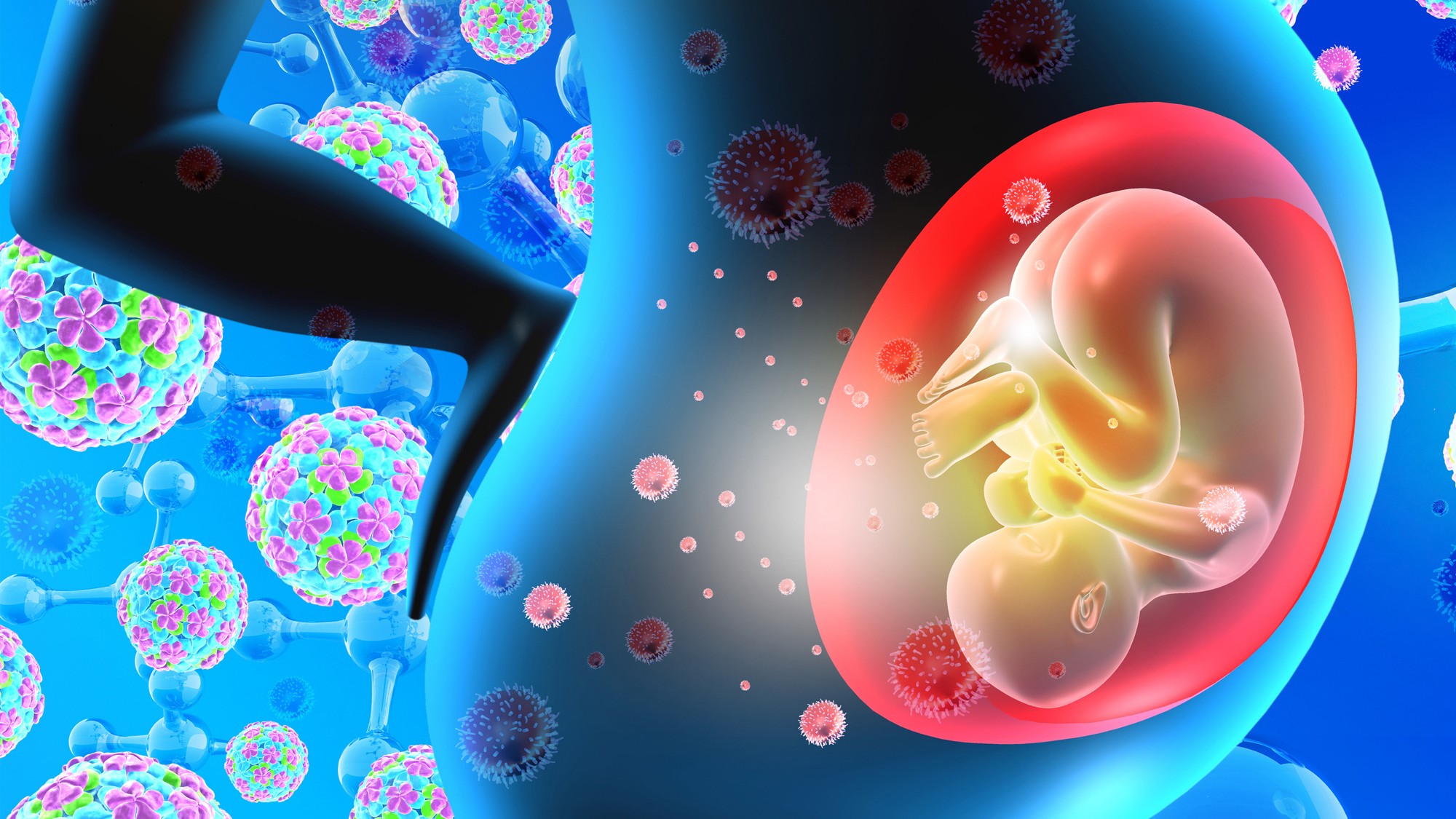

Cytomegalovirus can cause permanent birth defects

The virus can show no symptoms in adults

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) recently caused a 2-month-old girl in Pennsylvania to suffer severe hearing loss after it was passed to her in the womb. While the virus can exist in a person for life without showing any symptoms, it can also cause permanent disability in infants. Researchers are looking to create a vaccine for the disease, but it has proven tricky.

What is CMV?

CMV is a common herpes virus. More than half of adults have been infected with CMV by age 40, most with no signs or symptoms, said the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Like most other herpes viruses, CMV tends to "establish lifelong latency," said the CDC. "Once a person becomes infected, the virus remains latent and resides in cells without causing detectable damage or illness." It can spread in adults through contact with infectious body fluids, sexual contact, organ transplants and blood transfusions. The virus is usually very mild in adults. However, it could be deadly for immunosuppressed people. In rare cases, some who acquire CMV infection "may experience a mononucleosis-like condition with prolonged fever and hepatitis."

In babies, it is the "leading infectious cause of birth defects in the United States," and can have lifelong complications, said CBS News. Infants can contract the virus in the uterus or during birth. It is symptomatic in 10% of cases and can lead to "jaundice, fever and enlargement of the spleen and liver," said Britannica. "Whether symptomatic or not, CMV infections are a major cause of congenital deafness and have other long-range neurological consequences, including intellectual disability and blindness."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"If it's very early in pregnancy, sometimes the result can be very serious," said Jennifer Vodzak, a pediatric infectious disease doctor at Nemours Children's Hospital, to CBS News. "It can lead to a miscarriage and sometimes very serious birth defects for an infant." New evidence also suggests that CMV may not be entirely harmless in adults, even if there are no visible symptoms. Reducing the burden of CMV on the immune system "may reduce cases of diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure, particularly among non-Hispanic White (NHW) individuals," said a study published in the journal Lancet Regional Health.

What's the outlook for a vaccine?

Scientists are looking to develop a vaccine for CMV, though efforts have been unsuccessful. "If we don't know what weapons the enemy is using, it is hard to protect against it," said Jeremy Kamil, the senior author of a study about how CMV infects the body, in a statement. Luckily, the researchers have found a missing puzzle piece that represents one possible reason why immunization efforts against CMV have been so challenging.

The key is the virus' usage of a specific protein, which "becomes an alternative tool for breaking into cells lining the blood vessels and causing internal damage while simultaneously preventing the body's own immune system from recognizing the signs of infection," said the statement. "If we can develop antiviral drugs or vaccines that inhibit CMV entry, this will allow us to combat the many diseases this virus causes in developing babies and immune-compromised people," said Chris Benedict, the co-senior author of the study, in the statement. For now, newborn screening for the virus could allow for early intervention. Also, washing hands regularly and not sharing utensils, food or straws, especially when pregnant, can prevent the spread.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

Growing a brain in the lab

Growing a brain in the labFeature It's a tiny version of a developing human cerebral cortex

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue Tui after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?Today's Big Question Cases are skyrocketing

-

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UK

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UKThe Explainer The ‘Victorian-era’ condition is on the rise in the UK, and experts aren’t sure why

-

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviews

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviewsTalking Points The guidelines emphasize red meat and full-fat dairy

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

The truth about vitamin supplements

The truth about vitamin supplementsThe Explainer UK industry worth £559 million but scientific evidence of health benefits is ‘complicated’