Why Friends is still so popular

What explains millennials' obsession with a 1990s show about 20-somethings who hang out in a coffee shop? It's nostalgia for a simpler time — before social media.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When the TV critic Andy Greenwald, who is 38, returned to his high school near Philadelphia last May to speak to students about his job, he wondered how it would go. After all, today's students are a digital generation who have only a vague association with the concept of "TV." Sure enough, when Greenwald mentioned his job to them, one student in the group asked, "So what does that mean? Do you, like, watch Netflix?" Greenwald said, sure, he watches Netflix, since watching original streaming programming — on Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, wherever — is all part of covering the complex new television landscape. Then he asked the teenagers if they watched Netflix. They said, enthusiastically, yes. So he asked them what they liked to watch on Netflix. They said, enthusiastically, Friends.

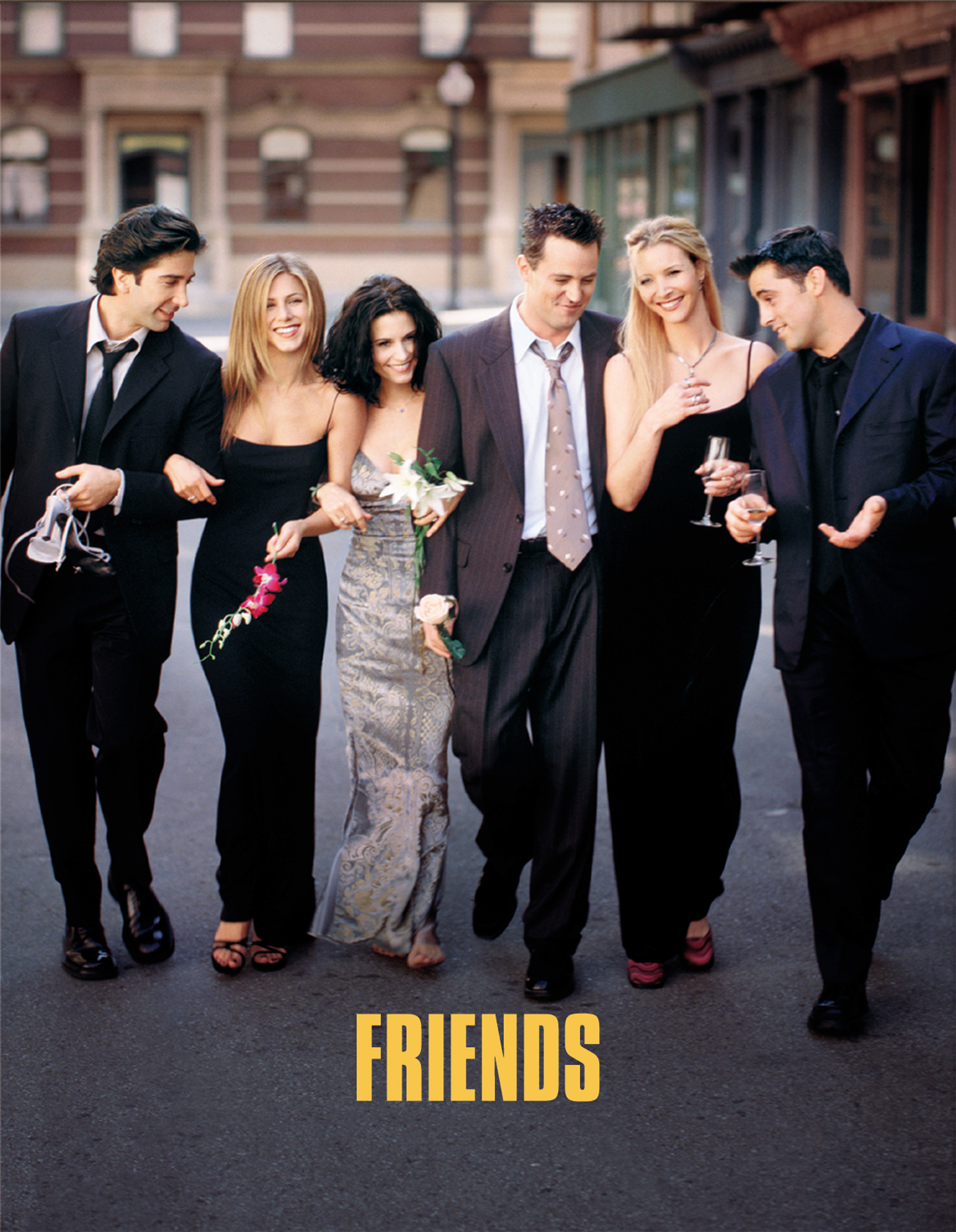

You remember Friends, right? Chandler, Monica, Joey, Phoebe, Rachel, Ross, and, fleetingly, that monkey? Central Perk? "We were on a break"? The show that feels, in its way, as iconic a relic of the 1990s as Nirvana, Pulp Fiction, and a two-term Clinton presidency that the Onion later cheekily described as "our long national nightmare of peace and prosperity"?

Friends was not only born of that era but may in hindsight embody it more completely than any other TV show. Sexier than Cheers, less acerbic than Seinfeld, Friends existed at the sweet spot of populist mass entertainment and prescient pop escapism. If you were alive and sentient in the 1990s, you already understand this. In fact, if you were in, or near, your 20s back then and ever found yourself seated in a quirkily named coffee shop with a bunch of your own friends, you might have had the conversation: Which Friend are you?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But while Friends inarguably excavated the zeitgeist, it was a very different geist, in a very different zeit. For starters, the show's run, from 1994 to 2004, corresponds almost exactly with that transformational decade when people went from signing up for this weird new thing called "email" to signing up for this weird new thing called "Facebook." The world of Friends is notable, to modern eyes, for what it encompasses about being young and single and carefree in the city but also for what it doesn't encompass: social media, smartphones, student debt, the sexual politics of Tinder, moving back in with your parents as a matter of course, and a national mood that vacillates between anxiety and defeatism. (Not to mention the absence of any primary characters on the show who aren't straight or white.)

Which is why you might expect that Friends, like similar cultural relics of that era, would be safely preserved in the cryogenic chamber of our collective nostalgia. And yet, astonishingly, the show is arguably as popular as it ever was — and it is popular with a cohort of young people who are only now discovering it. Which is weird.

I'm sitting on the couch. The actual couch. It's inside the actual Central Perk café set, which is now part of the Warner Bros. studio tour in Burbank, California. The couch — this familiar overstuffed orange sofa — is, for many people, the main attraction of the tour. Before our group set off in an elongated golf cart to patrol the studio's back lots, the guide asked if there were any Warner Bros. shows or movies that people were particularly interested in seeing. "Friends!" came the first, quickest answer. "Friends," came the second. Another woman from the back called out "Friends!" before someone finally said "Harry Potter." Later, I asked the guide if that was a typical reaction. "I'm not going to lie," he said. "Friends is definitely the biggest attraction."

At Stage 48, it's not unheard of for people to get engaged on the couch; a guide told me it happened just a few weeks ago. I asked him if any visitors — some of whom have traveled from across the world on a kind of pilgrimage — ever have unusual reactions when they finally sit on the couch. "Oh, yes," he said. "People cry. All the time."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It is, of course, slightly strange that a 20-year-old sitcom still retains such a magnetic appeal; for example, Warner Bros. also produced ER, which ran for 15 seasons, but there's no opportunity, nor likely much demand, to have your photo taken on that show's authentic gurney, let alone get engaged on it. Yet Friends' popularity seems to be on the rise. Between its various syndicated airings, the show still draws a weekly audience of 16 million in the U.S., a big enough viewership to make it a viable hit on current network TV (and that's not even including streaming). In the U.K., ratings for Friends repeats are growing, up more than 10 percent in 2015 from the previous year. And on Jan. 1, 2015, the entire run of Friends — all 236 episodes, or 88 hours' worth — became available on Netflix; the company paid an undisclosed sum for the rights to stream it. (The best industry guess put the price at roughly $118 million.)

One person who's noticed a resurgence in Friends-mania is someone with some expertise on the subject: Marta Kauffman, who was co-creator of the show with David Crane. "It blows my mind," she says. "Not only that people are still watching but that people still connect to it. I have a 17-year-old daughter, and recently someone at her school asked her, 'Hey, have you seen this new show called Friends?'"

There are, of course, current shows about the modern lives of young urbanites, any of which would presumably be more relatable to young viewers — but for some, those shows, in all their circa-2016 grittiness, are a little too real. "I watch shows like Girls and it feels like the raw reality of life," says Kayla Yandoli, an intern at BuzzFeed who along with her sister, a BuzzFeed staff writer, writes a lot of Friends posts. "Friends is like the sitcom version of life."

More than once, when asked about the appeal of the show, a 20-something quoted back to me an iconic line that Monica says to Rachel in the pilot: "Welcome to the real world. It sucks. You're gonna love it." They explain that they've adopted the line as a kind of generational motto. Which the line was intended to be, sort of — except for a different generation. No matter: The notion has an enduring appeal, especially given that for 20-somethings now, the real world seems suckier than ever. "The '90s were a great time," says Chris Mustacchio, who is 24, works in New York, and estimates he's seen every episode of Friends more than five times. Like more than a few people I talked to, he describes habitually falling asleep to the show. "If you think about it, back then there was little conflict. It was pre-9/11. You could smoke on airplanes, you could smoke in restaurants. Bill Clinton was in the White House. He was the best president of all time!"

"Post-9/11, the show became more popular," says Kauffman. "And I think part of the reason is because it was optimistic. And certainly, with what's going on politically right now, this can feel like a darker time."

I lived through Friends, once. I was 23 years old when the show premiered, and I watched the Friends pilot under protest, prodded by my little sister. To my slacker-hardened sensibility, the show looked to be, at first glance, an anodyne attempt to chase "the youth" and cash in on the sour magic of Seinfeld. But I watched. And I laughed. And I kept watching. And eventually I had the conversation. (I was Chandler.)

Now I'm in my 40s and there is very little about the current world — especially culturally speaking — that reminds me of the world of Friends. When I was in college, people were still brandishing dog-eared copies of Neil Postman's anti-TV polemic Amusing Ourselves to Death; now TV has shrugged off its consensus reputation as a purveyor of widespread idiocy to become the most celebrated artistic form of our time. I currently have a palm-size computer in my pocket that's smarter than Deep Blue, the supercomputer that beat Garry Kasparov at chess in 1997 — and on which, it turns out, I can stream Friends in its entirety. In 2016, we tweet. We text. We Vine. We swipe right. Friends, of course, reflects none of this. (Mentions of the internet are limited to very occasional high jinks, like Chandler meeting a woman online who turns out to be his ex-girlfriend Janice.)

And, I admit, I do find myself occasionally nostalgic for that moment right before the internet became all-encompassing, when you could only ever hang out with your friends in real life — and you never said IRL, because what other life would you be talking about, if not your "real" one? I feel nostalgic for the '90s in the exact way that every generation feels nostalgic for the era that coincides with its own youth. I'm not surprised or particularly apologetic to feel this way.

I am, however, surprised that a whole new generation — all of whom are presumably much more tweet-, text-, Vine-, and Tinder-friendly than I am — is feeling the same way, and expressing it by embracing the very show my generation once embraced. After all, each generation has the right to bury the icons of its forebears, just as we in our Screaming Trees T-shirts once hated on the Eagles. Instead, these kids are going to Friends trivia nights at Asian-fusion tapas bars, and starting podcasts devoted to recapping and analyzing every single episode of the show.

"Part of the appeal is wish fulfillment," says Kauffman of the show's continued appeal to younger viewers. "And another part of it is because they're on social media all the time, so I believe they crave human contact. They crave intimacy, and intimate relationships. They're looking at screens all the time." The world of Friends is recognizable, yet devoid of today's most ardent anxieties. On Friends, "in their free time, they all get together in the coffee shop to chat and catch up," says Stephanie Piko, a 21-year-old fan of the show. "Where nowadays we'll catch up really quickly, but everyone's always on their phones. Back then, it's more of a person-to-person relationship, instead of through technology." In hindsight, that era seems idyllic by comparison: a fantasy life where friends gather on a sofa, not on WhatsApp.

I asked Elizabeth Entenman, a 27-year-old Friends fanatic, if you could make a version of Friends about the 20-somethings of today. "No," she said, "because you wouldn't find six people doing nothing in the same room." Or if they were, they'd all be on their phones, seeing what else is out there. On modern sitcoms like Netflix's Master of None or Love, the agony of the slowly answered, or never answered, text is a recurring plot device, so familiar and realistic that it makes us squirm along with the character onscreen. There's no escapism to be had there. Instead, it reminds us of the sad modern paradox: Knowing you can reach out to anyone at any time hasn't actually brought us any closer together.

And so the central pleasure of watching Friends — the feeling of being cosseted in a familiar place, free of worries, surrounded by friends — has never been quite so longed for as it is now. Paulina McGowan, 21, was born in 1994, the year Friends debuted. Watching it now, she says, "It would be awesome to be alive back then, when everything didn't seem so intense. It just seemed really fun."

After the Warner Bros. tour, having hoisted myself up from that magical couch, I found it impossible while driving around L.A. to escape — or ignore — the pop hit "Stressed Out," by Twenty One Pilots (current YouTube views: 152 million and counting). The song features the telling refrain: "Wish we could turn back time, to the good ol' days / When our momma sang us to sleep / But now we're stressed out." Eventually, we all grow up and move out of range of our momma's voice. But I couldn't help but think of all those young people who told me they now like to fall asleep to Friends.

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared at Vulture.com. Reprinted with permission.