Iggy Pop is a work of modern art

Iggy Pop is the creation of James Osterberg, a trailer-dwelling teenager from Michigan who hated the commercialism of music made in corporate committee meetings

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

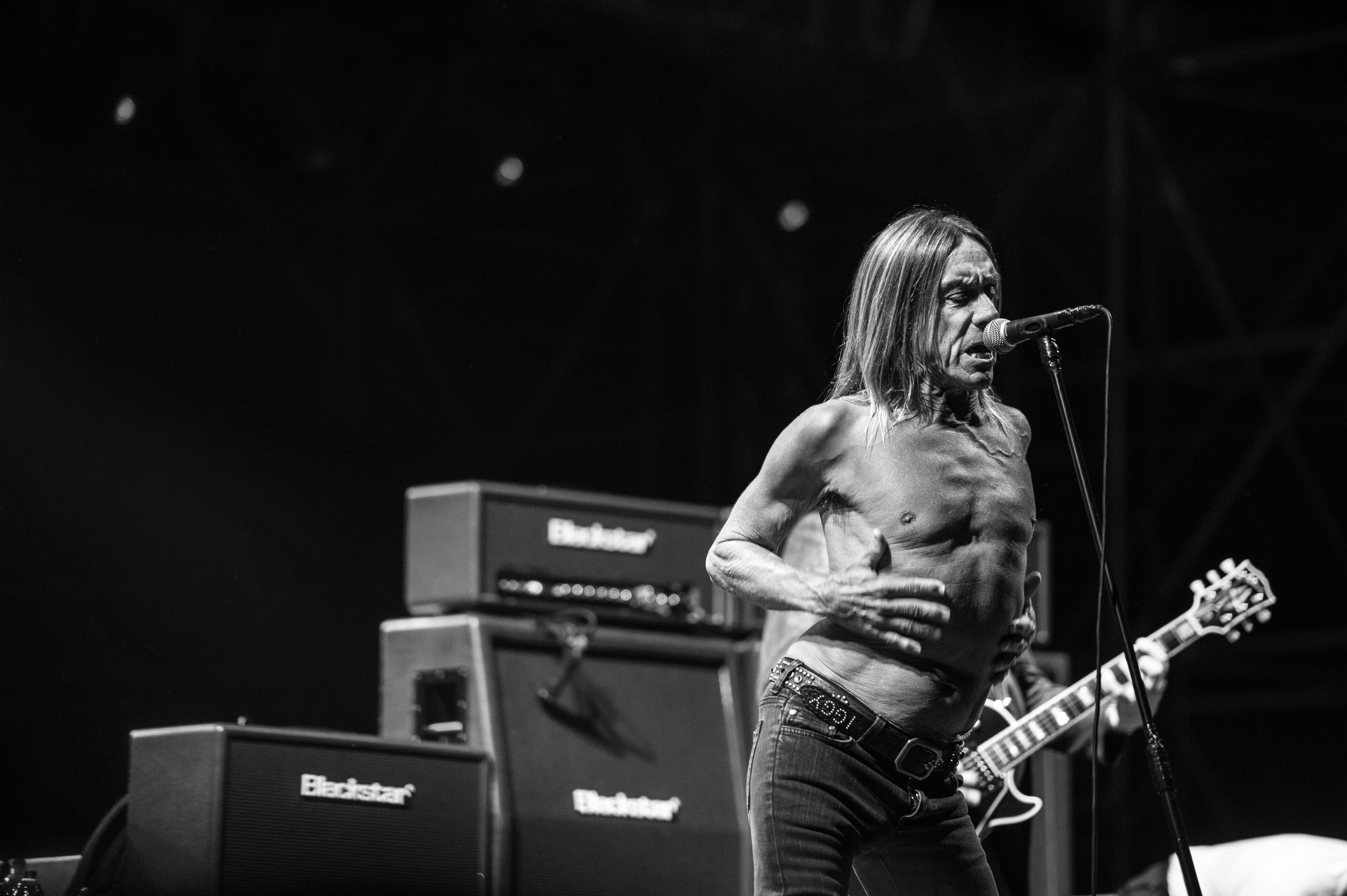

Iggy Pop is rock music's great work of modern art. He channels an eclectic array of inspirations, including Harry Partch, Miles Davis, and Soupy Sales, whose "25 words or less" fan letter policy influenced Pop's terse lyricism. The way Pop moves, the way he contorts his torso, the orgasmic grimace twisting his face — it's as if a gale is struggling to escape that veiny enshrinement he calls a body. He barrels across the stage, bellowing in his ravenous, salacious wail. His fervor and ferocity, rooted in blues and jazz but imbued with the mania of a then-unidentified genre that would become punk, bring to mind an Ezra Pound quote: "The image is more than an idea. It is a vortex or cluster of fused ideas and is endowed with energy."

Iggy Pop is the creation of James Osterberg, a trailer-dwelling teenager from Michigan who hated the commercialism of music made in corporate committee meetings. He cut some tracks as the drummer for a milquetoast band called The Iguanas, but, beguiled by the on-stage affectations of Jim Morrison, he switched from drums to vocals, losing his shirt in the process. He formed the proto-punk band The Stooges in the late '60s, for whom he performed, at various times, vocals, drums, and vacuum cleaner. He embodies the mythos of a rock frontman, all the liquor and drugs and physical/mental/emotional abuse that such a life entails. Even he seems sort of amazed by his continued existence.

Gimme Danger, Jim Jarmusch's new documentary on The Stooges (playing at the New York Film Festival), examines the history and histrionics of Iggy Pop and his cohort. More than any previous exegesis of the seminal band, it depicts Pop as a physical force — a body artist. Jarmusch, one of the essential American filmmakers of the last 30 years, is a bravado stylist whose best films (Stranger Than Paradise, Dead Man, Only Lovers Left Alive) bask in the poetry of unhurried malaise, but he doesn't have quite the same deft grasp on documentary. The inherent restrictions of nonfiction seem to confine him slightly, like a pair of too-tight jeans, and the film feels oddly tame, considering the antics of the band in question. It doesn't really matter, though, because he has the most entertaining talking head imaginable in Iggy Pop, with whom Jarmusch is real-life friends, and their mutual passion permeates the movie.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Pop returns, again and again, to the idea of artistic singularity throughout the film, as if spiraling around a root note. "I don't want to be punk," he says. "I just want to be." You can hear it on The Stooges' records, the way he barks at the mic instead of singing into it; you can see it on the album cover of The Stooges' Funhouse, that oneiric whorl of fire and flesh, from which Pop seems to be conjured; and, if you were in the front row of any Stooges show, you could feel it, too, all that sweat spraying you in the face, the blood running down his torso in chocolate syrup streaks as he surfed over the wave of bodies in the audience. Pop wanted to create something people had never seen or heard before. In accordance with the musings of Ezra Pound, he made something new, though he didn't quite "make it," as they say — The Stooges were considered failures at the time, at least by the few people who actually heard their records.

But The Stooges, who thrived (briefly) in notoriety before lingering (for years) in obscurity, are now considered one of the most important bands of the 20th century. Guitarists Ron Asheton (who died in 2009) and James Williamson (who spent 27 years working in Silicon Valley after the band broke up) may not have Pop's ubiquitous pop-culture presence, but their influence on guitar rock has been profound. The commingling of jazz and junk, noise and nuance, is what distinguishes The Stooges from those they influenced. They were manicured mania. The rhythm section could ride a groove for five, 10 minutes while Pop dove into the crowd (which didn't catch him), or thrashed around on the floor, as if stricken with a sudden fit of demonic possession.

What other quote-unquote punk band can follow up a track as mercilessly lurid and lean as "TV Eye" with the seven-minute slither of "Dirt"? In that song, Dave Alexander's bass line sways like a drunk looking for a wall to lean on as the guitar cuts and jabs in noisy bursts before segueing into an almost tranquil arpeggio that wouldn't sound out of place on a Smiths' record. Pop, favoring succinct provocations, oozes sleaze like, "And do you feel it? / Said do you feel it when you touch me?" The last two words come in pained/pleasured grunts — "Touch! Me!" before he howls, "Well there's a fire! Well, there's a fireeee!" Cue the torrid guitar solo. The second half of Funhouse, a schizoid ramble of guitar and horn duality, perforated by Pop's barbaric yawp, shares more with Bitches Brew or the albums of Pharoah Sanders than anything The Ramones ever did.

The Stooges were theater, and Iggy Pop a persona, one James Osterberg has inhabited for most of his life. It's a performance as immersive and physical as anything Marlon Brando or Buster Keaton did: His body, all veiny sinew, contoured like a snake conjured by a charmer writhing out of the mire of sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll; the dog collar wrapped around his neck; the peanut butter smeared on his chest; the high-waisted jeans unbuttoned, flaps spilling down like scowling lips. The wiry, wired frontman put on one hell of a show.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Greg Cwik is a writer and editor. His work appears at Vulture, Playboy, Entertainment Weekly, The Believer, The AV Club, and other good places.