Babies born using 3 people's DNA lack hereditary disease

The method could eliminate mutations for future generations

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

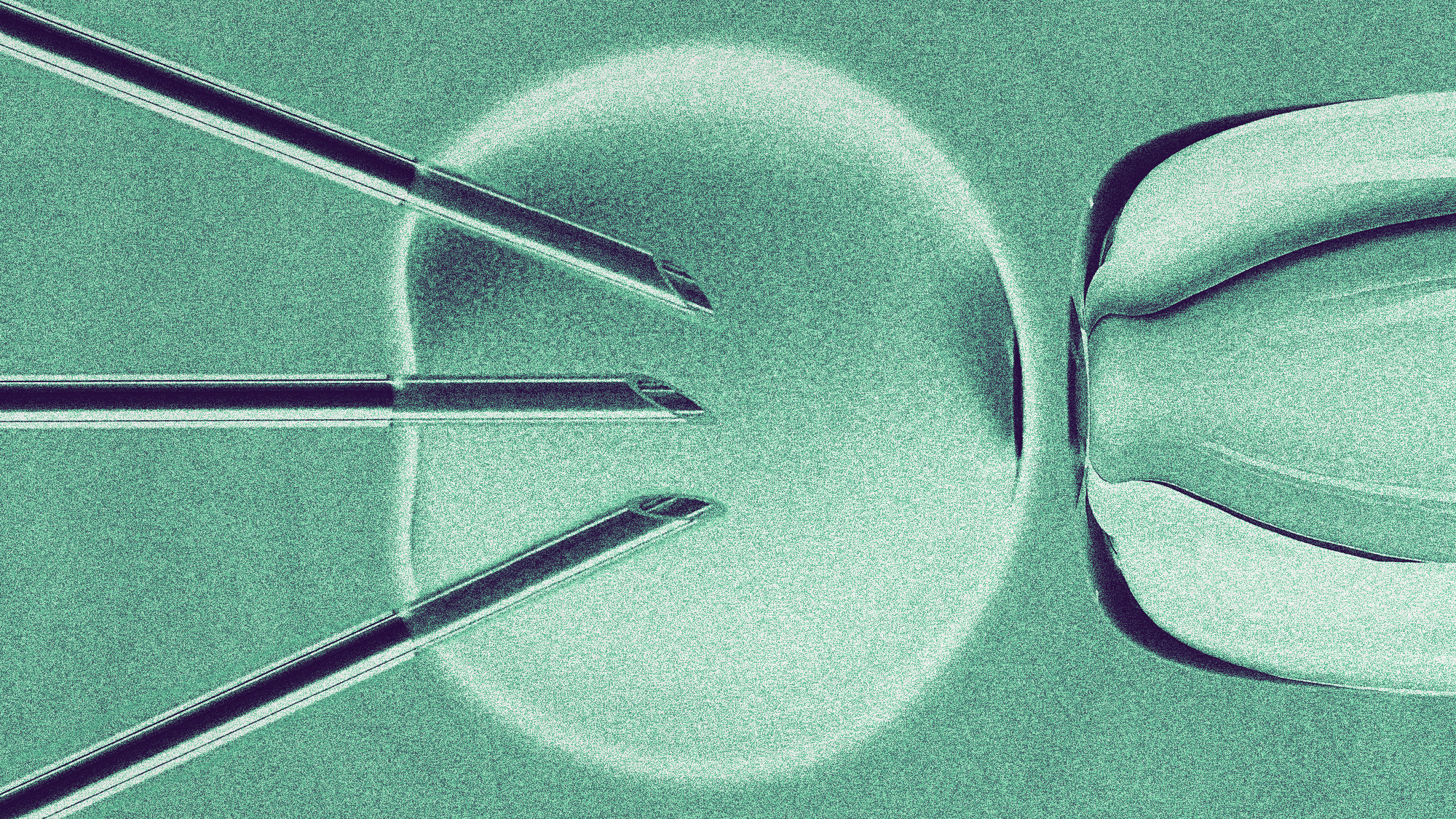

Mitochondria are widely known as the "powerhouse of the cell" because of their ability to generate energy in the body and convert nutrients from food. With such an essential job, mutations in mitochondrial DNA can lead to debilitating consequences. But a pioneering IVF method could prevent babies from inheriting defective mitochondrial DNA altogether and even permanently change the gene for future generations.

DNA a new way

Eight babies in the U.K. were born without rare hereditary mitochondrial diseases and have continued to develop normally thanks to an experimental IVF technique, according to two papers published in the New England Journal of Medicine. "All babies were healthy at birth, meeting their developmental milestones, and the mother's disease-causing mitochondrial DNA mutations were either undetectable or present at levels that are very unlikely to cause disease," said a press release about the studies.

This IVF technique, known as pronuclear transfer, uses the majority of DNA from a man and woman and a small portion from another donor egg, also called mitochondrial donation treatment. The process involves "transplanting the nuclear genome (which contains all the genes essential for our individual characteristics, such as hair color and height) from an egg carrying a mitochondrial DNA mutation to an egg donated by an unaffected woman that has had its nuclear genome removed," said the press release. "The resulting embryo inherits its parents' nuclear DNA, but the mitochondrial DNA is inherited predominantly from the donated egg."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The technique has been legal in the U.K. since 2015, and the first use of it occurred in 2016. But this is the first proof that it can lead to children being born without the incurable mutations.

Approximately one in 5,000 children is born with mitochondrial mutations each year. Defective mitochondria "leave the body with insufficient energy to keep the heart beating" and can cause "brain damage, seizures, blindness, muscle weakness and organ failure," said the BBC.

Mitochondrial DNA is largely inherited from the biological mother's DNA. And while there's no cure for mitochondrial defects once inherited, this method could prevent it from being passed on at all.

Babies by design

The use of gene editing techniques like pronuclear transfer has been a subject of controversy. Those opposed say it's a "step too far," said the BBC. Some fear it will "open the doors to genetically modified 'designer' babies."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's also "impossible to know the impact these sorts of novel techniques might have on future generations," said The Associated Press. However, "women at risk for transmitting severe [mitochondrial DNA] disease to their children should have the opportunity to make informed choices about their reproductive options," said one of the papers.

The use of pronuclear transfer is currently not allowed in the U.S. "largely due to regulatory restrictions on techniques that result in heritable changes to the embryo," said Zev Williams, the director of the Columbia University Fertility Center, to the AP. "Whether that will change remains uncertain and will depend on evolving scientific, ethical and policy discussions." Mitochondrial donation as a "choice for women with a heritable pathogenic [mitochondrial DNA] variant will only be established with the availability of additional data," said the paper.

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.