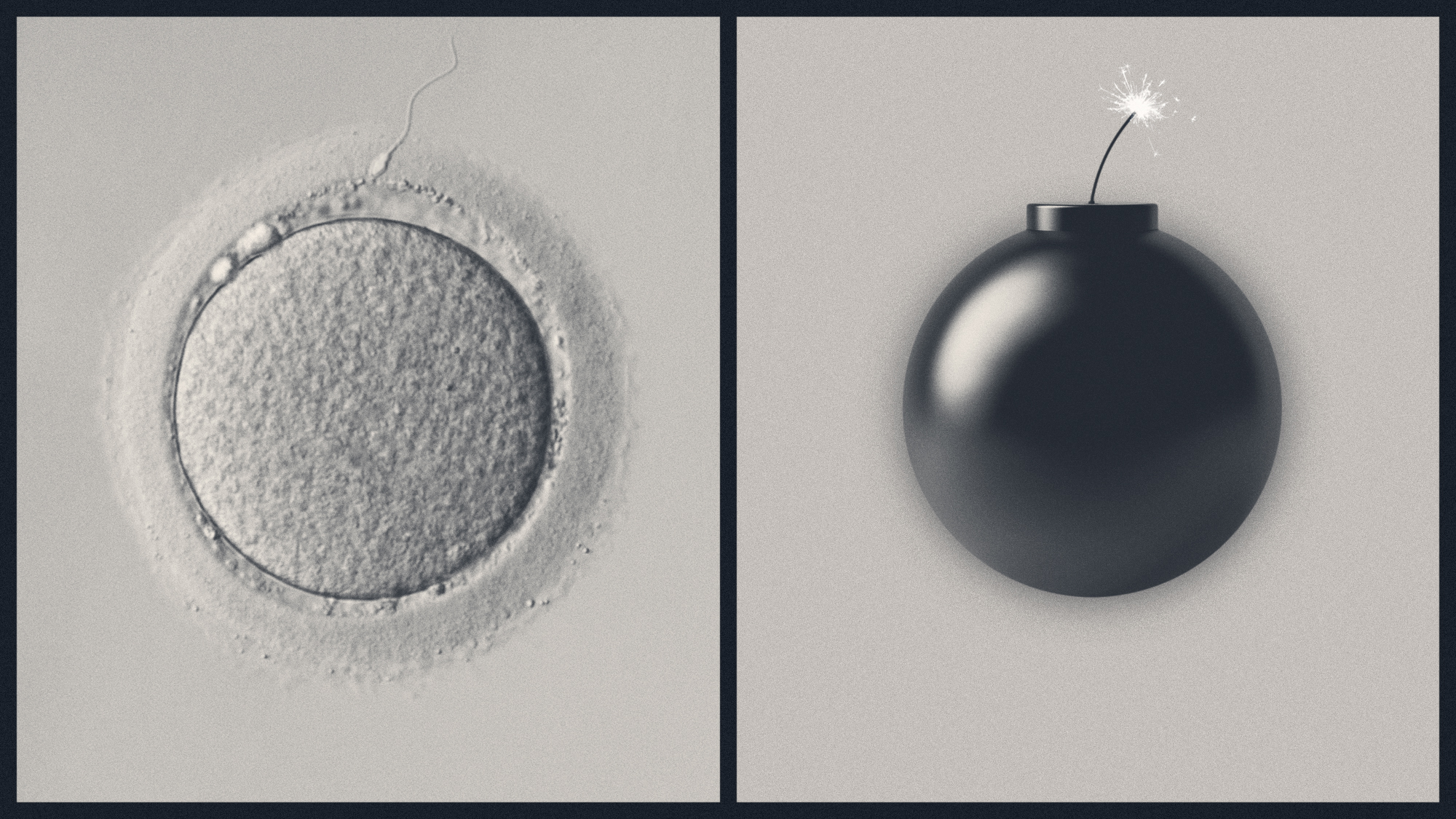

Does depopulation threaten humanity?

Falling birth rates could create a 'smaller, sadder, poorer future'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Governments around the world are trying new policies to boost birth rates. China this week said it will offer new parents a subsidy of $500 per child, for example. But what happens to humanity if the fertility crisis cannot be reversed?

Global fertility is now at the lowest rate in "recorded history," creating a potential "depopulation bomb," said Greg Ip at The Wall Street Journal. That worries economists Dean Spears and Michael Geruso, whose new book, "After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People," is an "impassioned case" against ignoring that trend. "Humanity could hasten its own extinction" if birth rates stay below replacement level, they said.

'Dramatically overstated'

People are "freaking out" about falling birth rates, said NPR. A "shrinking and aging population" will likely cause "even greater political instability," said The New Yorker's Gideon Lewis-Kraus to the outlet. That's because fewer people mean a smaller economy, which in turn means there's "less to go around."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Other experts caution against panic. America's birth rates are falling, but "we still have a natural increase" in the population, said the University of Colorado's Leslie Root to CBS News. That means there are still "more births than deaths."

Population collapse is "not imminent, inevitable or necessarily catastrophic," said Root and two other scholars at The Conversation. The United Nations projects the world will grow to 10 billion people by 2100, while the U.S. population is expected to grow by 22.6 million by 2050. It's "unrealistic" to believe that birth rates will "follow predictable patterns."

In America, there were about two births per woman in the 1930s — a rate that rose to 3.7 births by 1960 and dipped below 2 during the 1970s and '80s before rising in the '90s, only to drop again after the Great Recession. While there will be "changes in population structure" because of changing birth rates, those shifts have been "dramatically overstated," said Root.

"Global fertility trends are much worse" than U.N. demographers think, said Marc Novicoff at The Atlantic. And while it's true that birth rates have rebounded after past lows, "this time really does look different." That should be "alarming."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Japan's economy was 18% of world GDP in 1994, but its population got older — the median age is now 50 — and its economy is now "just 4% of the global economy." If birth rates do not pick up, the rest of the world will also experience a "smaller, sadder, poorer future."

A more peaceful world?

A possible upside is that the coming wave of depopulation could lead to a "Pax Geriatrica" in which "aging significantly reduces the likelihood of war," said Mark. L. Haas at Foreign Affairs. Governments will be "forced to attend to their aging populations," which will create societies "less capable and tolerant of waging war."

Falling birth rates will test a lot of assumptions, said Bloomberg. A lot of theories about the "way that the world works" were formed when "we just assumed the population would continue growing," said demographer Jennifer Sciubba. But rethinking old approaches may be difficult, said Bloomberg, as a "shrinking world would mean fewer innovators."

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

Did Alex Pretti’s killing open a GOP rift on guns?

Did Alex Pretti’s killing open a GOP rift on guns?Talking Points Second Amendment groups push back on the White House narrative

-

Washington grapples with ICE’s growing footprint — and future

Washington grapples with ICE’s growing footprint — and futureTALKING POINTS The deadly provocations of federal officers in Minnesota have put ICE back in the national spotlight

-

Trump’s Greenland ambitions push NATO to the edge

Trump’s Greenland ambitions push NATO to the edgeTalking Points The military alliance is facing its worst-ever crisis

-

Why is Trump threatening defense firms?

Why is Trump threatening defense firms?Talking Points CEO pay and stock buybacks will be restricted

-

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guarantee

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guaranteeTalking Points Zelenskyy says it is a requirement for peace. Will Putin go along?

-

Will California tax its billionaires?

Will California tax its billionaires?Talking Points A proposed one-time levy would shore up education and Medicaid

-

A free speech debate is raging over sign language at the White House

A free speech debate is raging over sign language at the White HouseTalking Points The administration has been accused of excluding deaf Americans from press briefings