When sports teams fleece taxpayers

Do taxpayers benefit from spending billions to subsidize sports stadiums? The data suggests otherwise.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Do taxpayers benefit from spending billions to subsidize sports stadiums? The data suggests otherwise. Here's everything you need to know:

How are stadiums funded?

Public financing of U.S. professional sports stadiums has been common practice since the mid-1980s, with taxpayers shelling out an average of $400 million to build or renovate each of these projects. From 1990 to 2010 alone, 84 new arenas were built at a total cost of $34 billion — of which $20 billion came from taxpayers in the form of federal tax-exempt public bonds and tax credits. Even the wealthiest teams in the largest media markets have received huge public subsidies. When the New York Yankees opened their new $2.5 billion ballpark in 2009, almost $1.7 billion of the funding came from the public. The Dallas Cowboys' AT&T Stadium — the first billion-dollar arena built specifically for football — enjoyed $444 million in public subsidies. And Miami's $650 million Marlins Park — opened in 2012 — will actually end up costing taxpayers more than $2 billion over the life of the bonds Miami-Dade County officials used to prop up a private construction deal. To shake loose these enormous sums from elected city and state officials, privately owned sports franchises often threaten to move elsewhere. "Teams say to cities, in essence, 'Give us $100 million or we'll take away your status as a major-league city,'" says baseball writer and historian Bill James. He calls this practice "a classic, textbook case of abuse of monopoly power."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When did this practice start?

With the exception of several stadiums built as part of Olympic Games bids, the first publicly funded professional stadium was Milwaukee's County Stadium, which in 1953 enticed the Boston Braves to relocate to Wisconsin. But the game changer for publicly funded stadiums was the Baltimore Colts' stunning 1984 move to Indianapolis after Baltimore city officials refused to pay for renovations to Memorial Stadium, the Colts' home field. Sports team owners now had the Colts' example to use in blackmailing cities, and by 1992 taxpayer funds had played a part in subsidizing 77 percent of U.S. professional sports stadiums. "The stark reality is that cities and their leadership are mainly complicit in stadium boondoggles," says urban theorist Richard Florida.

Do communities actually benefit?

Almost exclusively, no. "Studies consistently find no discernible positive relationship between sports facility construction and local economic development, income growth, or job creation," said Brookings Institution senior fellow Ted Gayer, co-author of a detailed analysis of this issue. The promised influx of jobs mostly amounts to temporary construction work and low-paid, part-time positions for stadium vendors and ushers. The biggest myth, say economists, is that stadiums generate new revenue for cities by luring people to spend money in and around ballparks. There's some evidence this is true for minor-league teams in small towns, but research shows that in big cities, "consumers who spend money on sporting events would likely spend the money on other forms of entertainment," said Scott Wolla, a senior specialist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Fans who spend $150 at a ballgame, in other words, are spending money they'd otherwise shell out for movies, restaurants, shows, or concerts. So there's no net increase in dollars spent in the community or sales taxes collected. And in some cases, communities have had to cut other spending in order to finance stadiums.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What kind of spending?

Oakland cut its police force by 18 percent in 2011, in part to help pay the debt from building the Coliseum, thereby increasing average police response time to emergency calls to 17 minutes. In 2014, the struggling city of Detroit cut pensions for retirees by 4.5 percent at the same time it subsidized a new stadium for the Red Wings. Such sacrifices do not guarantee loyalty from teams, which despite their generous public subsidies remain privately held businesses whose billionaire owners usually put their own interests first. St. Louis and San Diego — with Oakland soon to follow — have empty football stadiums that remain saddled with a combined $220 million in public debt. Where are their former teams? In lavish new stadiums that other cities were willing to help finance as a lure for moving.

Have some taxpayers rebelled?

Yes, in a few cities. Voters in St. Louis last year rejected funding a new MLS soccer stadium, and in Seattle, a group called Citizens Against Sports Stadium Subsidies is demanding a referendum on the King County Council's decision to spend $135 million on improvements to the Mariners' stadium, Safeco Field. But public officials remain proactive in offering generous deals to sports teams. Few things are more appealing to politicians than being photographed wearing a hard hat and holding a shovel at the ceremonial groundbreaking of a major stadium for fans' favorite teams. Jeffrey Dorfman, an economist at the University of Georgia, warns fans and other taxpayers against being fooled by such images. "Support your local sports team, but never support public financing of a sports stadium," Dorfman says. "You as a taxpayer are virtually guaranteed to lose that game."

The Braves' real estate empire

At a 2016 meeting with shareholders in the Atlanta Braves' parent company, Liberty Media, CEO John Malone said, "The Braves now are a fairly major real estate business, as opposed to just a baseball club." That's putting it mildly. The Braves replaced their barely two-decades-old home stadium, Turner Field, in 2017 with SunTrust Park — a $722 million stadium in the Cobb County suburbs built with nearly $400 million in public funds. So great was the public's investment in the corporately owned baseball stadium that the county commissioners were forced to raise taxes to fund a depleted $40 million bond delegated for building and maintaining public parks. The Braves also had their spring-training facility and three minor-league stadiums funded by tens of millions of dollars in subsidies from small cities throughout the Deep South. According to Bloomberg Businessweek, the Braves extracted about a half-billion dollars in public subsidies for their stadiums. "If there's one thing the Braves know how to do," said Drexel University economist Joel Maxcy, "it's how to get money out of taxpayers."

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.The Explainer The big game will showcase a variety of savvy — or cynical? — pandemic PR strategies

-

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.The Explainer How to make sense of the Boston massacre

-

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIII

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIIIThe Explainer Most boring Super Bowl ... ever?

-

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio State

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio StateThe Explainer I and millions of other people in these two cold post-industrial states would not miss The Game for anything this side of heaven

-

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseball

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseballThe Explainer Boston and L.A.? This stinks.

-

This World Series is all about the managers

This World Series is all about the managersThe Explainer Baseball's top minds face off

-

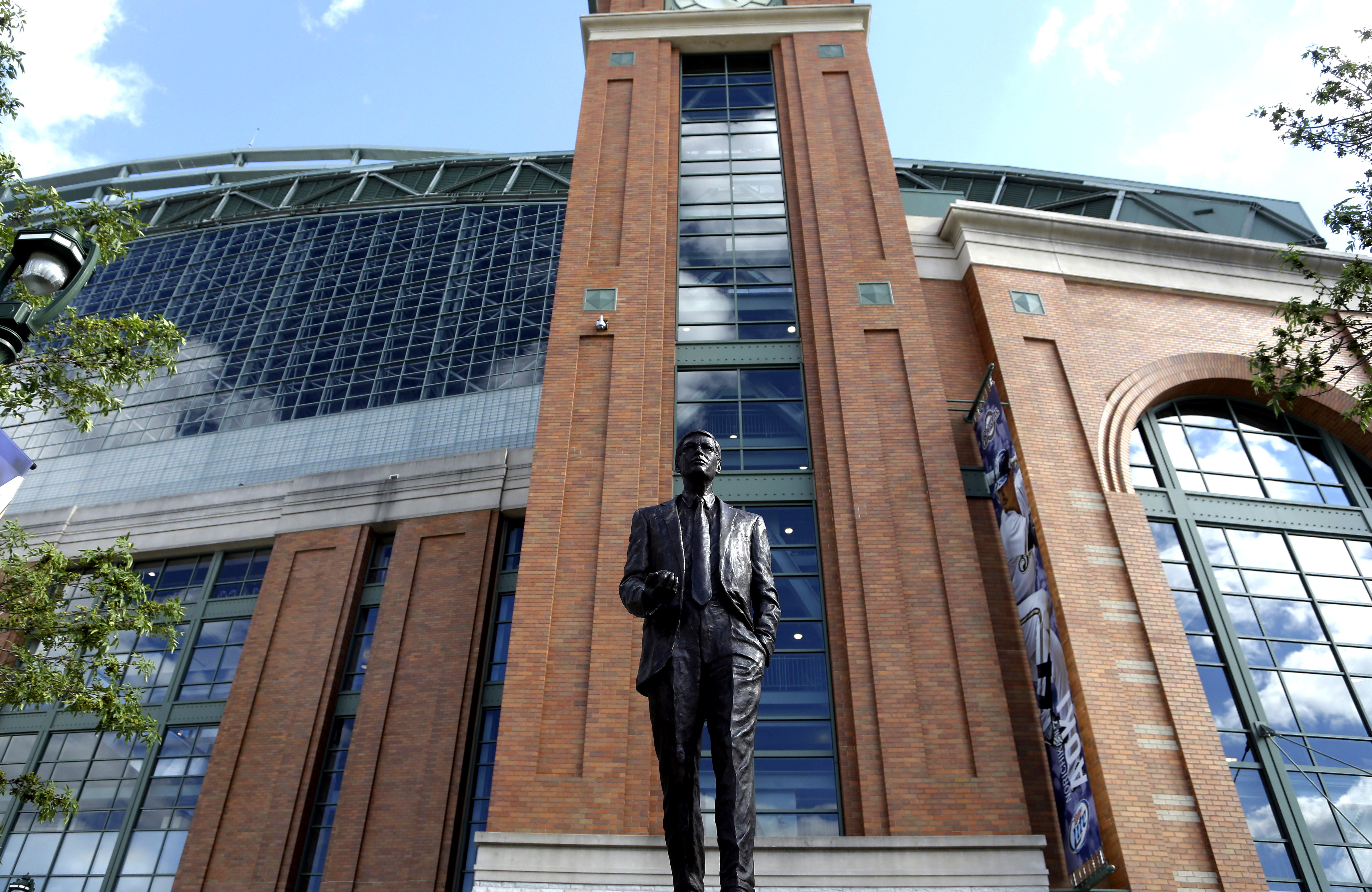

Behold, the Bud Selig experience

Behold, the Bud Selig experienceThe Explainer I visited "The Selig Experience" and all I got was this stupid 3D Bud Selig hologram

-

Who to root for in the MLB playoffs

Who to root for in the MLB playoffsThe Explainer Discover the pleasures of rooting for a team you had no attachments to before just this second