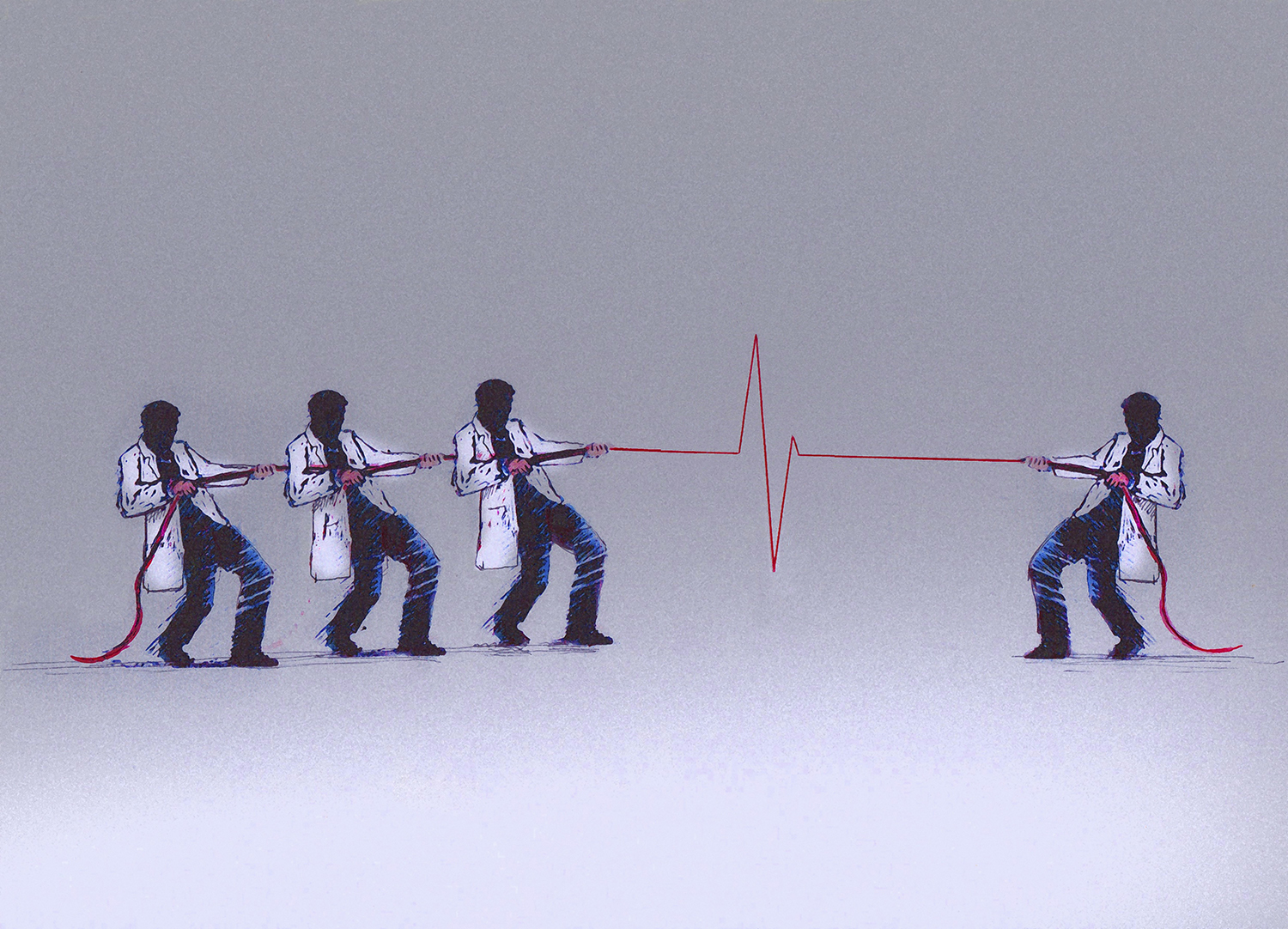

This doctor helped the dying end their lives with dignity. Then he was diagnosed with cancer.

How Dr. Peter Rasmussen made his final choice

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Peter Rasmussen was always able to identify with his patients, particularly in their final moments. But he saw himself especially in a small, businesslike woman with leukemia who came to him in the spring of 2007, not long before he retired. Alice was in her late 50s and lived outside Salem, Oregon, where Rasmussen practiced medical oncology. Like him, she was stubborn and practical and independent. She was not the sort of patient who denied what was happening to her or who scrambled after any possibility of a cure. As Rasmussen saw it, "she had long ago thought about what was important and valuable to her, and she applied that to the fact that she now had acute leukemia."

From the start, Alice refused chemotherapy, a treatment that would have meant several long hospitalizations with certain suffering, a good chance of death, and a small likelihood of truly helping. As her illness progressed, she also refused hospice care. She wanted to die at home.

Six months after Rasmussen started seeing Alice, he wrote in her chart about his admiration for her and her husband: "Together they are doing a wonderful job not only preparing for her continued worsening and imminent death but also in living a pretty good life in the meantime." But there were more fevers and bleeding and weakness. In late January, she asked him to write her a prescription for pentobarbital.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Three days later he arrived at her farmhouse with four vials of bitter liquid. Though the law didn't require it, he liked to bring the drug from the pharmacy himself, right before it was to be used, so that there would be no mistakes.

Over nearly three decades as a physician in Oregon, Rasmussen had developed many strong beliefs about death. The strongest was that patients should have the right to make their own decisions about how to face it. He remembers the scene in Alice's bedroom as "inspiring, in a sense" — the kind of personal choice that he'd envisioned during the long, lonely years when he'd fought, against the disapproval of nearly everyone he knew and all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, for the right of terminal patients to decide when and how to die.

By the time he retired, Rasmussen had helped dozens of patients end their lives. But he kept thinking about Alice. Her pragmatism mirrored the image he had of how he would face such a diagnosis. But while he had often conjured that image — had faced it every time he walked a dying patient through a list of inadequate options — he also knew better than to fully believe in it. How could you be sure what you would do before the decisions were real?

"You don't know the answer to that until you actually face it," he said later — after his own diagnosis had been made, after he knew that he had cancer and that he would soon die. "You can say you do, but you don't really know."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The knowledge hid in the back of Rasmussen's mind — a flitting worry you don't look at directly — for a few days before he really comprehended it.

He was on his way home from a meeting of the continuing-education group he had joined after his retirement. One of the group's members had asked him to let the others know that she had been diagnosed with a glioblastoma — a type of brain tumor whose implacable aggression he knew well. A glioblastoma can cause seizures, memory loss, partial paralysis, even personality changes. You can treat the tumor with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, but it will always come back, often in more places. The timeline can be uncertain, but the prognosis never is. The median period of survival after diagnosis is seven months.

As Rasmussen drove away from the meeting, his left hand was draped on the wheel of his Tesla. It felt, as it had for several days, oddly numb, as if he'd been holding a vibrating object for too long. He'd ignored the feeling, chalking it up to spending too much time power-washing pinecones off his cedar-shake roof.

Maybe it was what had happened at the meeting, or the clarity of a wandering mind. All at once he focused on the sensation — on how localized it was, on the fact that it hadn't gone away — and he knew. Something was wrong. "I've either got MS," he thought, "or I've got a brain tumor."

Instead of driving home he went straight to an urgent-care clinic, where a doctor sent him to the E.R., where another doctor gave him an MRI, which showed a tumor. It was, he learned later, a glioblastoma about an inch in diameter. Barring an accident, it would be the thing that killed him, sometime in the suddenly too near future.

Eight days after his MRI, Rasmussen went to the hospital to have part of his skull cut away and his tumor sliced out. He had considered whether having surgery violated his usual advice about not wasting one's final months seeking painful and unlikely cures, but because his tumor was localized and fairly accessible, he and his surgeon decided that the odds were good enough to try.

The surgery was a success — though Rasmussen lost the use of his left arm, the entire visible tumor was removed, and he was able to leave the next day. Of course, success was only a slower form of failure: He was still going to die. He never let himself, or anyone around him, forget that his reprieve was temporary. "It's not if I pass away," he corrected his lawyer, his accountant, his friends. "It's when I die."

Before he retired, Rasmussen had often tried to help his patients and their families think of the process of dying as an opportunity, a chance for clarity and forgiveness, for thoughtful, meaningful goodbyes. He hoped to hold on to that belief for himself. When he pictured a good death, the image was simple: calm and peace, without much physical suffering, and his family with him in the house where he'd lived for 18 years with Cindy, his wife; where the kids had grown up; where the windows looked out on his bird feeders and his flowers.

It wasn't time yet. Five months after the surgery, he stopped chemo and radiation. He began to feel better, stronger, and was even able to use his left hand a little. Still, every time he had a headache or nausea he wondered whether the tumor was growing back. But whenever he started to feel sorry for himself, he'd administer a stern mental shake: "We all die," he'd tell himself. "It's never fair to anybody. So buck up."

Privately, he had no idea whether or not he'd take advantage of Oregon's assisted suicide law. He consulted a list that he'd kept of his Death With Dignity patients. At first most had been urgent cases: people with all kinds of terminal diseases, who were suffering intensely and wanted to take the drug right away. As time passed, people began coming to him sooner after their diagnoses, before they knew how their diseases would develop. Some only asked questions, and others wanted to have the pentobarbital handy, a just-in-case comfort that made them feel more in control. The majority of his patients never took the medication.

Every death was different, though most had details in common: reminiscing in advance, goodbyes filled with love, family members saying that it was OK to stop struggling. There was the death with the Harley-Davidsons: He'd pulled up to the house and there were motorcycles everywhere, people in leather drinking beer on the lawn, just the party his patient wanted.

Of course, not everyone wanted a party, and he respected that too. Often there were only a few family members, and sometimes it was just him and the patient, alone together at the last. Only once did someone ask to die completely alone, in quiet privacy behind the closed door of a bedroom.

He remembered a woman whose mastectomy had not stopped her breast cancer from metastasizing to her lungs. Her huge family came in for the weekend. They had a picnic on Saturday, went to church on Sunday, and then all the kids and grandkids filed through her bedroom to say goodbye. He waited outside the door until they were done and then he brought her a dose of pentobarbital. She drank it and died. That one stuck with him: "It was about as ideal a death as I possibly could have imagined."

In July of last year, Rasmussen went in for a new MRI. The scan showed the tumor, the same size and back in the same place it had been the year before. He consulted with his surgeon, who told him that the tumor was once again a good candidate for removal. Rasmussen would most likely lose the use of his left arm altogether, but if all went very well, he would have a one-in-three chance of living to the second anniversary of his diagnosis.

"I'll leave tomorrow for the trip," he told Cindy after meeting with the surgeon — meaning a cross-country road trip that he'd been talking about. Cindy was stunned. She hadn't thought he'd actually go. But he was adamant, and then he was gone.

He drove east through Idaho, Montana, South Dakota, along long, open stretches of quiet road. He brought recorded lectures to keep him company: one about St. Francis, a series on the Higgs boson, and a particularly interesting lecture about gnosticism.

As he drove, he tried to visualize what his life would be like if he underwent surgery or stopped treatment altogether. He imagined losing more of the use of his left side and eventually ending up in hospice, bedbound. That part didn't bother him so much. He knew it was coming no matter what. But he didn't like thinking about stopping treatment, not yet. It was too passive, too final. It just made him too sad.

Somewhere around the ninth day of his trip, he had a thought that excited him. "The task of learning to be a hemiparetic person," of living with paralysis on his left side, could be an adventure, another learning experience. "To take on a challenge is always satisfying," he explained later. Relief washed over him. He had made a decision.

He wasn't planning to have the surgery right away, but an hour after arriving home he had a seizure. Four days later he was back in the O.R., and surgeons were once again scooping a tumor from his brain. He woke to find himself paralyzed not just in his arm, but throughout the left side of his body. For days he was noticeably quiet. After three days he moved to a nursing-care facility. The first morning there, he called Cindy to tell her that he'd been very sad the night before. "Did you cry?" she asked.

"No, I didn't cry," he replied. "But I was mourning the loss of my independence."

On Oct. 1, he was admitted to the hospital for a new MRI. The results showed that his tumor had not only grown back but expanded into the middle of his brain. "I want to go home," he said.

Cindy set up a hospital bed in the living room looking out over his gardens. His stepchildren arrived from New York and Seattle. For four nights Cindy and the kids stayed by his bed, each night thinking it would be the last. Instead, he grew stronger for a time — a month that Cindy calls "one of the most meaningful experiences I've ever had and probably will ever have." He visited with friends and family, watched a slide show of old pictures, listened as music therapists played his favorite songs on the ukulele.

Rasmussen had already started the paperwork for Death With Dignity, but he didn't want to add the final touch, his own signature. Near the end of October, he was speaking only a few labored words at a time. One day he asked Cindy to help him stand so he could get up to go to the bathroom, something he hadn't done in weeks. He was so weak and frail that Cindy told him it was impossible. She says she saw the realization happen then: "This is it."

On Oct. 29, Rasmussen signed the paperwork and his siblings flew in from Wisconsin, Illinois, and North Carolina. He planned to take the drug the next week, after what Cindy calls "a memorial service while he was still alive." Sixteen people gathered around Rasmussen; one by one they told him what he had meant to them and what they would remember about him.

He was alert but not talking much on the morning of Nov. 3. His family intertwined their arms in a circle around him and put piano music on the stereo. He raised the cup of secobarbital mixed with juice — papaya, orange, and mango, his favorite — and drank it down. His eyes closed. Cindy, sobbing, realized how similar the scene was to what he used to describe when he came home from someone else's death. "It was awful," she says. "But at the same time, I was glad that he was able to end his life on his terms."

Half an hour later, he quietly stopped breathing.

Copyright © Harper's Magazine. All rights reserved. Excerpted from the January 2016 issue by special permission.