a powerful anger, steely determination, and an array of secrets unbeknownst to Lotto.

The stark difference in how two halves of the same couple perceives the marriage and each other will leave you contemplating how much truth exists in relationships, and whether honesty is really key to love. –Becca Stanek, staff writer

The Nightingale, by Kristin Hannah

If you've finally recovered from last year's heart-wrenching World War II novel, let me introduce you to this year's literary sock in the gut. Kristin Hannah's The Nightingale follows sisters Vianne and Isabelle during the Nazi occupation of France. Vianne and Isabelle have an estranged relationship stemming from their mother's death, their father's grief-stricken abandonment, and their subsequent divergent paths. Vianne, the eldest, builds a loving family of her own, while Isabelle, an outsider wherever she goes, revels in teenage rebellion. The war shatters both of their worlds, forcing Vianne to fend for her daughter and self, and Isabelle to open her heart to others and risk losing them in the process. The horrors of the war bring out a ferocious bravery in these women, who act selflessly in such inspiring and heartbreaking ways.

Hannah, a "bona fide World War II buff," was inspired by the true-life heroism of the women of the French resistance and based several characters on real people and events. In turn, you'll be haunted by these women, wanting to applaud them and weep for them. You'll be hard pressed to let them go. –Lauren Hansen, executive editor of multimedia

Fear of Flying, by Erica Jong

First published in 1973, Fear of Flying is known as much for being a second-wave feminist masterpiece as for being a deliciously racy, titillating work of fiction. It's the famous originator of the idea of the "zipless f--k": a no-strings-attached sexual encounter of sublime, breathless magnitude.

Isadora Wing is the novel's magnetic heroine, a young woman with a ferocious sexual imagination who finds herself falling into an affair with an eccentric English psychologist while accompanying her husband on a business trip in Vienna. For all her wit and cleverness, Isadora can't figure out one crucial problem: How does a woman take control of her own happiness in a world dominated and defined by men? How does a girl who wants to be a writer, not a wife, find value in herself? How can you love men if you need men?

These are not irrelevant questions in 2015. Despite being born 20 years after Fear of Flying first came out, it's incredible how many of Isadora's problems I recognize as my own. The fact that this book happens to be witty, readable and endlessly entertaining belies its brilliance and depth. –Sally Gao, editorial intern

The Family: A Journey into the Heart of the Twentieth Century, by David Laskin

This is the story of the author's mother's family, spanning several decades and continents to focus on three separate branches — one that stays in Eastern Europe, one that immigrates to the United States, and one that grows roots in Palestine.

Laskin pieces together this complex and intriguing history by reading old letters and interviewing relatives around the world. As the story unfolds, we learn that in America, Laskin's great uncles found success after they started their own business, but it was his great aunt, Ida Rosenthal, who — as co-founder of Maidenform — put brassieres on the map and changed the way women looked at their undergarments.

There's a family tree in the front pages of the book, which helps the reader keep track of how everyone is related, but it also betrays the fate of Laskin's relatives who stayed in Europe. Even though you know what's going to happen, you can't shake the feeling of wanting to change the course of history as you read letters from a cousin wondering why her rich and successful family in the United States can't rescue her family from the horrors they're witnessing in Vilna. But there's also joy as children are born, and long-lost relatives reconnect. By using the words of his ancestors, Laskin chronicles his family's fascinating history honestly, making sure to touch on both their accomplishments and their failings. It's a gripping read that seems especially important today. –Catherine Garcia, staff writer

The War of the End of the World, by Mark Vargas Llosa

Despite its almost 600 pages, The War of the End of the Worlds is one of Mario Vargas Llosa's more accessible novels. It does not play Faulkner-esque games with perspective and time, nor does it rely on a reader's literary knowledge, nor repeatedly interrupt its narrative in a postmodern, digressive manner. It simply tells, from a variety of perspectives, the story of the War of Canudos.

The War of Canudos took place in the very late 1800s in Brazil, when a diverse community attained a degree of autonomy from the nation. As told by Vargas Llosa, it is a religious allegory and story of second chances, a stand-in for Latin American rebellion and war in general, and an examination of the construction of Utopia. Working with dozens of characters, the story immediately takes on an epic scale, but Vargas Llosa loses none of the intimacy that characterizes his best work. Whether it's a journalist, a reformed brutal killer and rapist, or an outcast, Vargas Llosa interrogates his characters with a psychology worthy of Dostoevsky. The key difference is that Vargas Llosa rejects Dostoevsky's melodrama and keeps thoughts and attitudes internal, thereby allowing his events to accrue significance without losing a realistic grounding. and to retain a level of allegorical heft to accompany the historical fiction. –Forrest Cardamenis, contributing writer

Boy, Snow, Bird, by Helen Oyeyemi

"Nobody ever warned me about mirrors, so for many years I was fond of them, and believed them to be trustworthy." From its opening sentence, Helen Oyeyemi's Boy, Snow, Bird casts a spell. The novel — ostensibly a very loose retelling of Snow White set in 1950s America, and centered on a woman who's all too aware she might be judged as an "evil stepmother" — is nowhere near as cute or overwritten as that oversimplified plot description might suggest. Oyeyemi is a brilliantly accomplished prose stylist, and the novel's triptych structure enables her to take the narrative into all kinds of unexpected corners. And though Boy, Snow, Bird was originally published in 2014, its unflinching interrogation of racial and sexuality identity has only become more timely since it was released. –Scott Meslow, entertainment editor

Night at the Fiestas, Kristin Valdez Quade

The stories in Kirstin Valdez Quade's debut collection, Night at the Fiestas, primarily take place in northern New Mexico — and while I've never been there, I now feel as if I have. Set against such a strange and folkloric landscape are Quade's protagonists, who are more often than not trapped in the awkward halfway point between adulthood and dependency. That is to say, they're all vibrantly, excruciatingly real — to the point that I challenge you to keep a dry eye when harm or disappointment befalls them (as it inevitably does). –Jeva Lange, staff writer

Citizen: An American Lyric, by Claudia Rankine

Claudia Rankine's multimedia work Citizen grapples with the pain of experiencing institutional racism in perhaps the most "accurate" way literature can: in fragments. Through poetry, essay, fiction, and image, Rankine conveys the contradictions that produce the black body in the eyes of those who observe it as well as those who inhabit it. Throughout the book, Rankine returns to Zora Neale Hurston's poignant observation, "I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background." Much of the book is left blank, a white space that is both physical and poetic. Like the citizens for whom it is written, Rankine's black text is only visible against a white background that often takes up more space than the words themselves. But here, reclaimed and reappropriated in Rankine's language, it gives them room to breathe. –Roxie Pell, editorial intern

The Rap Year Book, by Shea Serrano

No work this year excited me more — nor better filled the void left by ESPN's blind shutdown of Grantland — than The Rap Year Book by former Grantland writer Shea Serrano. In it, he chooses a song from every year from 1979 to 2014 as that year's most important rap song, and then presents an argument for it. Written with Serrano's unique, hilarious voice, and dotted with charts, graphics, and counter-arguments from the country's best culture writers, it's required reading for anyone who has ever endangered a relationship by arguing for his/her top 5 MCs. –Travis Andrews, contributing writer

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, by Betty Smith

At its heart, the book is a coming-of-age story of Francie Nolan, a girl born into a poor Irish family in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Through little more than her own intelligence, hard work, and her mother's frugal-to-a-fault financial sensibility, Francie almost single-handedly pulls the family out of destitution. While the story is a classic and lovely in itself, reading it while living in Williamsburg is what made it so memorable. Francie walked along the same streets with the same wide eyes that I did — but in her time, just before World War I, Williamsburg was not the semi-glamorous, hyper-trendy neighborhood it is today. Then, the streets were filled other poor children looking for aluminum to exchange for measly cents. It's incredible to bear witness to the remarkable changes that have transformed in the city over the past century. –Stephanie Talmadge, editorial assistant

The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, by Jeffrey Toobin

Health-care subsidies. Same-sex marriage. Housing discrimination. In just one weekend's work at the Supreme Court, all three of these major national issues were shaped by a written decision from America's highest judicial body.

That's why The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court — Jeffrey Toobin's painstakingly researched tome on the inner workings of the highest court in the land — is the best book I read this year. Published in 2007, The Nine is a fascinating curtain-raiser of our judicial history, beginning with why the building's iconic steps are significant and stretching all the way to explaining how nine lawmakers came to decide who would be president of the United States, with more than enough insider info on justices past and present to satisfy the biggest of law buffs.

Even if you're not inherently interested in Washington's inner workings, The Nine serves as a comprehensive contextual touchstone for what's going on in America today. I read the book after the court's landmark rulings this summer, and Toobin helped me understand how the quotable opinions we read come to be: how lawyers bring and argue cases, how the court decides to take them, how the justices form coalitions, how clerks serve as proxy communicators. Stop bugging your closest law-literate friend with a slew of questions after the next big Supreme Court ruling, and read The Nine instead. –Kimberly Alters, social media editor

The Nearest Thing to Life, by James Wood

Somewhere in his newly published collection of essays, the late, great Christopher Hitchens writes that the esteemed critic Edmund Wilson "came as close as anyone has to making the labor of criticism into art." With apologies to Wilson, my nomination for that distinction would be James Wood, the literary critic, essayist, and novelist who cut his teeth writing brilliant and savage book reviews for The Guardian and The New Republic, and who now writes about fiction for The New Yorker and teaches the practice of literary criticism at Harvard.

The Nearest Thing to Life is a slim volume based on the Mandel Lectures that Wood delivered at Brandeis University in April 2013. Like nearly everything he writes, the lectures are deep, passionate, and accessible. Those familiar with Wood's work will recognize the themes: how fiction works, the way it imitates and transmutes our experience of the world, and the mysterious parallels and disjunctions between literature and religious faith. But Wood pushes into new terrain in this book, reflecting on the theme of literary criticism itself to show how such critical writing, when done well, can become a form of art in its own right. As, I would add, Wood's own work regularly does — very much including The Nearest Thing to Life. –Damon Linker, senior correspondent

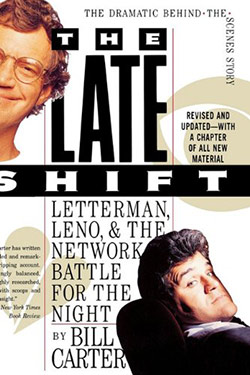

The Late Shift: Letterman, Leno, and the Network Battle for the Night, by Bill Carter

Bill Carter's The Late Shift chronicles the rise of Jay Leno and David Letterman, whose tentative friendship and mutual understanding gave way to conflict and competition in the early 1990s.

This book gave me a new lens through which to view Letterman, a host I've always found fascinating, but rarely understood as a phenomenon. I never got to experience Letterman in his gonzo prime, so the hype surrounding his status as a showbiz legend never gelled with me. Carter's book adds context and nuance to the public personas of two men who appeared on television nearly every weeknight for several decades. Through interviews, narrative, and autobiography, Carter's book offers a reminder that late-night television is a business like any other, albeit much higher-profile and more fraught with acrimony than many. It's worth reading as preparation for whenever the late-night cycle, now in a period of stasis and fraternity, rolls back around to turmoil. -Mark Lieberman, contributing writer