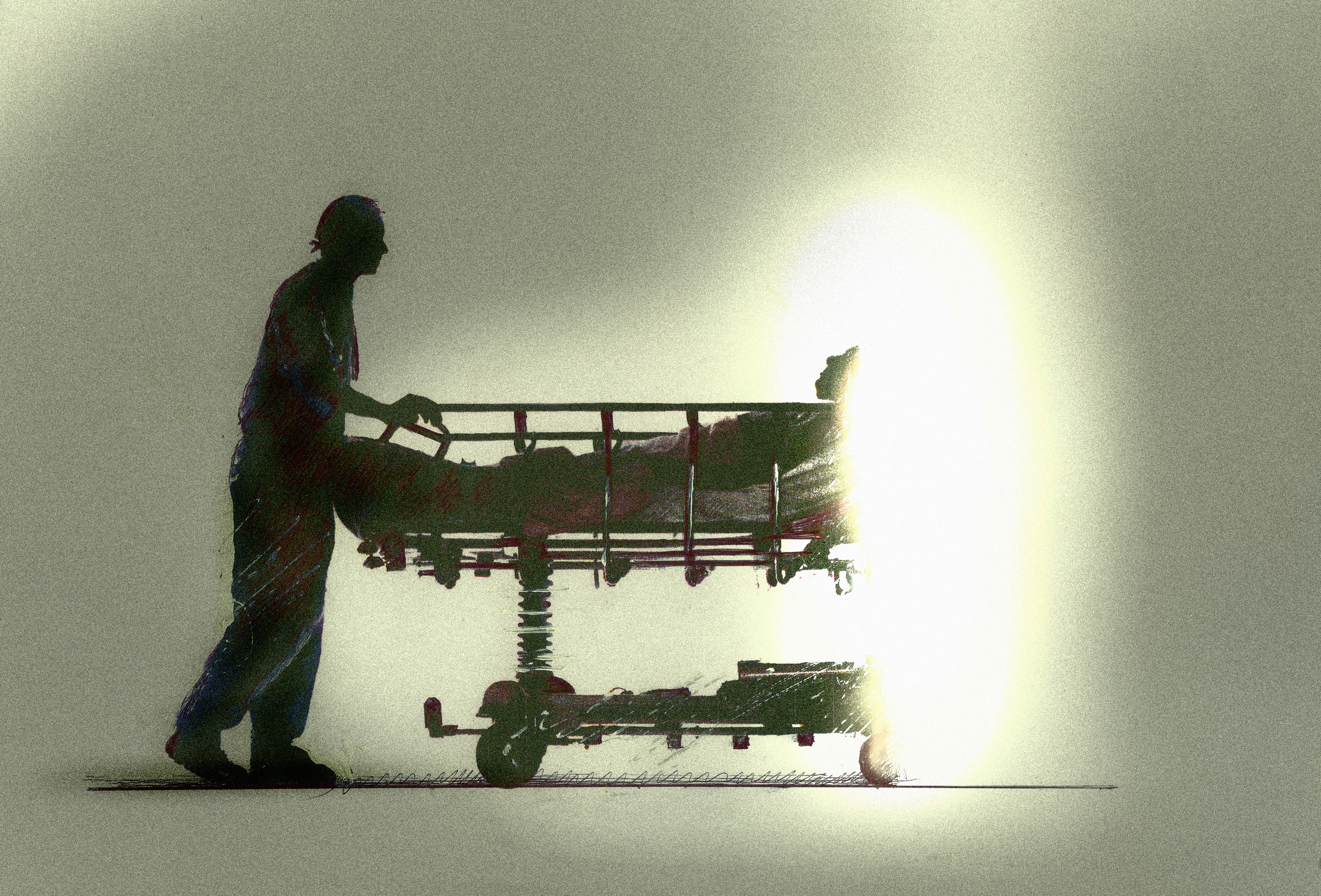

Why opposition to assisted suicide is inextricably tied to religion

You can't argue against assisted suicide without invoking God

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

More than abortion and gay marriage, assisted suicide is the issue in the culture war that most sharply divides those who view the world through a classically theistic (and especially Christian, and above all Roman Catholic) lens from those who do not.

The pro-life position can be defended in purely rational terms, given the murkiness around when human beings begin to possess dignity and rights. Opposition to gay marriage is more difficult to justify in non-theistic terms, but you can at least try to point to the meaning and social goods of traditional marriage and then attempt to show how they are inevitably undermined by redefining marriage to permit same-sex couples to wed.

But the arguments against permitting assisted suicide are different. They don't merely have a hard time gaining traction outside of a theistic view of the world. Without specifically theistic premises, they make no sense at all.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I'm not talking about arguments based on concerns about immoral consequences of permitting assisted suicide — like the fear that terminally ill and even permanently disabled people who are not facing imminent death will be pressured to kill themselves to ease social, fiscal, and familial burdens; or the worry that those suffering from depression and other forms of psychological torment will be hastened to their deaths along with those who are dying of fatal diseases.

These concerns deserve to be taken seriously, but they're not really objections to permitting assisted suicide in general. They're arguments in favor of administering it humanely and intelligently. If safeguards could be put in place to prevent these abuses, ensuring that people will be aided in ending their lives only when it can be determined that they are terminally ill and seeking to avoid pointless suffering, such arguments would lose their cogency.

Those who oppose assisted suicide in all cases cannot argue from consequences. They need to establish that it's always intrinsically wrong to take one's own life — and that's where theological premises become indispensable.

This was brought home to me in a new way while reading a long, moving essay by liberal blogger and journalist Kevin Drum in Mother Jones, titled "My right to die: Assisted suicide, my family, and me." Drum begins by recounting the story of his father-in-law, who took his own life near the end of a struggle with multiple myeloma, a cancer of the bone marrow. Drum then walks the reader through recent debates surrounding assisted suicide, culminating in California Gov. Jerry Brown's decision last October to sign a bill that will legalize it in the state later this year.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Only at the end of the essay does Drum reveal what regular readers of his blog already know: A little over a year ago he was diagnosed with the same cancer that struck his father-in-law. Drum also informs us that like his father-in-law, he may well choose to end his life once he's run out of treatment options. There is, however, one important difference between the two men: As a resident of California, Drum won't have to worry about legally implicating his doctors or any of his loved ones in the act of suicide.

I found Drum's essay to be powerful and poignant, but not all of my friends did. Those who oppose suicide in any form found the essay evasive and misleading. Yes, Drum notes in passing that some people make such arguments, but he doesn't lay them out with any care, let alone engage with them, let alone attempt to refute them.

Why not? I suspect it's because he isn't religious and finds such arguments irrelevant to his thinking about the issue.

I know how he feels. It seems patently obvious to me that although life is a very great good — the good that makes possible the enjoyment of every other good — it is not unconditionally good. If pain and debility reach intolerable levels with death an imminent inevitability, of course it's perfectly acceptable to bring it to an end — and for me, the person who is alive and suffering, to be the one who makes the decision to do so.

What are the arguments on the other side? They boil down to two, both of which are admirably summarized in the Catechism of the Roman Catholic Church.

The first (Par. 2280) claims that life is a gift given from God. We are "stewards" of it, not its "owners." It's therefore not properly in our power to dispense with it as we see fit. We must suffer and struggle through whatever comes our way, allowing death to happen of its own accord once medical efforts to preserve life have been exhausted. "Thy will be done."

The second argument (Par. 2281) simply asserts that suicide "offends love of neighbor because it unjustly breaks the ties of solidarity with family, nation, and other human societies to which we continue to have obligations." Just as God has the ultimate claim on our lives, which we cannot justly choose to sever, so families, neighbors, and even society as a whole have a claim on our lives, too.

The real-world implications of the second argument have been laid out with admirable clarity and bluntness in a response to Drum's essay published in The Federalist. If Drum eventually kills himself, author Daniel Payne writes, he will have cheated his wife out of "something that is hers by right: the chance to realize her wedding vows and her matrimonial commitment to the fullest possible degree by conferring upon her husband the last and most important measures of care and comfort she can give him. Parents who kill themselves cheat their children out of a similar blessing: the opportunity to repay, in however small and incomplete a way, the debt of life and succor all children owe their mothers and fathers."

Message: It would be selfish for Drum to end his own suffering and thereby deprive his family members of having to endure that suffering with him.

It's hard to read such statements and not conclude that those who make them sincerely believe that suffering is not only necessary, but even in some respects good, and certainly not pointless. When illness and debility strike we can seek aid, comfort, and solace from medical science, pain medication, and the promise of God's mercy after death. But in the end we cannot act to bring our suffering to an end. We have no choice but to persevere through it — because that's our lot, because we owe it to God and to everyone else, and because that's how God wants it.

Without these theological assumptions, the opposition to assisted suicide makes no sense.

Which is why the opposition to assisted suicide makes no sense to increasing numbers of people in our increasingly irreligious country.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day