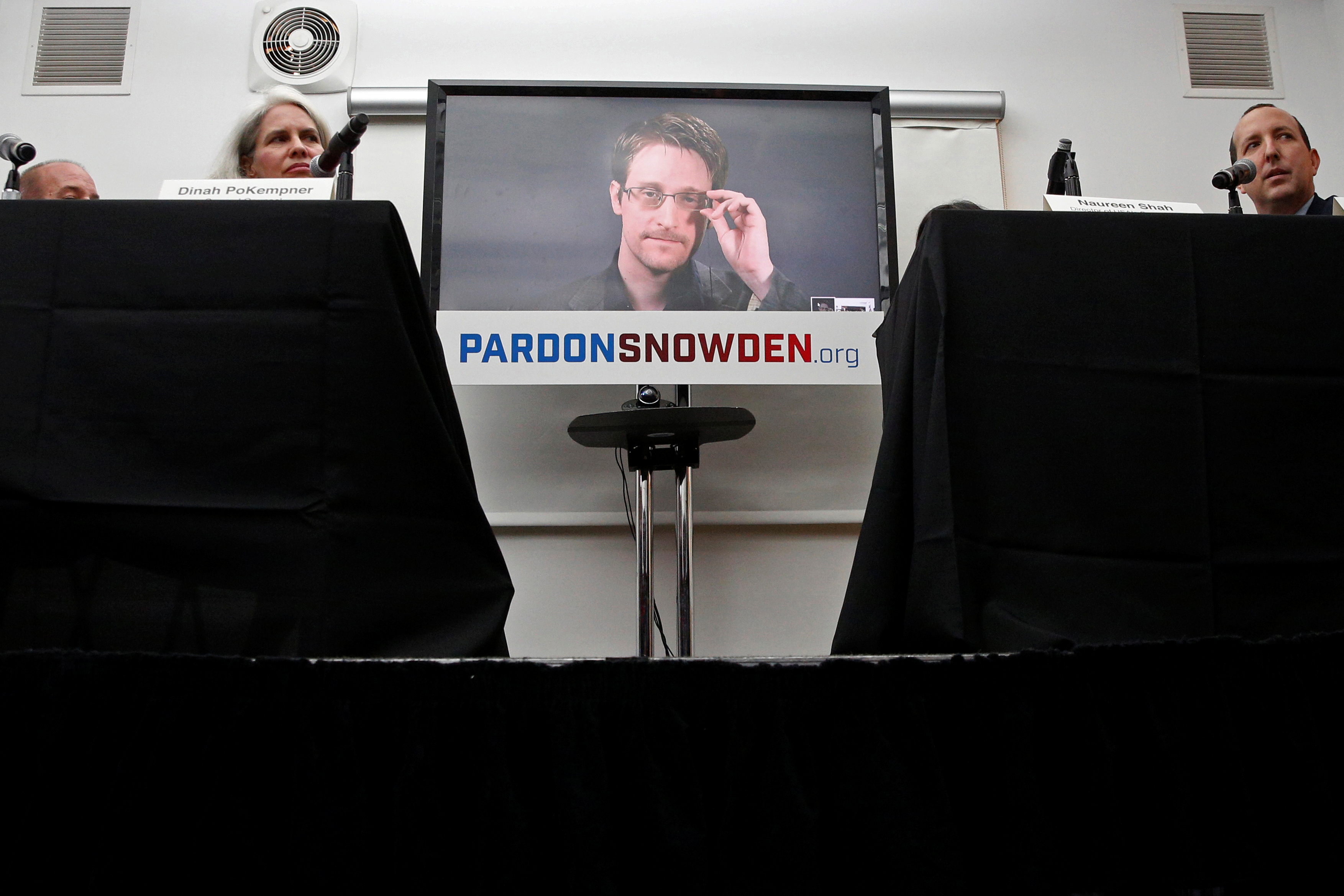

The case against Snowden

Edward Snowden isn't a hero. He's a criminal — and a reckless megalomaniac.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When was the election that placed Edward Snowden in the exalted position of Higher Guardian of the American People? I, for one, don't remember voting in such a contest. But there must have been one, and Snowden must have won it handily, since otherwise the arguments being marshaled in favor of pardoning him for leaking a mountain of classified information to journalists, who promptly published a large portion of it, make no sense at all.

You see, the United States has a set of political institutions empowered to, among other things, defend the nation's common good. Defending the common good requires espionage and other forms of state secrecy. In the post-9/11 world — a world in which we know that terrorists, acting independently from governments, will do everything in their power to inflict maximum, indiscriminate harm on the United States and its citizens — defending the common good will require a degree of domestic as well as foreign surveillance.

In the months and years following the 9/11 attacks, the United States developed secret anti-terror programs for domestic and foreign surveillance. Edward Snowden learned considerable details about these programs while working in a series of posts for the CIA and as a subcontractor for Dell and Booz Allen Hamilton. And then he decided that, in his role as Higher Guardian of the American People, he would break laws, oaths, and contractual obligations in order to make this information public. He made this decision all by himself, which is precisely what we must have had in mind when we empowered him to exercise that judgment on our behalf. No wonder so many consider him a hero.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Oh wait, what's that you're saying? He wasn't elected to such a position, and no one formerly appointed him to it? Well, then that must mean that he just made the call all on his own — that he just decided, on his own authority, that he, and not the president of the United States or the CIA director or the chairman of the Joint Chiefs or the heads of the Senate or House Intelligence Committees, would be the one to determine what should be secret and what should be public, what should be classified and what should be revealed for all the world to see and know.

If that sounds rather lawless, not to mention a little megalomaniacal, that's because it is. The United States has laws, and Edward Snowden broke them. Many of them. He should be tried and face potential punishment for his actions.

"But no!" cry his defenders. "Snowden is a hero, a whistleblower, who risked everything to ensure government transparency! We owe him a presidential 'Get Out of Jail Free' card in the form of a pardon!"

There are just two problems: Snowden isn't a whistleblower, and the virtues of transparency are overblown.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The problem with describing Snowden as a whistleblower is that the metaphor doesn't apply in his case. A whistleblower is someone who discovers unlawful activity taking place in a private firm or public agency and "blows a whistle," bringing that unlawful activity to the attention of the legal authorities who can then prosecute the perpetrators to stop them from engaging in covert criminality.

But the National Security Agency was not behaving criminally in running surveillance and compiling "metadata" about telephone and computer users. It was doing what the democratically elected Congress and president had empowered it to do: striving to keep the country safe from Islamic terrorism.

If the NSA had been recording and preserving random conversations or the content of random emails and text messages, that might have raised legitimate First Amendment concerns. But metadata is just that: meta. It's billions of bits of information: This phone number called that phone number; that IP address visited this IP address — multiplied hundreds of millions of times. It's essentially useless unless someone is given something to look for.

Say a cell phone is found after the bombing of a terrorist training camp in Afghanistan and the phone's call record shows that it dialed a number in Alexandria, Virginia, several times in recent weeks. Then the metadata becomes useful: Where exactly is the phone in the Washington suburbs? Where was the phone at the time of the calls from Afghanistan? What other numbers have been called by that phone in Virginia? Where are those phones located? At that point a judge at a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court might be asked to authorize the monitoring, capturing, and analyzing of actual (non-meta) data or content (including voice conversations, emails, and text messages) of the people connected to that cell phone found in a terrorist training camp in Afghanistan.

That, among much else, is what Snowden took it upon himself to reveal and expose. Because he decided, all on his own, that such a program should not be kept secret, that it should be made public.

"But we should thank him!" say his champions. "Congress intervened after the Snowden leaks to change the way such metadata is handled by the NSA and the private companies that were originally tasked with gathering it. That proves he was right!"

No, it doesn't. It proves only that once the program was publicized, lawmakers felt the need to make an adjustment to how it was run. It was Snowden, in a monumental, reckless act of self-aggrandizement, who single-handedly decided that the program deserved to be publicized in the first place.

That decision wasn't his to make.

"But what about transparency?" respond the Snowden-flakes. "It's obviously always better for the public to know precisely what the government is doing, and how, and to whom."

Sorry, but this isn't obvious at all. As Jonathan Rauch recently argued for The Atlantic in what may be the most important essay of the political season, the relentless drive for transparency in the name of good government over the past half century may have had the unintended consequence of making good, or even functional, government close to impossible.

Though unthinkable to many, the reality may be that democratic politics functions better in twilight and shadows than it does in the blinding glare of the media's klieg lights.

If that's arguably the case in general, it's indisputably true when it comes to espionage, including selective domestic surveillance. A program to ensure that the nation avoids getting caught once again with its pants down, as it did on 9/11, will work best if its details, and even its existence, are not publicly known. "Oh, the U.S. government can do that? Well, then we better change our plans to avoid detection": When people plotting political violence say those words, the men and women entrusted with our nation's safety are stymied in their work. It really is that simple.

Snowden's defenders like to talk about democracy and accountability. But it's neither democratic nor accountable to elevate oneself into an authority above all others, act unilaterally in defiance of the law, and then flee the country to avoid facing the consequences. That's precisely what Snowden did. He should return to the United States to face the legal ramifications of his actions — or spend the rest of his days on the run.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonadeTODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreat

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreatIn the Spotlight Several cities are reportedly on ICE’s list for immigration crackdowns

-

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day