The price of an Olympic moment

There is something at the Olympics greater than gold

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What is the price of an Olympic moment? When the Rio Games' opening ceremonies began, we all understood the contract we were entering into: hours of boredom and gobs of mind-melting advertising in exchange for a few seconds, here and there, of shock and joy. The Olympics, in this way, are a lot like life. We have to take in the banal, the pointless, and the painful in order to savor a few moments of triumph.

This is the contract we abide by, and the price we pay. Host cities pay an even higher price, and athletes the highest of all. The deal they make, in theory, is a lifetime of sacrifice and dedication in exchange for a bright charm. Worth wondering is how many athletes arrive at the Games hoping to win not a medal, but a moment.

The Olympic moment doesn't always play by the rules. In the Calgary Olympics of 1988, the figure skating rivalry between American Debi Thomas and East German Katarina Witt — called "The Battle of the Carmens," because both had set their programs to Bizet's opera, the skating equivalent of showing up to a party in the same dress — was all anyone could talk about. No one remembered Canadian skater Elizabeth Manley until she shot onto the ice after Witt's staid, careful performance, a force of sheer exuberance in a night dedicated to steely competition. Viewers thought the best thing the night could possibly yield was a tense battle of will. They were wrong. "Wouldn't it be great if every human being could have a moment like this once in their lives?" Jim McKay said as the crowd roared and roared. She didn't win the gold, but she won the moment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When it comes to the Olympic moments count, it's hard to beat Bela Karolyi. Karolyi, who legendarily discovered Nadia Comaneci in a Romanian schoolyard and coached her to the first perfect 10 ever awarded to a female gymnast, at the 1976 Games, has been a presence for four decades in a sport whose participants can count themselves lucky if they remain in competition for four years. After the Romanian team's victory served as the highlight of the Montreal Olympics and made 14-year-old Comaneci a global sensation ("SHE'S PERFECT," the cover of Time magazine announced, "But the Olympics Are in Trouble"), Karolyi defected to the United States, and helped make Mary Lou Retton the star of the 1984 Games in the same way Comaneci had been Montreal's star. Nadia Comaneci's Olympic moment came with her first perfect 10; Mary Lou Retton's Olympic moment came when she prepared to execute a vault with the knowledge that anything less than a perfect 10 meant losing the gold.

The networks cameras focused on Retton and Karolyi as he psyched her up before the vault. ("Panda, Panda, Panda!" he chanted, using his pet name for her.) Karolyi's English was broken, but he didn't need to say much to prepare Retton for the apparatus. They were beyond the level of strategy, of complex reassurance. Karolyi only needed to lock eyes with Retton and tell her that she would score a perfect 10 for Retton to go out and do it. So she did.

The relationship between coach and athlete is always in the background of any Olympic event. Sometimes it's visible, sometimes it's not; sometimes we want it to be visible, and sometimes we don't. But the relationships that coaches have with young, female gymnasts — athletes viewers are already primed to see as vulnerable — are often the subject of intense scrutiny, especially when it comes to the question of how often gymnasts are pushed too hard, and forced to endure too much pain, injury, and sacrifice. Even more deeply, the intense relationship between gymnast and coach can suggest a level of control that is not just physical but mental: not just you can but you will.

American viewers' perception of Bela Karolyi has an interesting way of changing from moment to moment: He troubled us when he was the subject of exposés like Joan Ryan's Little Girls in Pretty Boxes, and he inspired us when his athletes vaulted into the kinds of victories we couldn't imagine any other coach producing. Loud, ursine, and inevitably towering over any gymnast he coached, his manner could be read as terrifying in one moment and effervescent in the next, often depending on what perspective you took (and whether the Americans were performing well that night). His ability to unlock his athletes' potential — and to help them reach the crowning moment of the Games — was undeniable. He told them what they could do, and they believed him completely enough to believe him when he told them they were capable of the impossible. Then they did it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The lingering question this dynamic leads us to is whether an athlete can reach the same heights of strength and self-knowledge on their own — whether they can believe themselves capable of doing the impossible without forming such an intense bond with such a dominant figure. It's hard to arrive at an answer to this question. What seems far more readily apparent is the fact that we really don't want to know. Nowhere is this more clear than in one of the greatest Olympic moments in the Games' modern history: Kerri Strug's legendary vault in 1996.

Kerri Strug injured her ankle while landing the first of her two vaults in the women's team final, and limped visibly as she prepared for the second. Tension filled the arena: Could she vault again? The scores were close; the team medal seemed to hang in the balance. If Kerri Strug herself had any doubts about whether she would finish the competition, however, they were immediately dispelled by Bela Karolyi. "You can do it," he called to her. He had little idea of how severely she had been injured, and no way of knowing how much pain she was in. Those questions didn't matter. "You can do it," he repeated. "You can do it. You can do it. Kerri, you can do it. Don't worry." So Kerri did.

At the time, media outlets and Olympic commentators would make the near-universal claim that Kerri's Olympic moment was so miraculous because she had landed her vault on one leg. She didn't. She landed on two legs, subjecting her injured ankle to the full force of another vault, and then immediately retracted one foot, collapsing onto the mat.

"Kerri Strug is hurt! She is hurt badly!" the NBC commentator announced, sounding almost as shocked as the crowd. "Probably the last thing she should have done was vault again, and now she is in a lot of pain." Karolyi picked her up and carried her to the podium. We had our Olympic moment, but the questions it inspired were too troubling to ask, so we swore we saw something that had never occurred: a gymnast landing a vault on one foot, getting the glory without the pain, making sacrifices without sacrificing her power to choose, having it both ways.

Of all the attributes that make the Olympic moment, this might be the most defining: that we can lift it out of context and ignore its inevitable cost, and avoid even asking what that cost might be.

Sarah Marshall's writings on gender, crime, and scandal have appeared in The Believer, The New Republic, Fusion, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2015, among other publications. She tweets @remember_Sarah.

-

Political cartoons for February 6

Political cartoons for February 6Cartoons Friday’s political cartoons include Washington Post layoffs, no surprises, and more

-

Trump links funding to name on Penn Station

Trump links funding to name on Penn StationSpeed Read Trump “can restart the funding with a snap of his fingers,” a Schumer insider said

-

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty ends

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty endsSpeed Read New START was the last remaining nuclear arms treaty between the countries

-

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.The Explainer The big game will showcase a variety of savvy — or cynical? — pandemic PR strategies

-

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.The Explainer How to make sense of the Boston massacre

-

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIII

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIIIThe Explainer Most boring Super Bowl ... ever?

-

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio State

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio StateThe Explainer I and millions of other people in these two cold post-industrial states would not miss The Game for anything this side of heaven

-

When sports teams fleece taxpayers

When sports teams fleece taxpayersThe Explainer Do taxpayers benefit from spending billions to subsidize sports stadiums? The data suggests otherwise.

-

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseball

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseballThe Explainer Boston and L.A.? This stinks.

-

This World Series is all about the managers

This World Series is all about the managersThe Explainer Baseball's top minds face off

-

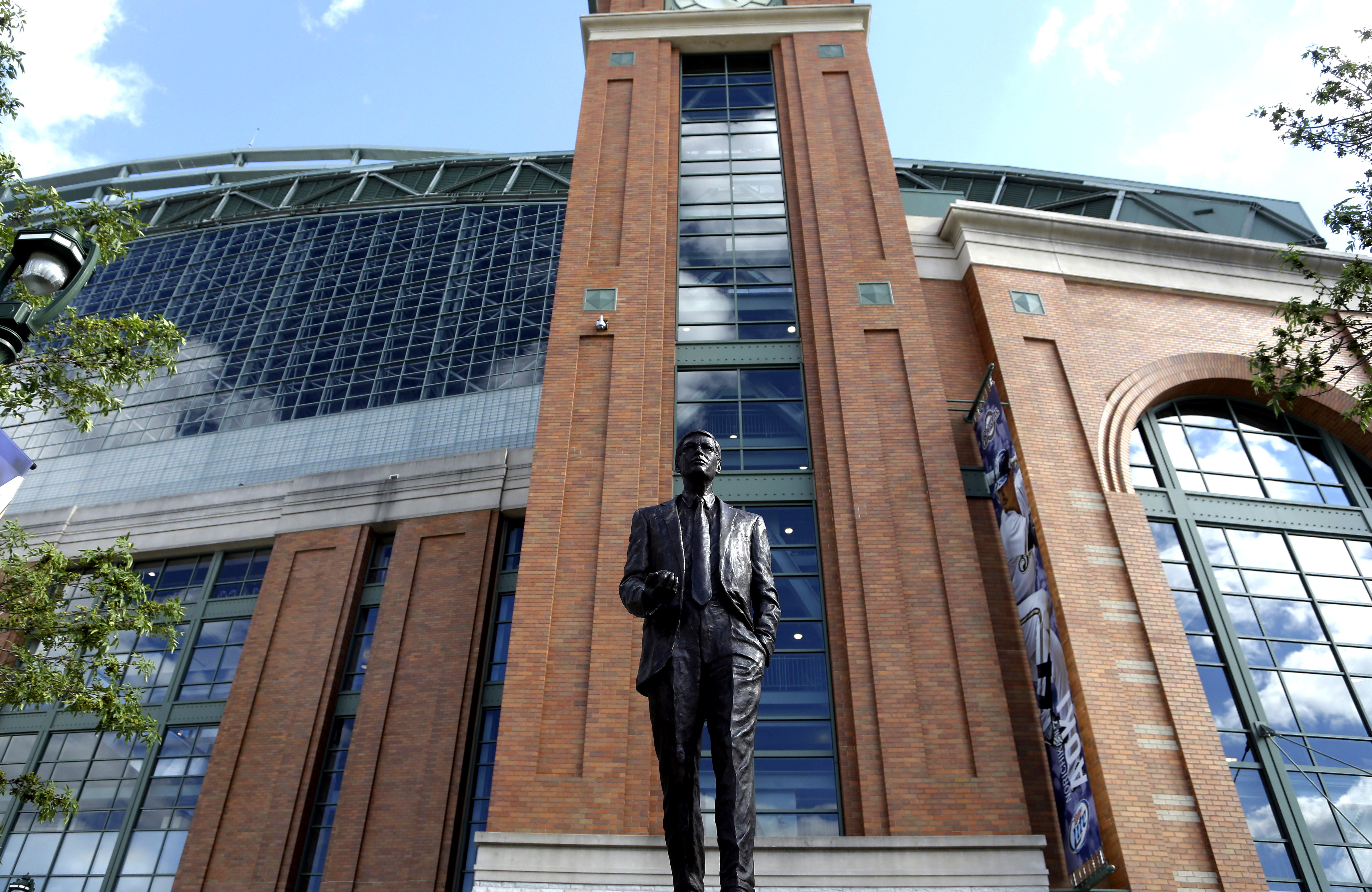

Behold, the Bud Selig experience

Behold, the Bud Selig experienceThe Explainer I visited "The Selig Experience" and all I got was this stupid 3D Bud Selig hologram