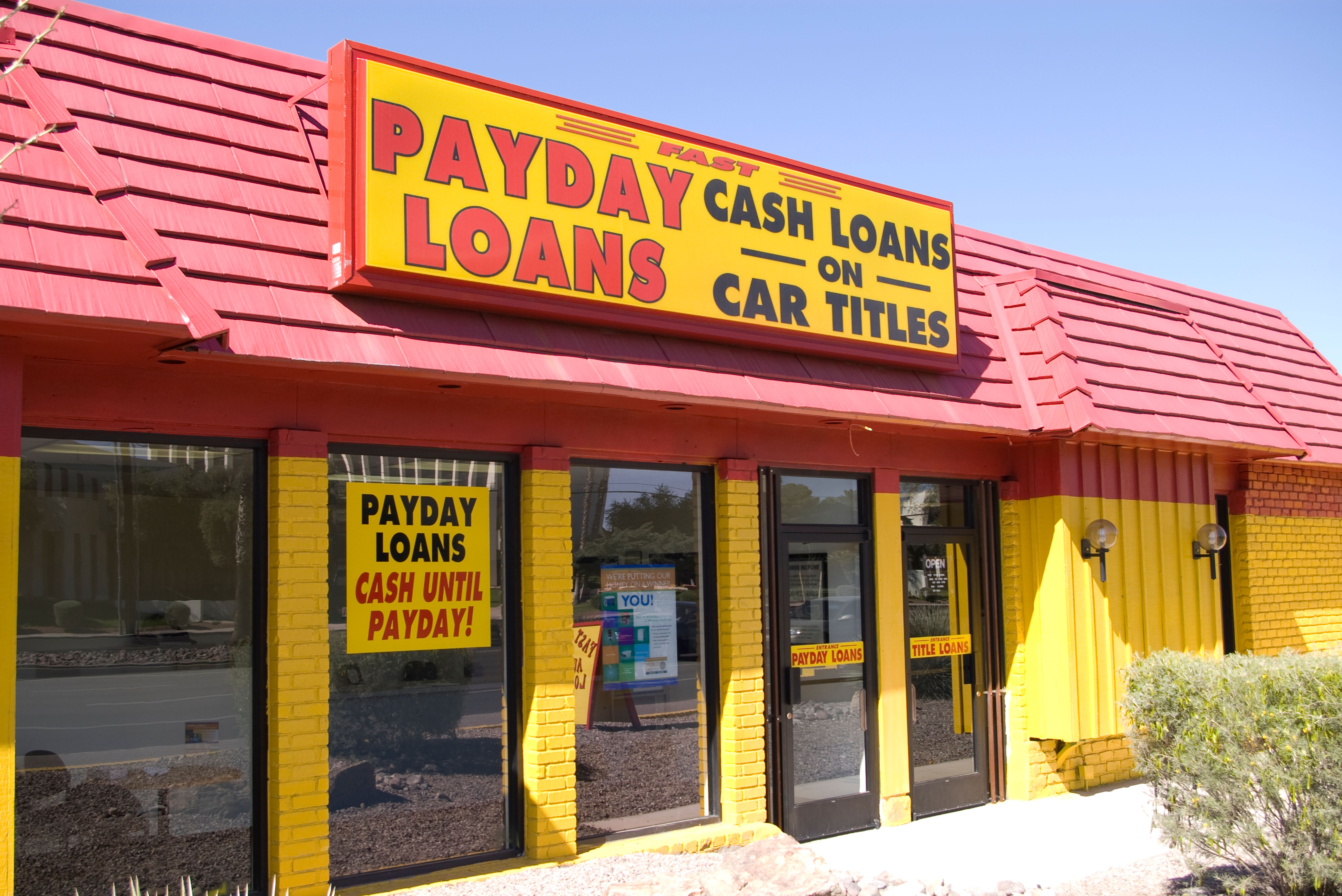

Two cheers for the end of payday lenders!

Payday lenders basically prey on the poor. The only question is, will anything replace them?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Payday loans have been in the government's crosshairs for a while now. On Thursday, it announced it's pulling the trigger.

The customer base for the payday loan industry is overwhelmingly poor and working class. The loans themselves tend to be small — just a few hundred dollars — and short-term. They come with extraordinarily high interest rates, and almost two-thirds of them are regularly rolled-over by their customers — extended with another loan, until the person owes more than they initially borrowed, creating what President Obama once decried as a "cycle of debt."

The watchdog agency that oversees the industry, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), can't cap interest rates directly. So instead it laid out three new rules on Thursday: Payday lenders must do additional checks to make sure a borrower can make payments while still meeting basic living and financial expenses; there will be new and significant time constraints on when and how often debt can be rolled over; and there will be limits on when and how lenders can deduct fees from borrowers. (It's typical for a payday lender to gain access to a borrower's checking account as part of the deal.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The rules still have to go through a review process. But this has been in the works for a while, and by now the debate over payday lenders has settled into a familiar rut. Critics call their business practice predatory, and accuse them of trapping poor and struggling Americans in permanent debt. Defenders insist payday lenders use this business model because it's the only way they can turn a profit, and if they go away, there will be no one left to extend credit to the poor when they need it.

What no one seems to notice is that all these things can be true at the same time.

Business models that largely serve poor customer bases have to be fundamentally different than business models that serve the middle class or the wealthy. Being poor, their paychecks aren't only more meager, but often more sporadic — the poor are much more likely to be employed part time, or by employers who schedule them at the last minute. And because their personal and family budgets are so precariously balanced, any unexpected expense, however small — like a parking ticket or a minor injury — can set off a chain reaction of further missed bills and new fees.

A lot of financial services providers and major banks deal with this reality by simply avoiding poor customers and their communities. So about 68 million Americans don't have a savings or checking account at all. They wind up losing large portions of already-small paychecks to check-cashing fees the rest of us never have to deal with. They have enormous difficulty getting credit cards. And, of course, banks tend to not make the kinds of small-bore, several-hundred-dollar loans that payday lenders specialize in precisely because they aren't worth the trouble.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is the market need payday lenders have stepped in to fill. And precisely because the finances of their customer base are so fragile and sporadic, payday lenders must rely on sky-high interest rates and a certain number of customers who perpetually roll over their debt. These lenders can't remain profitable otherwise. Even the fact that they don't run checks on their customers' financial health is due to their inability to afford the extra paperwork costs.

The CFPB itself estimates its new rules will cut payday loan volume by at least 55 percent, and that payday lenders' $7 billion cumulative annual revenue from fees will drop a lot as well.

But to conclude from this that payday lenders are actually the good guys, and the CFPB should lay off, would be obtuse. The CFPB's new regulations are a step in the right direction. But we also must acknowledge a very simple reality: To provide basic services like banking and credit to the poor — and to do so ethically and humanely — will require business models that can operate without profit, or even at a loss.

One proposal that's been shopped around — and that presidential candidate Bernie Sanders has endorsed — is for the Postal Service to double as a bank to the poor. The U.S. Postal Service's own Inspector General wrote a detailed paper on how the agency could provide basic checking and savings accounts to low-income Americans through its physical postal network. It even describes how the USPS could provide the same kind of small-bore loans as payday lenders, but on vastly more forgiving terms and with far lower interest rates. Think of it as a "public option" for banking and lending.

The irony, of course, is that the Postal Service is itself already threatened by providing services to the poor. Private mail companies like FedEx do not serve low-income areas precisely because it isn't profitable to do so. Politicians complain the Postal Service can't pay its own bills (though that's mainly thanks to deliberate sabotage) and thus want to shut it down. But low-income communities can only be served at a loss, which is why the Postal Service relies on subsidies from other parts of the government. It's almost baked into the math. We don't extend mail services to the poor because it makes business sense to do so; we do it because it's morally right.

So why not extend the same ethics to banking and credit?

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.