Why corporate clawbacks need real claws

This is the true lesson of the scandal at Wells Fargo

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The smartest insight and analysis, from all perspectives, rounded up from around the web:

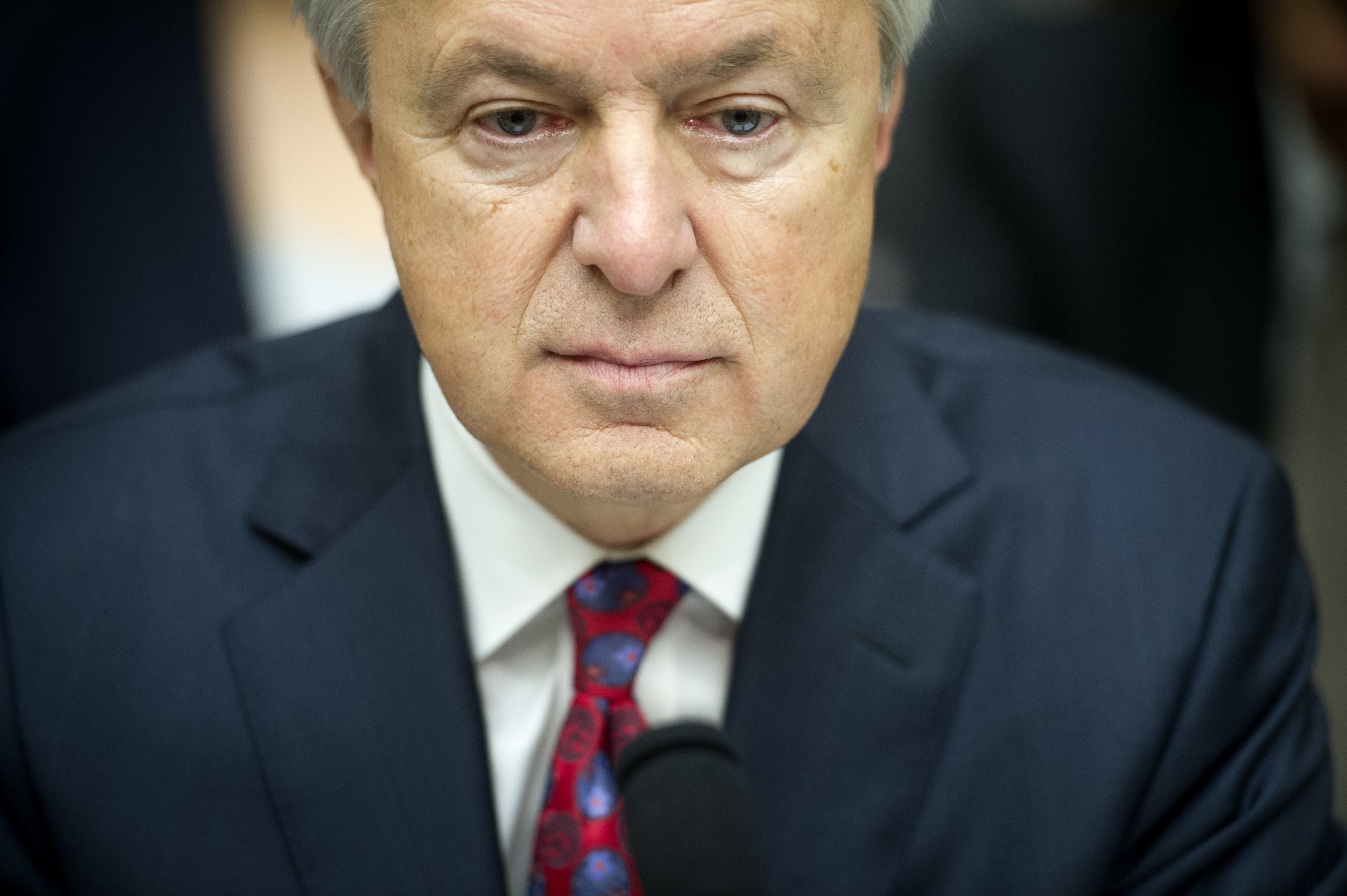

An "unprecedented move" to strip Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf of $41 million in pay "has sent a chill through Wall Street," said Olivia Oran and Ross Kerber at Reuters. The board of the embattled banking giant announced last week that it will "claw back" some of Stumpf's stock awards in the wake of devastating revelations that Wells employees created millions of fake and unauthorized accounts. Since the financial crisis, all of the top U.S. banks have added or strengthened clawback provisions to strip pay from executives who act irresponsibly or take excessive risks. Stumpf, however, is the first CEO of a major U.S. financial firm "to actually have to give back significant pay or benefits as the result of a scandal." With Wells Fargo now under ongoing bipartisan attack in Washington, many in the industry worry that "a hardening political climate" will encourage boards of directors "to be more aggressive about making them forfeit pay."

Historically, clawbacks are extremely rare, said Roger Yu at USA Today. About 80 percent of companies in the S&P 500 have clawback provisions. But because board directors are "generally reluctant to punish their own executives," few companies have actually exercised them. Between 2001 and 2013, 272 companies with clawback provisions restated their earnings — often a sign of corporate negligence or misconduct — but clawbacks were triggered in fewer than 10 cases. Regulators are now hoping to force reluctant corporations' hand. New rules under consideration by the Securities and Exchange Commission would require firms to trigger clawbacks in a wide variety of situations, and for the penalty to apply to executives' pay for seven years instead of three.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"In some respects this seems like too little, too late," said Gillian Tett at the Financial Times. After all, Wells Fargo acted only after Stumpf embarrassed himself in congressional hearings on the phony-accounts scandal, blaming thousands of low-level employees for the widespread wrongdoing. "But tardy or not, historians may end up viewing this clawback as a watershed moment." Carrie Tolstedt, the former head of community banking at Wells Fargo, will also surrender $19 million in stock grants, and both she and Stumpf will give up this year's bonuses. Still, "it is a huge pity that it has taken so long for these reforms to bite." If meaningful compensation forfeiture rules had been firmly in place a decade ago, the scandal at Wells Fargo might never have erupted in the first place. The lesson here: "Clawbacks need claws."

"If the goal is to keep corporate executives honest, compensation clawbacks aren't doing the job," said Gretchen Morgenson at The New York Times. Despite having a clawback policy in place, Wells Fargo waited three years after this accounts scandal first came to light to use it, and only after a storm of negative publicity. Even then, Stumpf's clawback barely left a scratch, said Geoff Colvin at Fortune. Reading the headlines, one "might reasonably suppose that Stumpf would have to write a check for $41 million to return money he'd been paid." Instead, the board's action applied only to unvested stock awards, "meaning he could not yet turn them into money even if he had wanted to." If an executive has to give back compensation, this is about the least painful way to do it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy