The ethics behind facial recognition vans and policing

The government is rolling out more live facial recognition technology across England

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

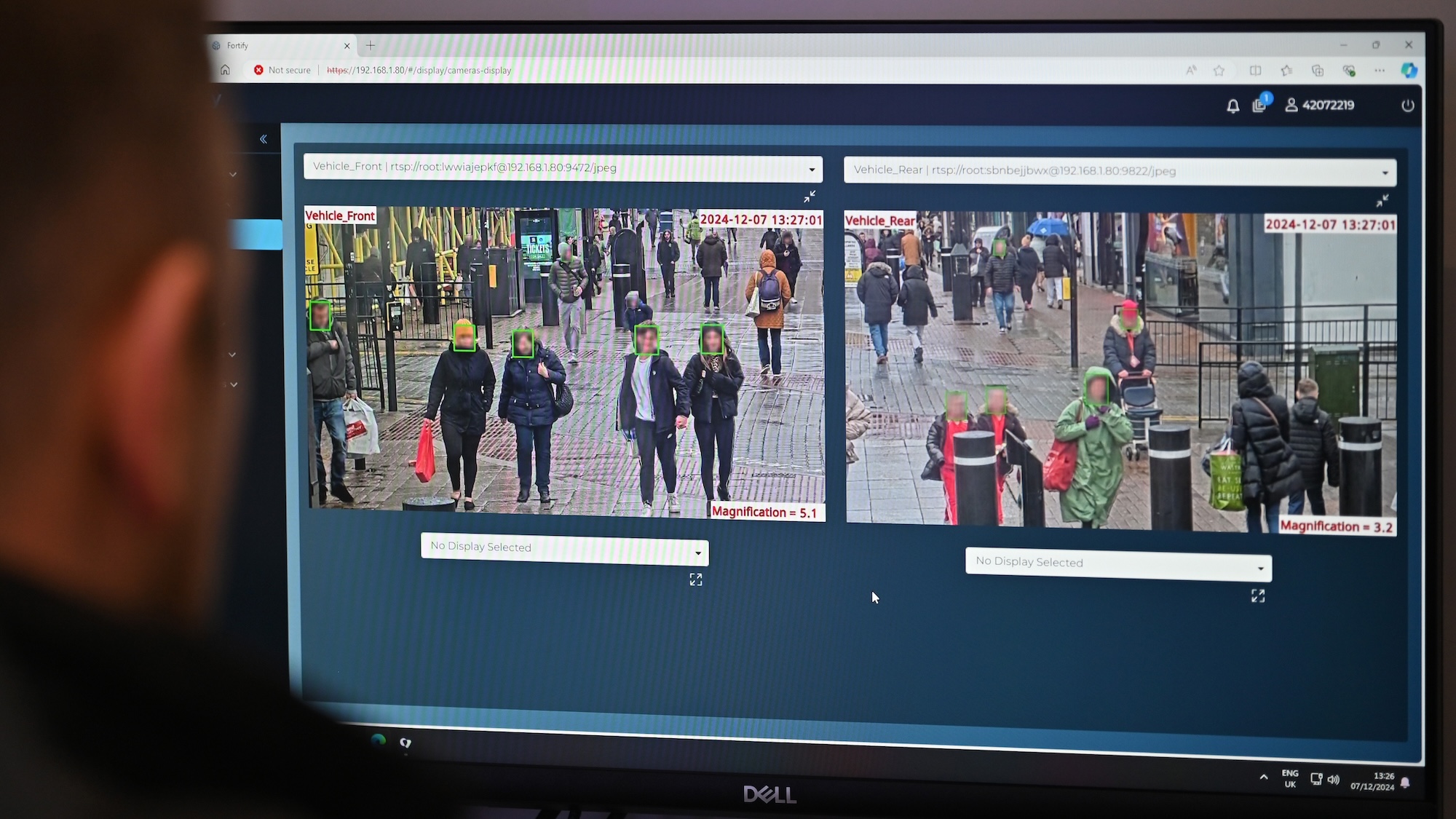

The government will equip seven police forces in England with new live facial recognition (LFR) vans in a bid to trace suspects of serious crimes, including murder and sexual assaults, more effectively.

The Home Office announced that it would give the forces shared access to 10 new vans, which can scan the faces of people passing by and match them against a database of suspects. Home Secretary Yvette Cooper said the technology will be used in a "targeted way" and has so far been responsible for hundreds of arrests in London, where it has already been deployed.

However, LFR has been strongly criticised by civil liberties groups for the potential to invade privacy. The Big Brother Watch campaign group said the "significant expansion of the surveillance state" was "alarming".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How does LFR work?

Specially trained officers staff the vans, which are usually posted at busy public spaces. Cameras then scan the faces of people nearby in real-time, taking measurements of facial features such as the distance between the eyes, and the length of the jawline to establish a set of unique biometric data.

The data is automatically compared to a watchlist of suspects by the technology, which then flags to officers any potential matches and enables them to approach the possible suspect.

Changes to the Investigatory Powers Act last year also now allow the use of artificial intelligence to scan data "when there is no expectation of privacy", said The Economist.

Does it work?

Government and police figures suggest that LFR has been extremely effective in identifying criminals. According to data released in July, the Metropolitan Police said it had "made 1,000 arrests using live facial recognition to date, of which 773 had led to a charge or caution", said The Guardian. However, that number accounts for "just 0.15% of the total arrests in London since 2020", said The Register.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The government cited figures from the past year, suggesting police in London had made "580 arrests in 12 months, including 52 registered sex offenders who breached their conditions", said the BBC.

Critics, though, say this comes at a cost, with a deep invasion of the privacy of innocent people who have their faces scanned.

Where will it be used?

Up until now, only London and South Wales police have had access to permanent LFR technology, but almost all police forces use retrospective facial recognition, in which officers use CCTV or social media images of suspects to compare against the database. Likewise, some police use operator-initiated facial recognition, which is used to scan the faces of people of specific interest.

The Home Office announcement means seven more forces across England, comprising Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, Bedfordshire, Surrey, Sussex, Thames Valley and Hampshire, will now share access to the 10 new vans and be able to obtain the live technology.

There is little official guidance on where and when LFR can be used, leaving it down to police discretion to deploy the technology in public spaces.

What are the ethical concerns?

The biggest ethical concerns over LFR include invasion of privacy, a lack of regulation, and accuracy.

The majority of people scanned by LFR will be innocent, but will be tracked by the technology whether they choose to or not. A poll by the Centre for Emerging Technology and Security and the Alan Turing Institute this year found that "60% of Britons are comfortable" with the police using LFR in a crowd, said The Economist.

Its accuracy has also been called into question. The Met says there have been just seven false alerts so far in 2025, but there have been notable cases in which innocent people have been questioned after being falsely identified by the system. One man, Shaun Thompson, is taking the Met to the High Court, having been wrongly identified and stopped last year.

Campaigners also say there is a lack of regulation and oversight around the surveillance powers as use increases. For instance, police are "free to employ any AI tools they like" while using LFR, which means it is "impossible to know where and how they are being used", said The Economist. Critics say that could lead to systems recognising some types of faces better than others, and lead to greater discrimination against certain groups.

Richard Windsor is a freelance writer for The Week Digital. He began his journalism career writing about politics and sport while studying at the University of Southampton. He then worked across various football publications before specialising in cycling for almost nine years, covering major races including the Tour de France and interviewing some of the sport’s top riders. He led Cycling Weekly’s digital platforms as editor for seven of those years, helping to transform the publication into the UK’s largest cycling website. He now works as a freelance writer, editor and consultant.

-

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics

-

How the ‘British FBI’ will work

How the ‘British FBI’ will workThe Explainer New National Police Service to focus on fighting terrorism, fraud and organised crime, freeing up local forces to tackle everyday offences

-

‘Stakeknife’: MI5’s man inside the IRA

‘Stakeknife’: MI5’s man inside the IRAThe Explainer Freddie Scappaticci, implicated in 14 murders and 15 abductions during the Troubles, ‘probably cost more lives than he saved’, investigation claims

-

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shooting

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shootingSpeed Read Police did not share the identities of the officers or the slain suspect, nor the motive or the focus of the still-active investigation

-

Dash: the UK's 'flawed' domestic violence tool

Dash: the UK's 'flawed' domestic violence toolThe Explainer Risk-assessment checklist relied on by police and social services deemed unfit for frontline use

-

What to do if your phone is stolen

What to do if your phone is stolenThe Explainer An average of 180 phones is stolen every day in London, the 'phone-snatching capital of Europe'

-

The Met police's stop and search overhaul

The Met police's stop and search overhaulThe Explainer More than 8,500 Londoners have helped put together a new charter for the controversial practice

-

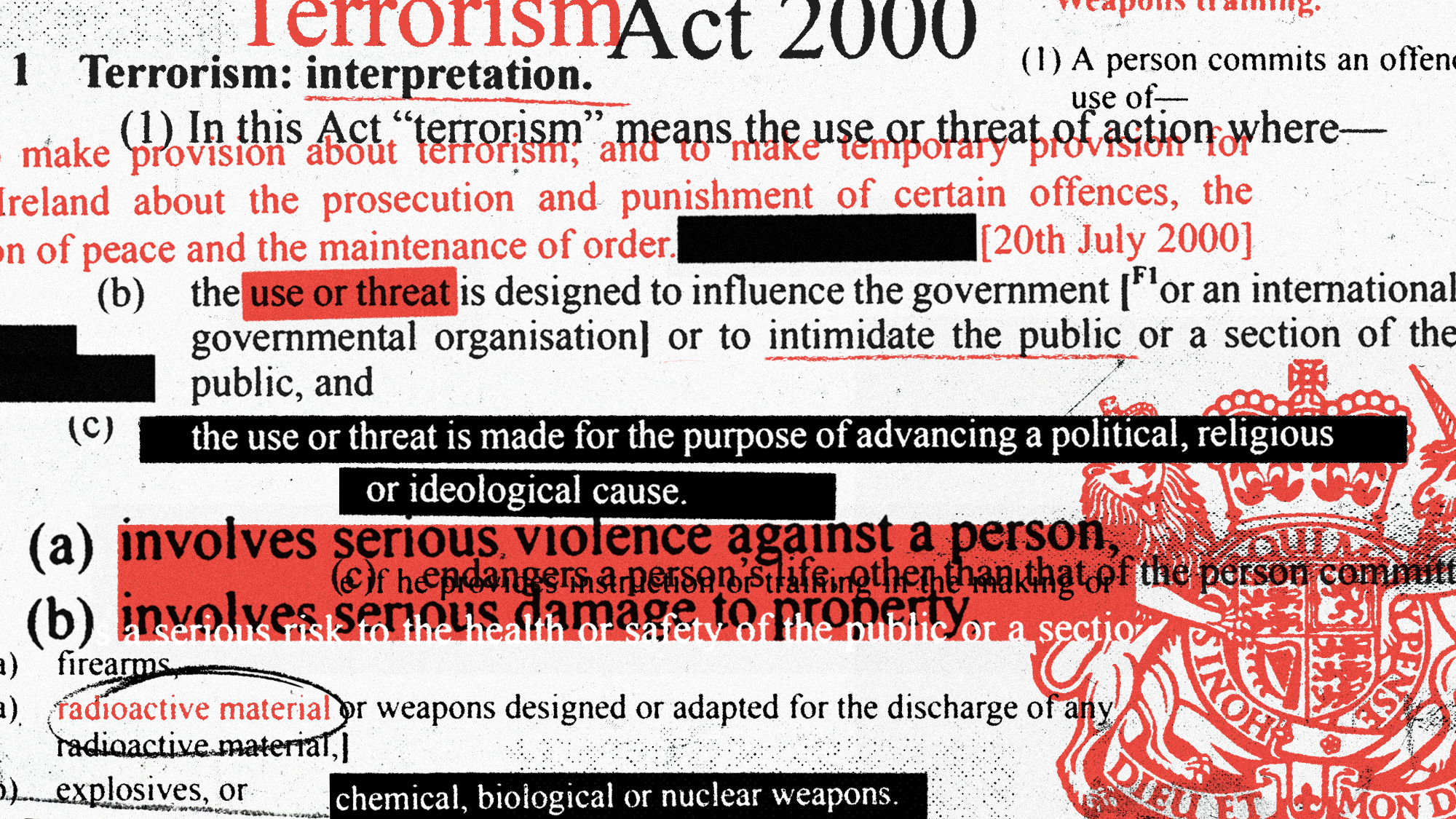

How should we define extremism and terrorism?

How should we define extremism and terrorism?Today's Big Question The government has faced calls to expand the definition of terrorism in the wake of Southport murders