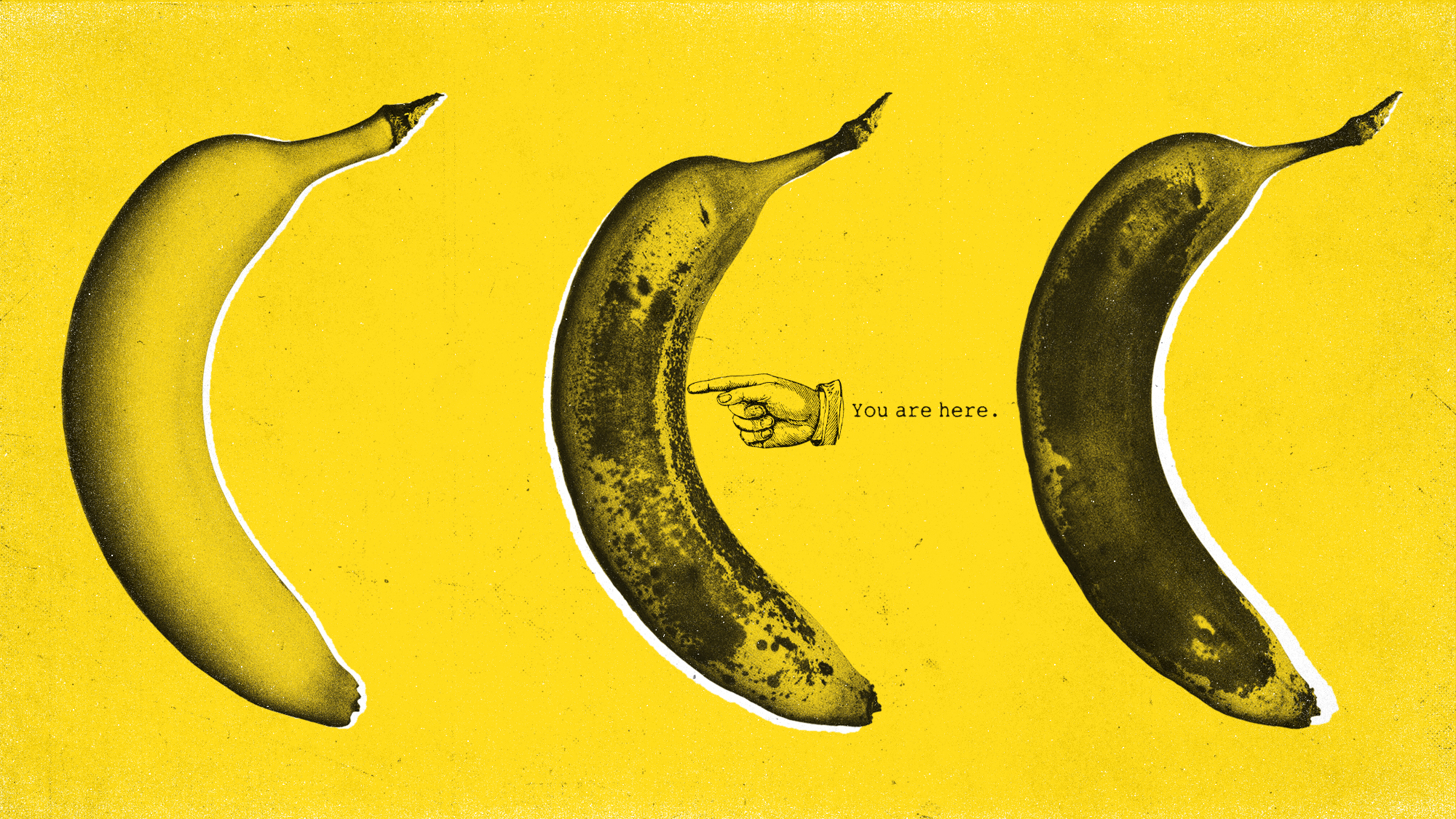

Not just a number: how aging rates vary by country

Inequality is a key factor

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Myriad factors drive how countries age at different rates, including health, social equity and the environment. Understanding these factors can allow for intervention to prevent rapid aging.

What factors affect aging rates?

A study published in the journal Nature Medicine examined 161,981 participants from 40 countries, including 27 in Europe, seven in Latin America, four in Asia and two in Africa, to determine their "biobehavioral age gap." This is the difference between a person's true chronological age and their age that was determined by examining their exposome or the "combined physical and social exposures experienced throughout life," said Nature.

"It's a very important study," said Claudia Kimie Suemoto, a geriatrician at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, to Nature. "It gives us the global perspective of how these dependent factors shape aging in different regions of the world." Some of the negative factors were more predictable, including medical ones like high blood pressure, hearing and vision impairment, heart disease, unhealthy weight, alcohol consumption, sleep problems and diabetes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There were also more surprising sociopolitical factors that contributed to aging. "Healthy aging, it turns out, is strongly tied to whether politicians act in your interest, having freedom for political parties, whether there are democratic elections and if you have the right to vote," said the BBC. "We never expected that," said Agustín Ibañez, the lead author of the study, to Nature. "Faster aging was also linked to lower national income levels, exposure to air pollution, social inequality and gender inequality," said Scientific American.

European countries had the highest levels of healthy aging, with Denmark topping the list. Egypt and South Africa had the fastest agers, and Latin American countries also showed faster aging than their European counterparts. Asian countries were in the middle.

There may also be more to the story, as countries in Africa, Asia and South America are largely underrepresented in the study. Additionally, the researchers only looked at data over four years, which is "very limited for the aging process," said Suemoto.

Can these factors be addressed?

"This is not a metaphor: Environmental and political conditions leave measurable fingerprints across 40 countries," said Hernan Hernandez, the co-first-author of the study, in a statement. The researchers tie the gap in aging to potentially high levels of stress. Political uncertainty means that "we are living in a world of despair," said Ibañez. "We don't think about the health impacts that this is going to have in the long run."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In some countries, women were more directly affected. "Despite advances in gender equality, women still face disproportionate disadvantages owing to caregiving roles, economic inequalities and health care access, potentially exacerbating accelerated aging," said the study.

On the bright side, certain factors were shown to protect against rapid aging, including "education, ability to perform activities of daily living and sound cognitive abilities," said Nature. Others included "physical activity, good memory and the ability to walk well."

Understanding this could allow for early intervention. "Cognition, functional ability, education, well-being, physical activity, sensory impairments and cardiometabolic conditions can be addressed through lifestyle changes, multicomponent interventions and public health policies," said the study.

However, risk factors had a "stronger impact than protective ones, and individuals in lower-income countries showed significantly accelerated aging regardless of individual socioeconomic status," said Morten Scheibye-Knudsen, an associate professor of aging at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, to the BBC.

To remedy this, systemic change is necessary. "Governments, international organizations and public health leaders must urgently act to reshape environments," Hernando Santamaria-Garcia, a co-first-author of the study, said in a statement. This could involve everything "from reducing air pollution to strengthening democratic institutions."

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

Growing a brain in the lab

Growing a brain in the labFeature It's a tiny version of a developing human cerebral cortex

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?Today's Big Question Cases are skyrocketing

-

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviews

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviewsTalking Points The guidelines emphasize red meat and full-fat dairy

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

The truth about vitamin supplements

The truth about vitamin supplementsThe Explainer UK industry worth £559 million but scientific evidence of health benefits is ‘complicated’