The 2018 World Series is bad for baseball

Boston and L.A.? This stinks.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

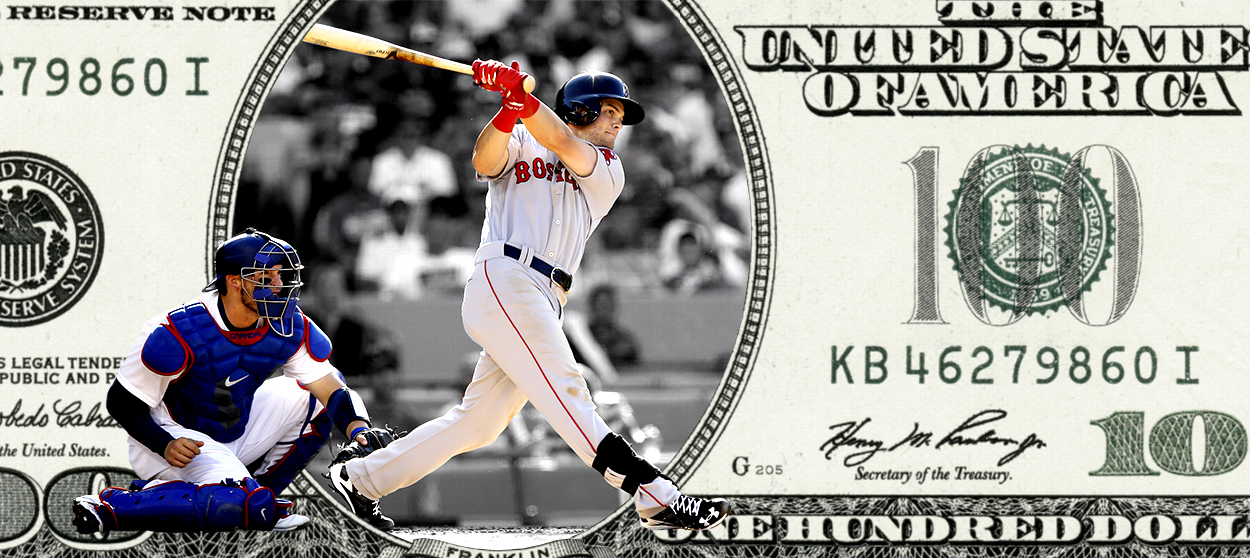

When the World Series is between two of the three highest payrolls in baseball, you know something is broken.

On paper, a Fall Classic between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Boston Red Sox, which begins Tuesday, should be legendary. But it's difficult to muster excitement about the matchup between two of the most storied teams in the sport. That's because, in a year that saw scrappy, innovative teams like the Milwaukee Brewers and the Oakland A's overperform by throwing out long-held conventions, it was the unspectacular power of money that prevailed.

After defeating the Brewers in a decisive Game 7 on Saturday, the Dodgers are returning to the World Series for the second year in a row, capping off six consecutive years in the playoffs. They sit third in Spotrac's real-time ranking of total team payroll, behind only the Red Sox and the San Francisco Giants, at $199 million. The Sox likewise subscribe to the philosophy of throwing heaps of money (more than $228 million, to be precise) at big-name talent. Their reward? A 10th trip to the playoffs since 2003, and their fourth run at a World Series in that same timeframe.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Grumbling about money buying championships is almost as old as baseball itself. While the factors that lead to a winning team are varied — chemistry, management, and luck play no small part — "evidence suggests that the relationship between money and winning is as strong now as it's been any time in the free-agency era," FiveThirtyEight found in 2015. That's not to say poor teams haven't had opportunities. The expansion of the wild card has allowed more underdog teams in the playoffs, and it's now common to see less-moneyed franchises reach the postseason with a little luck and a lot of short-term strategizing. In 2008, for example, the Tampa Bay Rays won the AL pennant despite having the second lowest roster salary in the sport that year.

Still, it's easy to be cynical when the 2018 playoffs featured appearances by four of the seven highest payrolls in baseball (thanks to the Chicago Cubs and the New York Yankees, as well as the World Series contenders).

For awhile, though, it looked like baseball's pluckiest teams might have a real shot at winning it all this year, thanks to their dropping of baseball's longest held conventions. The A's, who had the third lowest payroll in baseball, managed to shake up the end-of-season AL wild card race by emphasizing "bullpenning," i.e. quickly handing the ball to relievers to leverage favorable match-ups. Likewise, the most deserving team to not make the playoffs, the Rays, won 90 games on $25.7 million thanks in part to their use of an "opener," a reliever who starts a game only to be replaced an inning or two later by a more traditional "starter." The result for fans isn't just entertaining baseball — it was a reinvigoration of a more than century-old sport.

The Brewers, who spent the second lowest of all the playoff teams per win ($1.20 million), played the most unfamiliar game of baseball of all. After they swept the mid-market Colorado Rockies in the NLDS by using starting pitchers for a total of just 12 2/3 innings, their experiment seemed to be paying off. In the NLCS against the Dodgers — who started the season with more than twice the Brewers' opening day $90 million payroll — Milwaukee even attempted to trip up L.A.'s lineup by "starting" a southpaw, only to pull him after one batter. Fox's announcer, John Smoltz, admitted repeatedly on air to being baffled by their innovative gameplay. Sadly, such derring-do was unable to overcome the juggernaut from L.A.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The problem is that today's richest teams aren't fools. The Dodgers are known to employ "bullpenning" as much as anyone, only they can still rely on the highest paid pitcher in baseball, Clayton Kershaw, when they need to. The Dodgers have also built an impressive farm system, which has borne fruit both with the development of home-grown stars like Cody Bellinger and Yasiel Puig as well as with the king's ransom of prospects needed to land All-Star shortstop Manny Machado at the trade deadline this year. Machado was an integral part of the Dodgers' NLCS victory over the Brewers and helped secure their division victory, too. As Lindsey Adler said last year, L.A. is "an example of what a brilliant front office would do given near-unlimited resources and a mandate to spend them as shrewdly as possible."

The same could be said for the Red Sox, who've won more than one World Series this century by adopting the strategies of their scrappier opponents, just with better resources. In 2013, the Sox won "(another) Moneyball World Series," using the sabermetrics made famous by the A's in the early-to-mid 2000s. This year, the Sox are looking to again improve on the strategies of smaller-market teams, including an emphasis on the bullpen game. The Sox just happen to be building theirs around perhaps the best closer working today, Craig Kimbrel, who also boasts the fourth biggest contract of any relief pitcher.

The resulting World Series, between two of baseball's biggest-spending titans, is thus a bittersweet marker for the sport. Yes, baseball has never been more exciting — but the small-market teams that made it so are nowhere to be seen. As SB Nation puts it, "when every team is a smart team, money wins out again, just like it did when every team was a dumb team."

The 2018 World Series could have been legendary, a dawning of a new era of the sport. But it turns out money can buy you happiness. At least it can in baseball.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.The Explainer The big game will showcase a variety of savvy — or cynical? — pandemic PR strategies

-

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.The Explainer How to make sense of the Boston massacre

-

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIII

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIIIThe Explainer Most boring Super Bowl ... ever?

-

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio State

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio StateThe Explainer I and millions of other people in these two cold post-industrial states would not miss The Game for anything this side of heaven

-

When sports teams fleece taxpayers

When sports teams fleece taxpayersThe Explainer Do taxpayers benefit from spending billions to subsidize sports stadiums? The data suggests otherwise.

-

This World Series is all about the managers

This World Series is all about the managersThe Explainer Baseball's top minds face off

-

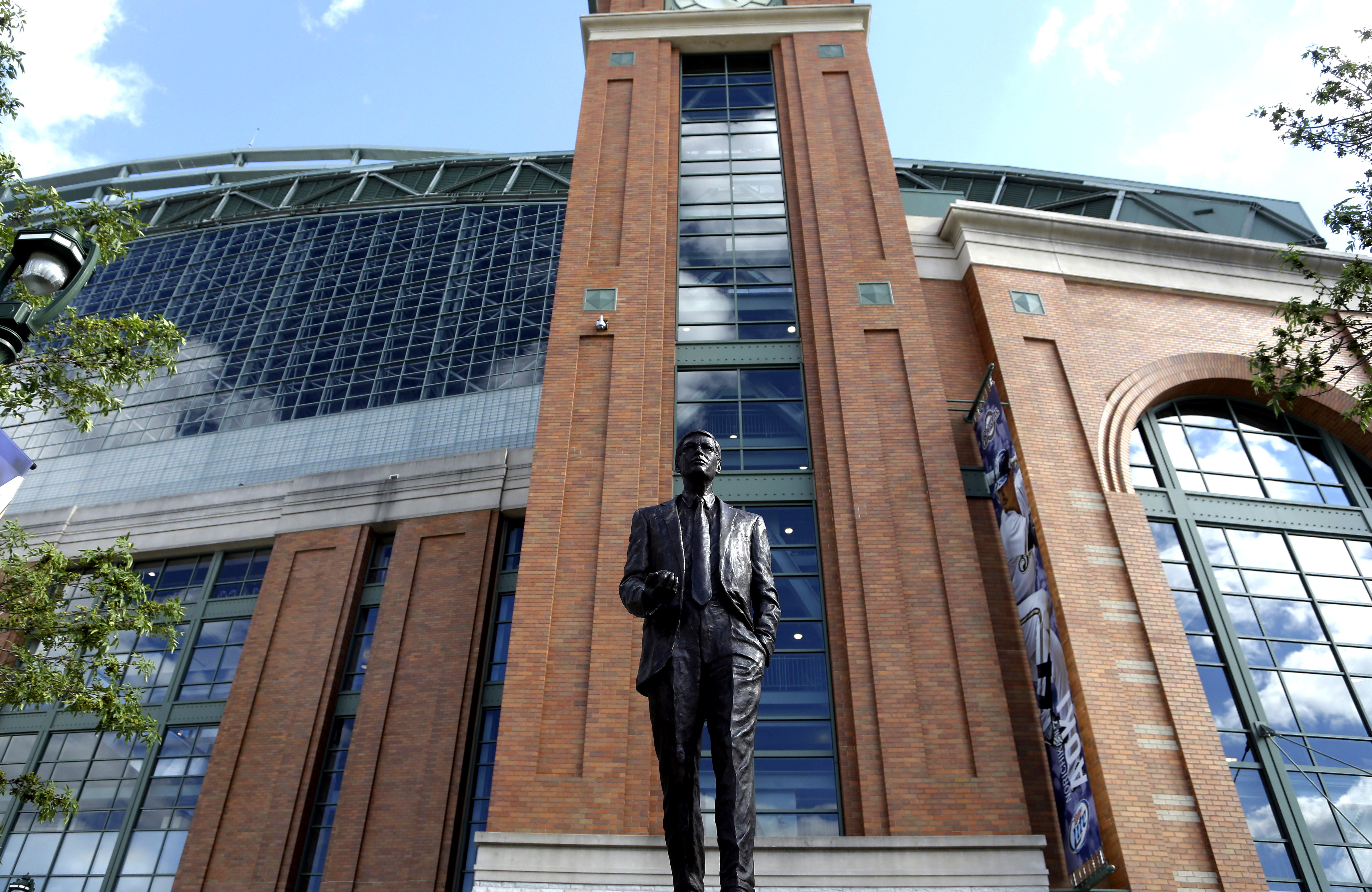

Behold, the Bud Selig experience

Behold, the Bud Selig experienceThe Explainer I visited "The Selig Experience" and all I got was this stupid 3D Bud Selig hologram

-

Who to root for in the MLB playoffs

Who to root for in the MLB playoffsThe Explainer Discover the pleasures of rooting for a team you had no attachments to before just this second