What TV looked like before the Super Bowl

It's been 50 years since the NFL and the AFL squared off against each other on TV for the first time — and the medium could hardly have changed more

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In an era of ever-increasing media fragmentation, the Super Bowl is the rare TV event that touches pretty much everyone — a category it shares almost exclusively with awards shows, other sports championships, and Grease Live!. A 2014 Nielsen study reported the average television viewer has access to over 189 channels and recent findings from Deloitte further scramble the calculus for traditional engagement. With more than 110 million people poised to tune into the upcoming Super Bowl 50, the game's long-standing domination serves as an outlier as entertainment platforms continue to expand.

Of course, the so-called "Golden Super Bowl" isn't merely a way to unify a diverse, sophisticated viewing audience. It's an industry onto itself. "Super Bowl Sunday" defines a whole season in American culture, affecting the entire U.S. economy in surprising ways. It's the second largest day of eating, behind Thanksgiving but ahead of Christmas. And the ratings, which are always massive, somehow continue to rise; last year's Big Game overtook the final episode of M*A*S*H as the highest single rated program in television history.

Even the counter-programming is dependent on the Super Bowl itself. Animal Planet's Puppy Bowl is a beautiful and popular delivery system for one of humanity's great, non-football passions: adorable puppies. The Lingerie Bowl — essentially football plus T&A — aired as pay-per-view counter-programming before spinning off into its own league. And MTV's series of "Butt-Bowls" urged Gen-Xers to skip the traditional halftime show in favor of a Beavis & Butthead special.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

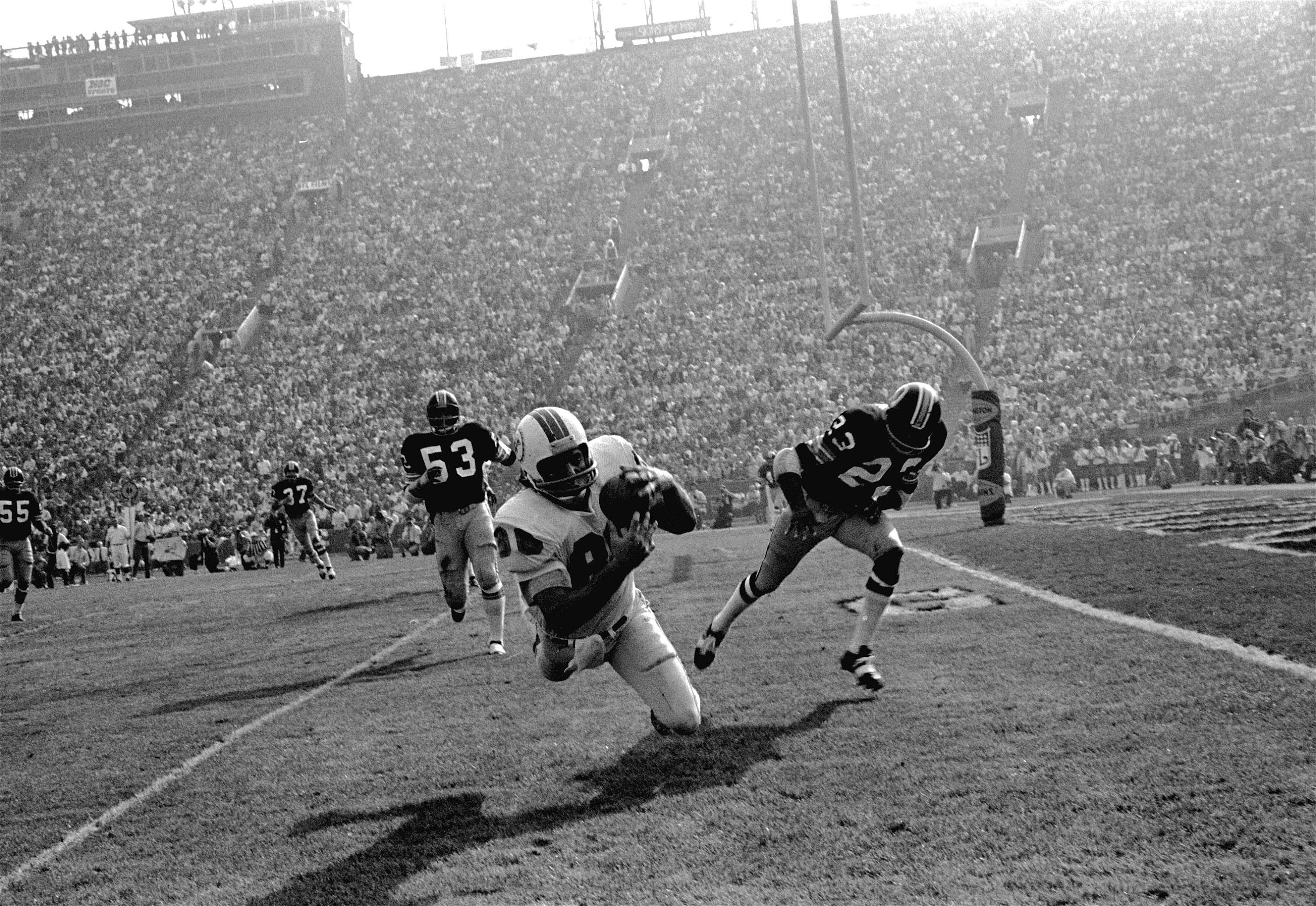

But in all the conversation around this year's Super Bowl 50, one fascinating piece of history was largely overlooked: On Jan. 15, the NFL Network aired the once-presumed lost first Super Bowl. Commemorating the original championship game, which occurred on Jan. 15, 1967, the initial match-up between Vince Lombardi's Packers and the Kansas City Chiefs reveals just how much television has changed over the past half century.

The first thing to know about the original Super Bowl broadcast is that it wasn't known as such until 1969, once the AFL-NFL merger had been finalized. In 1967, it was the AFL–NFL World Championship Game — the culmination of the sport's growing prominence in American life. Particularly following the legendary "Greatest Game Ever Played" in 1958, football had steadily increased in popularity, becoming an increasingly major television broadcast player that was beginning to challenge previous stalwarts like roller derby, boxing, and wrestling. By the early 1960s, CBS had committed roughly $20 million annually for the rights to college and NFL broadcasts. In competition, rival networks NBC and ABC began covering AFL games, invigorating the fledgling league in the process.

At a time before high profile sport events like the World Series were forced into primetime, coverage of each league happened during weekend afternoons, quickly becoming a phenomenon. As a result, the NFL and AFL sought to merge, and plans for a televised championship broadcast — the brainchild of former PR executive-turned-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle — were announced.

Starting a little after 4 p.m. eastern time, "Super Sunday" was simulcast by two networks (to this day, the only time that has ever happened). The reason? CBS still held the rights to televise NFL games, while NBC had the rights to broadcast the AFL. Each network paid $1 million, selling commercials for roughly $40,000 per 30-second spot. Advertisements came from companies selling 10-cent cigars and McDonald's hamburgers. It was, suffice it to say, a far cry from the often-elaborate and high concept commercials shown in later years; current ad buys typically exceed $1 million, with Eminem's two-minute 2011 "Imported From Detroit" Chrysler commercial costing a whopping $12.4 million.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The 1967 game itself was an instant hit, though not the all-consuming cultural lynchpin it would become. The NBC telecast drew slightly more attention (22.6 rating and 26.75 million viewers) than the CBS telecast (18.5 rating and 24.4 million viewers). In total, a combined 51.1 million people caught the game — less than half of last year's historic broadcast of the Patriots-Seahawks game, but still a substantial figure for the period.

However, the competing broadcasts that split up the audience also meant that the game failed to crack the Nielsen Television Index top 10, where it was beat by the Bob Hope Christmas Special and a presentation of Cinderella. Other programs that beat out the splintered ratings for the championship game include The Ed Sullivan Show, where The Rolling Stones performed a censored version of "Let's Spend the Night Together," and an episode of Hogan's Heroes.

Today, nothing comes within a football field's length of the ratings achieved by the NFL. The last eight Super Bowl broadcasts represent the most-watched TV programs, in terms of total viewers, ever — period. Even the pre-game show — a relatively modern invention — is a massive draw, with 2014's five hours of coverage attracting greater viewership than the NBA Finals, the NCAA Tournament title game, and a Triple Crown attempt at the Belmont Stakes. (To be fair, much of today's "pre-game" coverage has almost nothing to do with the game itself — like, say, last year's buzzy interview with President Obama.)

On the other side of the game, you have the Super Bowl "lead-out" — a rare opportunity to entice a massive, engaged audience to watch something new. But that certainly wasn't understood at the time. In 1967, NBC's lead-out program was Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color, which had already been on the air for more than a decade. CBS aired a Lassie episode called "Crisis at Devil's Gorge," in which a young boy is bitten by a rattlesnake.

Today, the lead-out position is highly coveted and hotly analyzed. A well-chosen lead-out — like Friends' aptly titled "The One After the Super Bowl," which drew nearly 53 million viewers after Super Bowl XXX — can introduce a series to millions of potential new fans. This year, CBS is planning on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert as its lead-out, giving the recent David Letterman replacement an eye-catching platform.

But much as things have changed, the roots of the modern Super Bowl can still be found in the very first game. The bombast of the annual Super Bowl halftime spectacle — this year to feature Coldplay, Beyonce, and Bruno Mars — began with a performance by trumpeter Al Hirt, accompanied by a marching band, a high school drill team, pigeons, and thousands of balloons.

But that 1967 halftime show displayed surprising gravitas. As UMass Amherst music professor Willie Hill recently described, two marching bands — the predominantly white University of Arizona and historically black Grambling College — performed alongside one another in a symbolic gesture of racial harmony. Occurring during the peak of the decade's civil unrest, it's a genuine statement from a platform later known for its shock value and off-kilter shark dancing.

And today, it's an apt image for a "big" game that no one realized, 50 years later, would grow so much bigger. The original game is a glimmer of TV's early days — not only in football's development into a cottage industry, but for the medium as a whole.

Andy Hoglund is a contributor to Vice, The Daily Beast and Newsweek, as well as a member of the Boston Online Film Critics Association. He works as a public relations executive at Rasky Baerlein Strategic Communications.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.The Explainer The big game will showcase a variety of savvy — or cynical? — pandemic PR strategies

-

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.The Explainer How to make sense of the Boston massacre

-

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIII

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIIIThe Explainer Most boring Super Bowl ... ever?

-

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio State

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio StateThe Explainer I and millions of other people in these two cold post-industrial states would not miss The Game for anything this side of heaven

-

When sports teams fleece taxpayers

When sports teams fleece taxpayersThe Explainer Do taxpayers benefit from spending billions to subsidize sports stadiums? The data suggests otherwise.

-

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseball

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseballThe Explainer Boston and L.A.? This stinks.

-

This World Series is all about the managers

This World Series is all about the managersThe Explainer Baseball's top minds face off

-

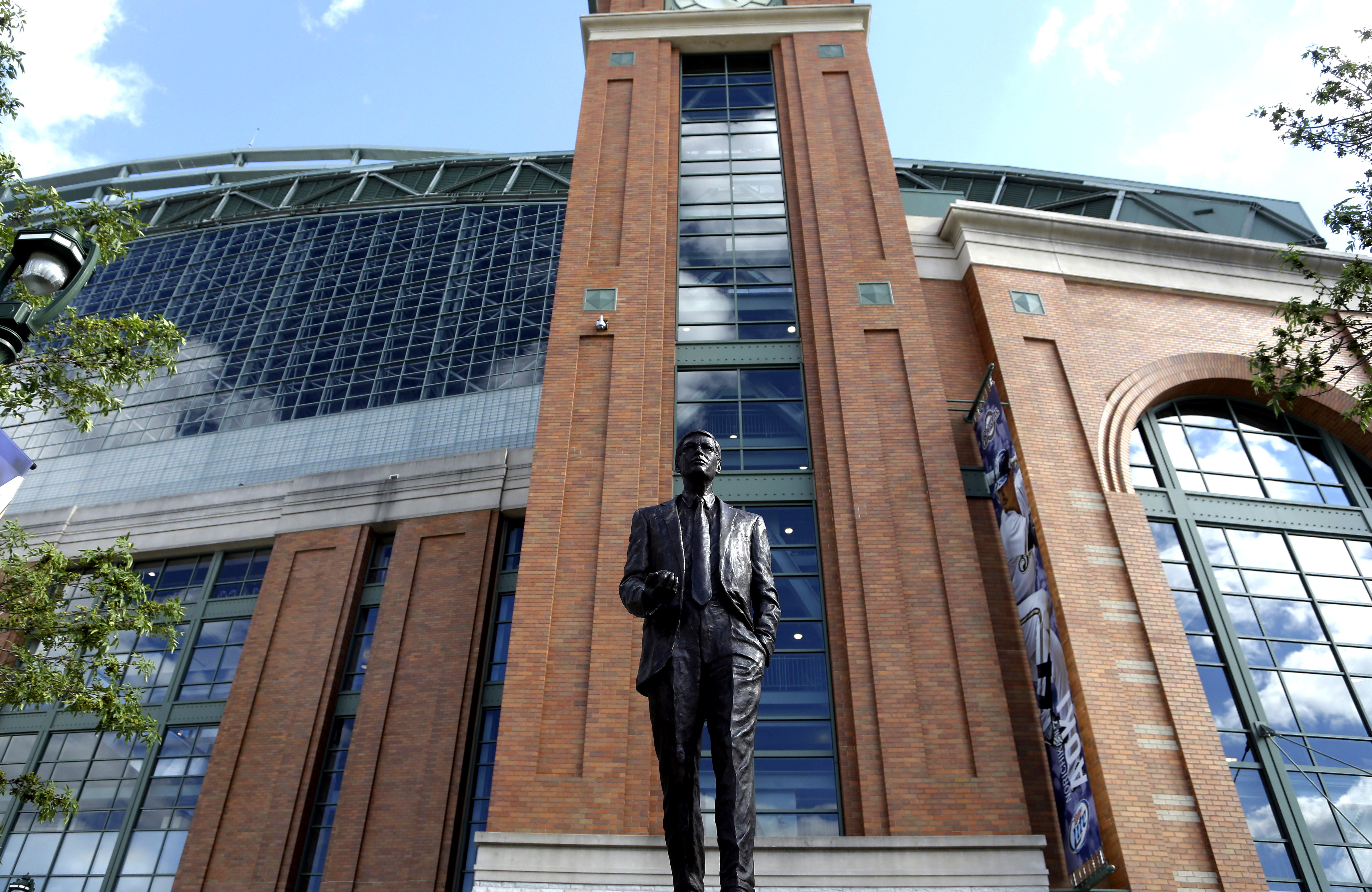

Behold, the Bud Selig experience

Behold, the Bud Selig experienceThe Explainer I visited "The Selig Experience" and all I got was this stupid 3D Bud Selig hologram