Dash: the UK's 'flawed' domestic violence tool

Risk-assessment checklist relied on by police and social services deemed unfit for frontline use

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The UK's safeguarding minister has called for an overhaul of the main tool used to decide if a domestic abuse victim needs urgent support.

Jess Phillips told the BBC's File on 4 that the current Dash assessment "doesn't work", amid mounting evidence that it fails to correctly identify those at the highest risk of further harm.

Violence against women and girls accounts for 20% of all recorded crime in England and Wales, according to the National Police Chiefs' Council. A woman is killed by a man every three days in the UK; in the year to March 2024, there were 108 domestic homicides in England and Wales, according to the Office for National Statistics.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How does Dash work?

The Dash (Domestic, Abuse, Stalking, Harassment and Honour-Based Violence) assessment is a checklist, co-developed by domestic-abuse charity SafeLives. It features 27 mainly yes or no questions put to victims – including "Is the abuse getting worse?" and "Has the current incident resulted in injury?"

The victim's answers produce a score that's meant to determine their risk of imminent harm or death. Answering "yes" to at least 14 questions classes a victim as "high risk" and guarantees intensive support and urgent protection. No specialist support is guaranteed to anyone who gets a "medium" or "standard" risk score.

Since 2009, the Dash risk scores have been relied on by many police forces, social services and healthcare workers to determine what action is taken after a reported incident, although practitioners are encouraged to use their "professional judgement" to override low scores or to escalate a case if there are multiple police callouts in a year.

What's wrong with it?

Academics, domestic abuse charities and bereaved families have long raised doubts over the accuracy of the Dash assessment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As far back as 2016, the College of Policing review found "inconsistencies" in Dash, and recommended a different tool for frontline police responders. And in 2020, a London School of Economics study of Greater Manchester Police data found that, in nearly nine out of ten repeat cases of violence, the victim had been classed as standard or medium risk by Dash.

In 2022, an analysis by researchers from the Universities of Manchester and Seville found that the Dash questions "contributed almost nothing" to its performance as a predictive tool, and, earlier this month, an investigation by The Telegraph identified at least 55 women who had been killed by their partner after being graded only standard or medium risk.

"Too many have died without help, as the Dash system failed to recognise the true threat they faced," said Alicia Kearns MP, the shadow safeguarding minister.

Pauline Jones, the mother of Bethany Fields, who was killed by her partner in 2019, a month after being graded a medium risk by Dash, put it more directly: "When you hear about the Dash, and you know your daughter's death was so easily preventable, it destroys not just your heart, but your very soul.”

Is there a better option?

Dash has "obvious problems", said Phillips. She is reviewing the entire system but "until I can replace it with something" that works better, "we have to make the very best of the system that we have." Any risk assessment tool is "only as good as the person who is using it".

Some police forces have adopted Dara, the tool that the College of Policing has developed, instead of Dash. Other forces and organisations, in the UK and abroad, are calling for a more radical overhaul, using using new technology to assess future risk. "In certain contexts," said Forbes, "AI-enabled tools are making it easier to discreetly gather evidence, assess personal risk and document abuse – actions that were previously unsafe or more difficult to carry out."

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics

-

How the ‘British FBI’ will work

How the ‘British FBI’ will workThe Explainer New National Police Service to focus on fighting terrorism, fraud and organised crime, freeing up local forces to tackle everyday offences

-

‘Stakeknife’: MI5’s man inside the IRA

‘Stakeknife’: MI5’s man inside the IRAThe Explainer Freddie Scappaticci, implicated in 14 murders and 15 abductions during the Troubles, ‘probably cost more lives than he saved’, investigation claims

-

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shooting

3 officers killed in Pennsylvania shootingSpeed Read Police did not share the identities of the officers or the slain suspect, nor the motive or the focus of the still-active investigation

-

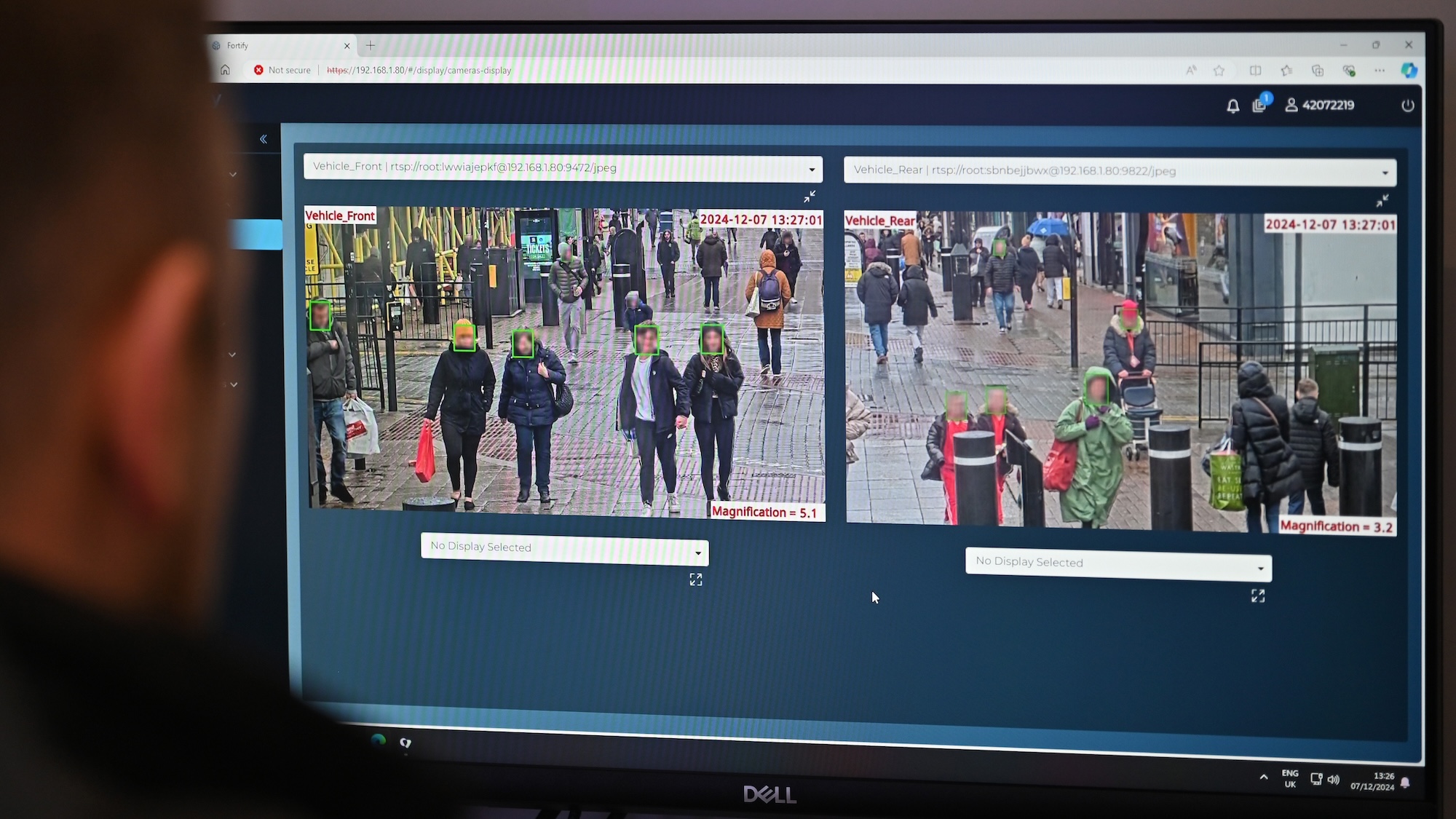

The ethics behind facial recognition vans and policing

The ethics behind facial recognition vans and policingThe Explainer The government is rolling out more live facial recognition technology across England

-

What to do if your phone is stolen

What to do if your phone is stolenThe Explainer An average of 180 phones is stolen every day in London, the 'phone-snatching capital of Europe'

-

The Met police's stop and search overhaul

The Met police's stop and search overhaulThe Explainer More than 8,500 Londoners have helped put together a new charter for the controversial practice

-

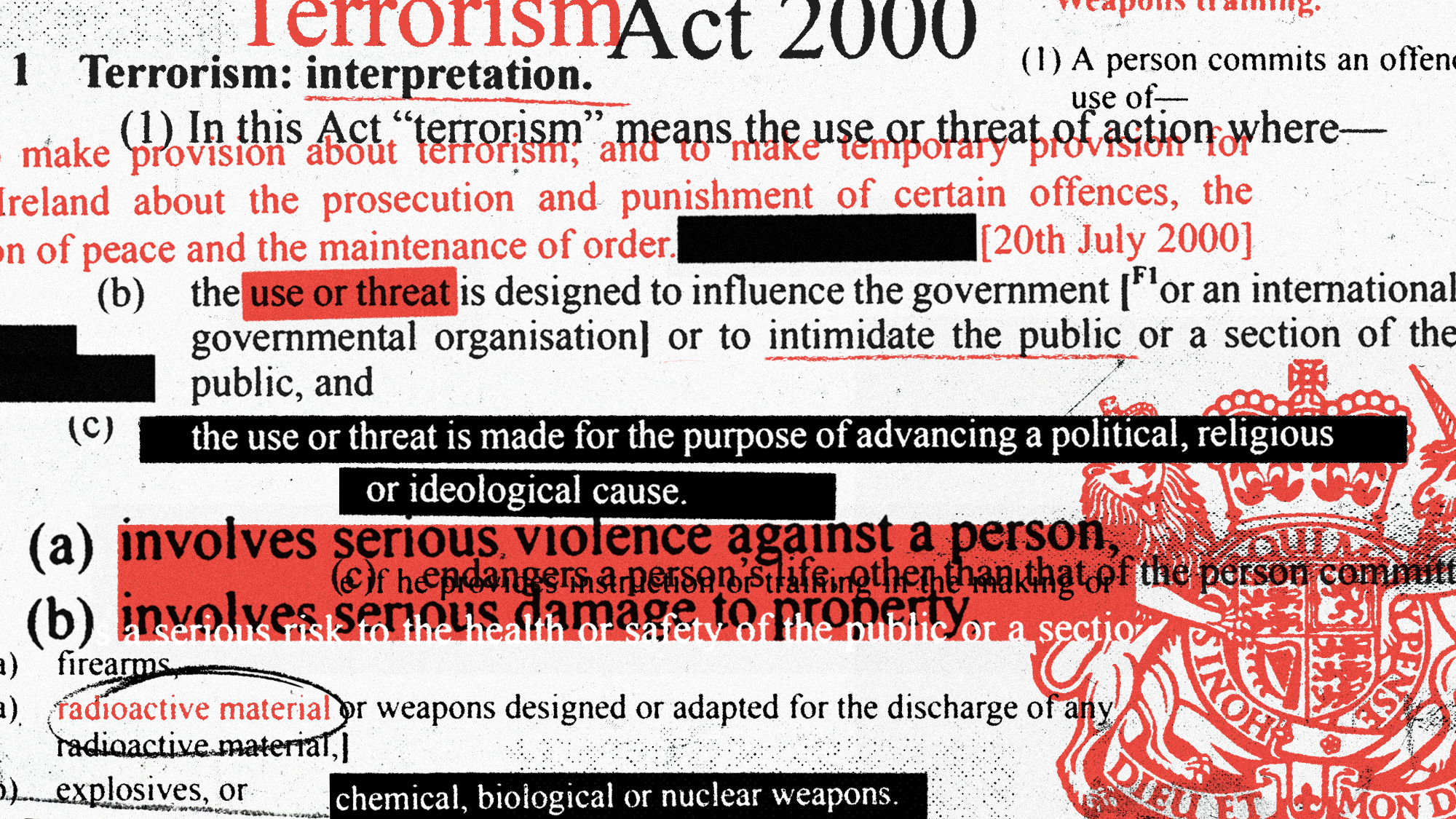

How should we define extremism and terrorism?

How should we define extremism and terrorism?Today's Big Question The government has faced calls to expand the definition of terrorism in the wake of Southport murders